Coronavirus energizes the labor movement. Can it last?

In Los Angeles, Glendale and Long Beach, thousands of laid-off janitors and hotel workers besieged elected officials with petitions seeking future job guarantees.

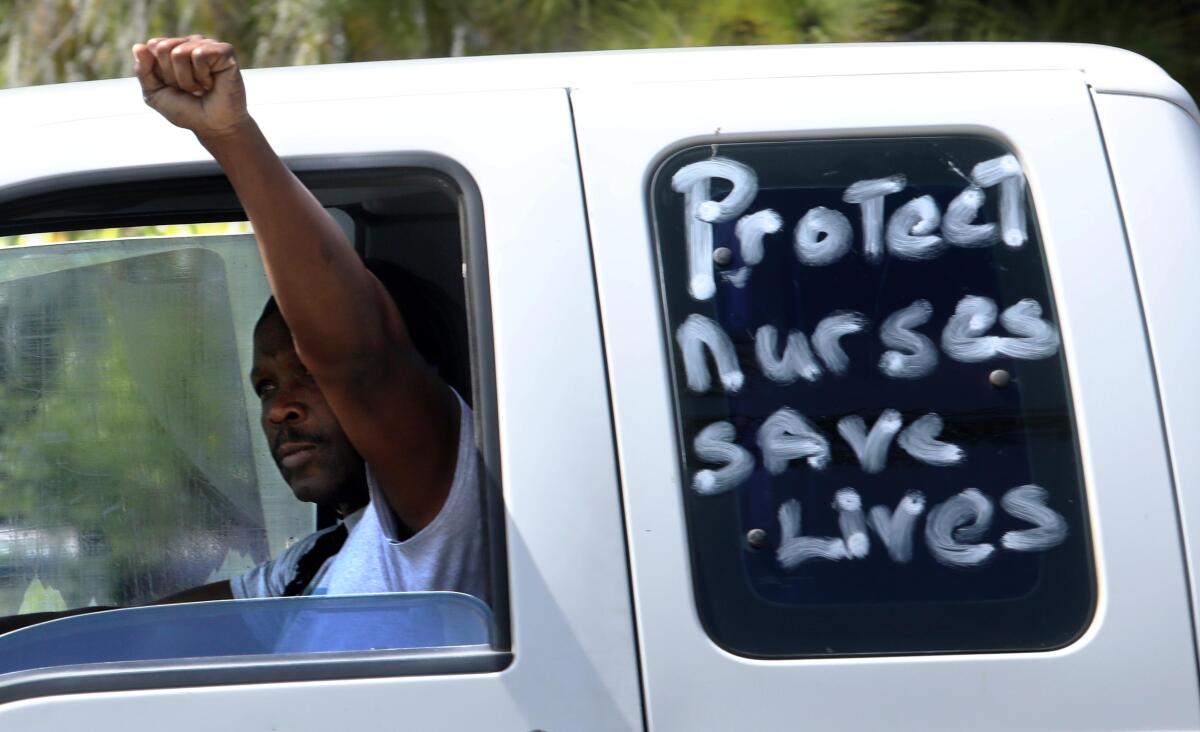

Nurses took to the streets in San Francisco, Santa Monica, Irvine and Oceanside to shame hospitals for failing to protect them against the coronavirus.

And from Oakland to Monterey Park, employees at dozens of fast-food outlets, including McDonald’s, Domino’s and Wendy’s, walked off their jobs protesting a lack of social distancing measures.

The COVID-19 pandemic is unleashing a wave of labor unrest across California and the nation. Unions, harnessing the fear and anger, are organizing many of the protests, rallying media coverage and successfully pressuring public officials, including Gov. Gavin Newsom.

The crisis presents a unique opportunity to press for new business rules on such issues as worker safety, pay and benefits that have long been central to labor’s agenda.

More demonstrations are expected Friday to coincide with May Day, International Workers’ Day. Union nurses at six Los Angeles hospitals will rally for better safety equipment. Car caravans will circle an Amazon delivery hub in Hawthorne and a Ralphs supermarket on Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles — targets of workplace complaints after employees tested positive for the virus.

