Retail thought it was facing the apocalypse. Then came the coronavirus

As operator of one of the country’s biggest liquidators, Bryant Riley has profited from what’s been called the retail apocalypse — the destruction of shops and big chains largely because of competition from online upstarts.

In retrospect, the term might have been thrown about a bit loosely over the last decade considering what’s happening today: the sudden and indefinite closure of countless stores across the nation and the likelihood that many will not reopen.

“Nobody planned for a zero-revenue scenario,” said Riley, chairman and co-chief executive of B. Riley Financial, an L.A. company that owns Great American, which liquidated Payless, Toys R Us and other big chains either solely or with partners. “I think you are going to see a lot of liquidations, toward the end of the year most likely.”

More than 15,000 stores could permanently close this year, according to Coresight Research. That’s approaching double the 9,548 stores that big chains announced they would shutter in 2019, a particularly brutal year for retail with the bankruptcies of Payless, Gymboree, Charlotte Russe and others.

The year had started out well with 2,910 openings and 1,883 planned closures through March 22 — far under the 5,399 closures that were announced for the same period last year. Coresight had predicted closures to pick up by the end of the year to roughly 8,000, but that’s barely more than half the number expected now.

The toll of virus-related closures, which for now are temporary, is immense, with at least 600,000 mostly low-wage workers furloughed last week despite President Trump signing a $2-trillion stimulus package that includes billions in loans to damaged industries.

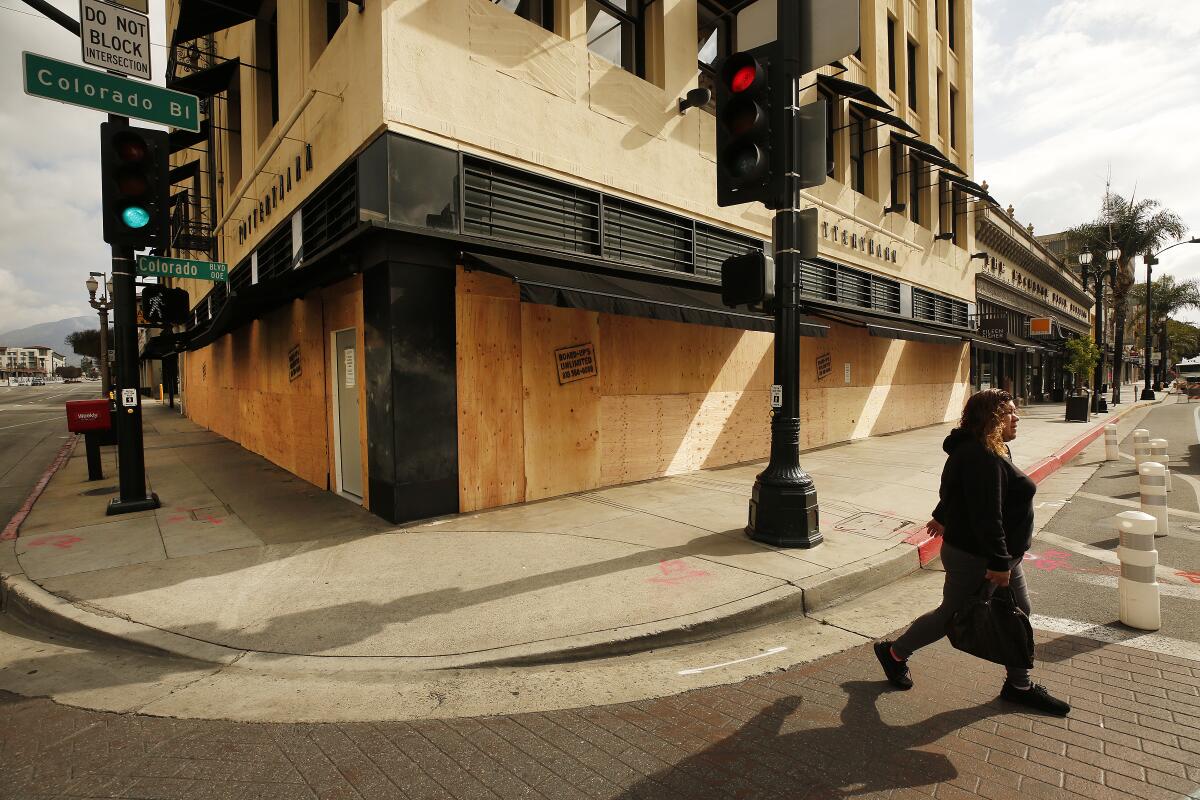

Among the chains that announced furloughs were Macy’s, Gap and Kohl’s. The collateral damage extends to commercial landlords. Taubman Centers, the owner of the Beverly Center and other upscale malls, warned tenants that they still needed to pay rent because of its own obligations to lenders and service providers, while New York City has reported a sharp rise in burglaries of closed stores, prompting owners to board up there and elsewhere.

Liquidations have been big business since last decade’s financial crisis, which saw Circuit City, department store chain Gottschalks and other stores close. More recently, amid the continuing shift to online sales, there have been a host of shutdowns by chains such as Toys R Us. Critics blame some of the failures, including Payless, on leveraged buyouts by private equity owners who loaded firms up with cheap debt to pay themselves dividends.

Riley said the current crisis hit as many oversized retailers were still trying to figure out how to best reconfigure themselves in the new retail environment. “There are a lot of companies out there that still have too much debt. If you look at any big box or small box, it’s not been thriving and they’ve been trying to get their footprint down to a place that made sense for them,” he said.

Retail’s ongoing struggles have been good business for anyone who makes money dealing with distressed companies. That includes Great American, a Woodland Hills company that prior to its 2014 merger with B. Riley had a long track record of liquidating marquee brands such as Borders and Tower Records.

Liquidators typically make money by bidding for the assets of bankrupt companies they believe are valuable and then holding closeout sales. They also work with companies that are seeking to downsize by shuttering outlets. Great American has another business conducting collateral appraisals for lenders. “We understand assets,” Riley said.

B. Riley, a diversified publicly traded company, provides other services to distressed retailers so liquidation isn’t the only way out of a financial jam. The company provides loans, forensic accounting and restructuring advice — and has used such wherewithal to get a piece of distressed businesses.

Bebe, the women’s apparel retailer, closed all of its stores a few years ago and became a brand business with help from a $32-million loan issued by B. Riley that was converted into a minority equity stake. “We looked at taking this liquidation business and trying to create some different results,” he said.

B. Riley’s stock has benefited from the booming business of its Great American unit, with shares climbing from under $9 in 2016 to a high topping $30 in November, before being battered in the recent market sell-off.

Gary Wright, founder of G.A. Wright Sales, a Denver-based marketing company that does sales promotions and liquidations, said he’s gotten “frantic” calls from some retailers about how to handle reopenings given that the shutdown is a “blow to retailers that they’ve never seen before.”

“I don’t believe that brick-and-mortar retailing is ever going to go away, but certainly it will contract considerably and it already has,” said Wright, whose diverse client list has included Louis Vuitton, Ace Hardware and now-defunct retailer Casual Corner.

A playbook for surviving the crisis, he said, would involve cutting expenses to the “bare bones” and getting a rent abatement from the landlord, a break on debt payments from lenders and a government loan. Then, once mandatory closures lift, he expects there will be pent-up demand.

“They have spent two or three months not being able to sell inventory on the floor. Manufacturers may have continued to ship to them. They are not going to have enough cash and they are going to be overstocked — that’s a problem we are really good at solving,” said Wright, who expects to handle more promotions than liquidations once the coronavirus outbreak is over.

“The question is of course did they dig a hole while they were closed that was so deep that they are not able to find their way out of it?” he said.