But as workers flex their muscles, ratcheting up demands on employers, will they open the way to a new era of collective bargaining?

It won’t be easy: Nationally, just 11.6 % of workers are represented by unions. Even in labor-friendly California, the portion has dropped to 16.5% from 22% three decades ago.

“The crisis has laid bare the effects of income inequality and conditions of low-wage workers,” said Ken Jacobs, chair of UC Berkeley’s Center for Labor Research and Education. “We are seeing an upsurge of worker actions. Unions are playing a leadership role. Their members’ lives are at stake.”

A hotel housekeeper, victim of a coronavirus layoff, struggles to support her three kids. ‘I just want to keep my little family together,’ she says.

Organized labor is assisting not just its own members but also protesters at nonunion companies. The International Brotherhood of Teamsters is backing Amazon warehouse workers. The United Food and Commercial Workers International Union is helping organize Instacart shoppers. The Service Employees International Union is funding fast-food activists and Uber drivers.

“Even before the pandemic, workers were living on the edge financially,” said Ron Herrera, president of the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor, which represents 800,000 union members. “This crisis has been the glue for workers to come together, blue-collar and white-collar, not just union members. It sounds corny, but we’re moving towards a worker rebellion.”

Others are less sanguine about the prospects for a worker uprising when more than 30 million people in the U.S. have filed for jobless benefits.

“During the last recession, it was very hard to organize,” said Assemblyman Ash Kalra (D-San Jose), chair of the Assembly Committee on Labor and Employment. “When unemployment is high, people just want to get back to work.”

Nonetheless, he said: “These direct actions are inspiring workers to believe they have power. McDonald’s workers in San Jose got plexiglass separators and protective gear after a four-day strike. And they weren’t terminated — which never would have happened before.”

Still, if the pandemic’s economic fallout is crippling businesses, it is also slamming the finances of unions in hard-hit occupations such as hospitality and entertainment. At Unite Here, which represents 307,000 workers at hotels, casinos, airports and stadiums nationwide, 98% of members have been laid off.

“This is a cataclysm,” said Kurt Petersen, co-president of Unite Here Local 11 in Los Angeles, which furloughed nearly half its staff of 110 as dues from 32,000 members dried up. “It’s hard to comprehend just how far we have fallen, and when we can ever expect to come out of this.”

Nurses know how unprepared we were for COVID-19. They’re getting punished for speaking out.

Local 11 has organized mass food distributions with other unions and rallied volunteers to help more than 1,000 members apply for unemployment benefits. “People text me asking, ‘When’s the next food bank?’” Petersen said. “It breaks my heart.”

He doesn’t see labor’s political clout diminishing. In recent weeks, Local 11 volunteers have telephoned 25,000 members, spurring a mass lobbying push for local job security and safety measures.

“We’re on the offense, not the defense,” Petersen said.

Businesses, many of them crippled by stay-at-home orders and a collapse in consumer spending, are watching the activism in dismay.

“The unions have fully gone for it,” said Stuart Waldman, president of the Valley Industry and Commerce Assn. in Van Nuys. “They’re pushing the envelope.”

Waldman and leaders of other business groups fought Los Angeles unions over the city’s new ordinance requiring large companies to offer workers affected by COVID-19 an additional 10 days of paid sick leave beyond the current six-day requirement.

And they unsuccessfully battled new laws, backed by Unite Here and SEIU, that will force L.A. hotels and janitorial companies to offer jobs to laid-off workers based on seniority after they reopen. Even businesses that change ownership must grant former employees the right to return to their old jobs.

Waldman describes the measures, signed by Mayor Eric Garcetti on Wednesday, as “anti-millennial. Your most senior people may not be your best people.” Unions say they protect employee activists and prevent age discrimination — and hope to extend them statewide.

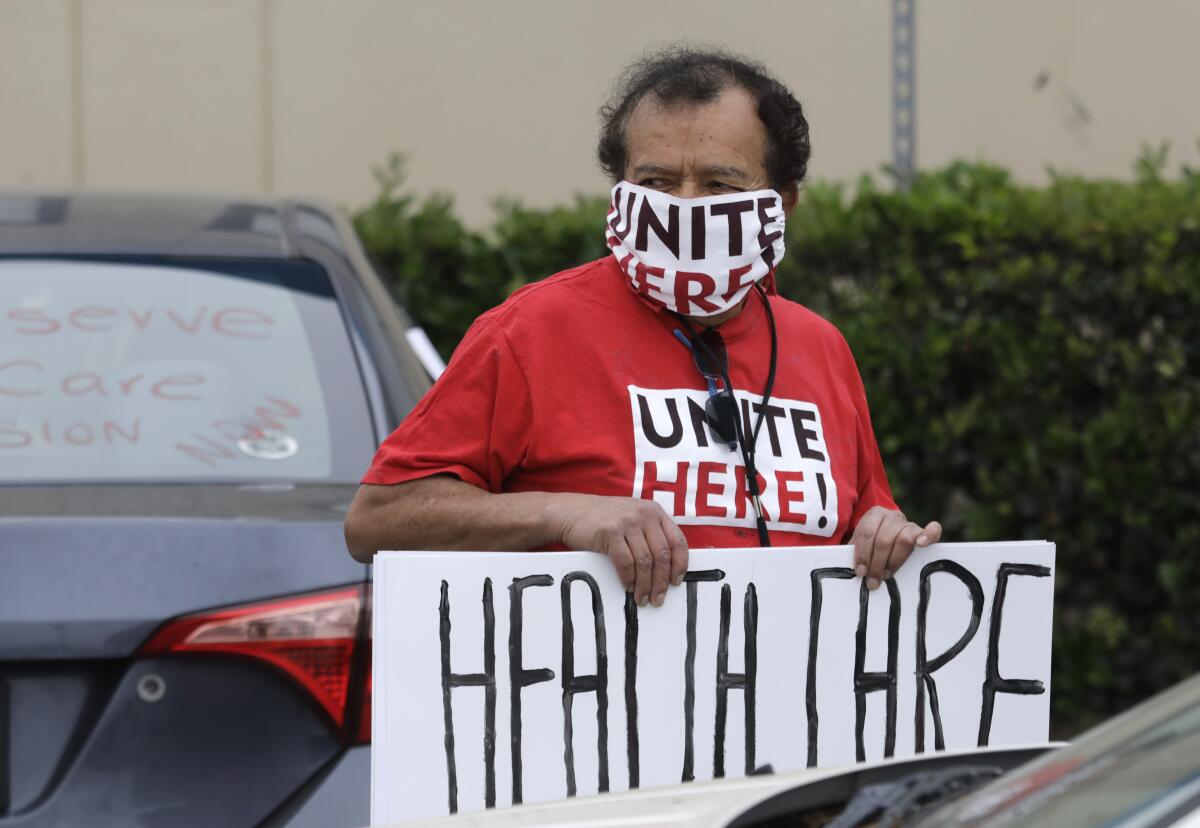

Health insurance is another battleground. With Los Angeles International Airport all but shut down, Unite Here activists last week persuaded the City Council to condition rent relief for airport concessions on continuing to pay medical benefits for 4,000 laid-off food service and retail workers.

For Karla Cortez, a single mother who earned $18.90 an hour as a saleswoman at an LAX skincare boutique, that was “a big blessing.” Cortez, who was laid off April 2, had a bout with thyroid cancer five years ago and knew cancer survivors could be vulnerable to COVID-19.

When the pandemic hit, “I wondered how I’d survive,” she said. Her thyroid medication costs $50 a month under her healthcare plan. If benefits disappear, it would cost $1,000 a month.

Along with other Unite Here members, Cortez, 46, circulated petitions and sent video testimony to airport officials and City Council members. “Without the union, we’d be in big trouble,” she said.

On Thursday, a caravan of 80 cars snaked along Century Boulevard as hotel workers hoisted signs reading “Healthcare for All,” part of a Unite Here campaign to pressure LAX-area hotels to extend medical benefits for laid-off employees.