One of the few hopes that retailers have to dig themselves out of “the greatest crisis we will hopefully see in our lifetime” is to start planning the all-important Christmas season, said Deborah Weinswig, chief executive and founder of Coresight, a global retail and technology advisory firm.

“If retailers are focused on that, I think we do see less bankruptcies and less permanent store closures. If they are just focusing on the immediate, we are in hell, which is what this is,” she said.

Erika Morabito, a partner at Foley & Lardner in Washington, D.C., who handles bankruptcy and restructurings, expects a wave of bankruptcies across multiple industries. “COVID-19 is going to change the world and many different companies and industries in terms of how they do business. It’s just inevitable,” she said.

Even before the outbreak, her firm had a lengthy “watch list” of troubled retailers that included J.C. Penney, Macy’s, Rite Aid, Neiman Marcus and Bed Bath & Beyond. She said that everyone is in the “triage stage right now, which is ‘How does this impact my business and what relief can I get from the government?’”

The crisis is so unprecedented that it has upended bankruptcy proceedings already underway. Restaurant owner CraftWorks Holding and home furnishing retailer Pier 1 have sought to mothball their operations in their current Chapter 11 bankruptcies as the outbreak has either completely dried up, or significantly reduced, revenues anticipated by earlier court-approved proposed operating budgets.

“Who knows how long this will last, so I think companies are sitting back waiting to see what judges are going to do,” Morabito said.

CraftWorks, the Nashville-based owner of several eateries, including Gordon Biersch Brewery Restaurants, filed for bankruptcy protection March 3 with plans to sell itself, but then fired most of its 18,000 workers last week after having to shut restaurant doors.

Morabito added that a disturbing trend she is witnessing with clients is lenders playing hardball if borrowers don’t meet all loan covenants, which typically might require adherence to a certain cash flow figure or other financial metric. Prior to the outbreak, covenant violations might prompt a bank to seek new financial projections, but suddenly banks are requiring onerous terms more consistent with a payment default, such as additional collateral. “Everybody is worried,” she said.

Weinswig at Coresight said it appears the retail sector was not overly impressed with the $2-trillion stimulus package, which is why chains announced furlough after furlough last week. Clothing retailers face particular challenges because the industry is losing its spring season, leaving it with huge inventories of dated clothes. Weinswig said she spoke to a fast-fashion chain that was considering holding on to its inventory for next spring.

“Normally we would see them flood T.J. Maxx or Ross or have this product end up in a landfill or barter it for advertising,” she said. “There are all kinds of things that happen to old inventory.”

Retailers also are interested in getting their fresh inventory to China where sales can be robust on the Alibaba e-commerce platform, Weinswig said. Well-positioned companies include Lululemon Athletica, Estée Lauder and L’Oréal, which did big business on International Women’s Day on March 8 with livestreaming and other special marketing. But doing so, she said, takes three to four months and involves setting up an online store and payment processing, as well as shipping inventory to the platform’s warehouses.

“I am looking for every silver lining that I can get, because there are so few,” said Weinswig, whose consultancy helps American firms enter the Chinese market.

Hain Capital Group is another company well positioned to do big business given the expected surge of bankruptcies. The company buys up receivables — money due for goods or services provided — and other claims that creditors have against bankrupt companies. That provides money to creditors who need it fast, while allowing the firm to profit from later payouts it expects from the court.

The New Jersey firm bought claims from suppliers to Toys R Us, contractors who serviced PG&E and creditors in many other cases, including the bankruptcies of Lehman Bros. and General Motors during the financial crisis. Over the last 10 years, investors in Hain’s fund have enjoyed 15% annual returns, said founder Robert Koltai, who expects the outbreak will “disenfranchise” most traditional retailers while “turbocharging” online sellers.

“This is an act of God. It’s beyond our contemplation. The economy across every single platform has stopped but for a couple of insular industries like medical products,” he said. “The question I’ve been posing to everyone is: ‘You tell me the next time you want to go out for a dinner or a concert, and that’s when this will be over.’”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.