“Hotels are getting money in the federal bailout,” Petersen said. “They should use some of that to pay workers’ healthcare.”

Organized labor has also sought new gains in Sacramento.

On April 16, after fierce lobbying by the UFCW, Newsom signed an executive order requiring food sector companies that employ 500 or more workers to give two weeks of supplemental paid sick leave to any who contract COVID-19 or are exposed to the virus.

Before the order, just 14% of California workers were entitled to as much as two weeks of paid sick leave for any illness. (State law mandates just three days.) As COVID-19 spread, some companies expanded leave, but Newsom’s order applies to all major groceries, restaurants, fast-food chains, food processing and packaging plants, farms and delivery services.

UFCW Local 770, which represents 20,000 grocery workers, had already spurred new safety ordinances in the city and county of Los Angeles after some stores had warned workers not to scare customers by wearing masks. Now stores must provide masks and sanitizer to workers, and customers must wear face coverings too.

Still, the union is clamoring for stricter enforcement. On Tuesday, it mounted a Koreatown caravan protest demanding that Kroger step up protections in its Food 4 Less stores. Signs scrawled on the car windows read, “No more new infections.”

Ralphs’ May Day protest was scheduled after 16 workers at the Sunset Boulevard store tested positive.

One statewide initiative is the focus of an intense struggle. The California Labor Federation is pushing to expand workers’ compensation insurance to automatically cover COVID-19 infections or doctors’ quarantine recommendations for healthcare, law enforcement, grocery, warehouse, transportation and other front-line employees.

“Workers should not have to fight denials and delays while fighting for their lives,” federation chief Art Pulaski wrote Newsom and legislative leaders March 27.

Employers contend that would cost them billions of dollars when it is often unclear if infections originate in the workplace.

“Many businesses and their owners are casualties of the necessary economic shutdown,” Allan Zaremberg, president and chief executive of the California Chamber of Commerce, wrote in an April 7 response signed by more than 70 business groups. “They cannot be expected to shoulder a new employer-financed social safety net.”

Labor groups have organized mask donations for their members, some emblazoned with union logos.

One union was perhaps too eager to intervene: In March, the SEIU’s United Healthcare Workers West branch announced it had arranged to buy 39 million highly protective N95 masks for California hospitals and government agencies. By early April, federal authorities determined the union had been duped by shady middlemen.

At a CVS warehouse in La Habra last week, Teamsters Local 952 distributed masks to truckers and warehouse workers inscribed “952 HERO.” Two workers had tested positive for COVID-19 after the union complained to CVS for weeks about a lack of masks and hand sanitizer, as well as a failure to enforce social distancing.

Anger escalated after a CVS memo circulated telling employees how to mix their own bleach solution at home. And workers are upset CVS has declined to offer $2-an-hour hazard pay boost, which employees at a nearby Albertsons warehouse receive. Last week, fliers appeared on parking lot windshields threatening a wildcat strike.

“CVS has insulted our members,” said Eric Jimenez, Local 952’s principal officer. “They offered us a one-time bonus of $300, but if you called in sick you couldn’t get the bonus.”

CVS spokesman Michael DeAngelis said in an email that the bonus is available to any worker who falls ill. “We are constantly working to increase the availability of supplies and update protocols to help ensure the safety of our employees,” he wrote. “Refreshed mask supplies are available weekly and we have put in place social distancing guidelines.”

Whether it is slog-it-out bargaining over safety measures or bold legislative moves, unions see their coronavirus activism as the beginning of a new era for the labor movement.

“It takes a pandemic to wake workers up,” Jimenez said. “Without a union, how many people can walk in to complain about safety without the fear of retaliation? Unions can hire lawyers and call politicians. We’ve shown our members somebody cares.”

Herrera, the county labor federation chief, predicts unions will ramp up organizing after the pandemic.

“Workers are clearly seeing the inequities and the lack of protections,” he said. “They’re seeing the advantages of being a unionized worker. There’s a resentment in the workplace that we have to take advantage of.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.