Column: The coronavirus bill is a big step toward stimulus that helps you, not corporate bigwigs

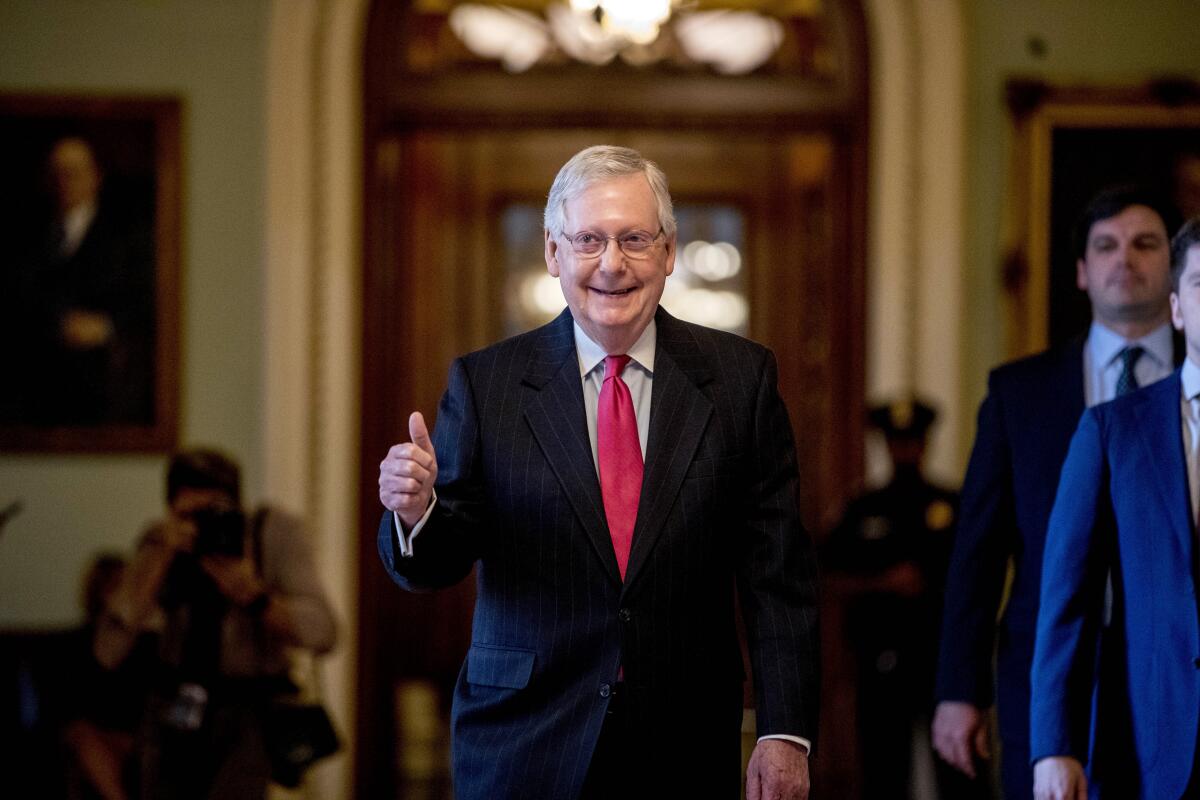

Someone was paying attention to the lessons of the last bailout.

The $2-trillion stimulus bill on which Congress will start voting Wednesday includes several provisions aimed at making sure that the government’s massive bailout of big business comes with at least some strings attached and that ordinary households get help.

As we write, much of the measure is still under wraps, though portions have been making their way into the public sphere droplet by droplet. A draft described as “near final” has also been released by the Senate. We’ll outline what we’ve seen, and update as more details emerge.

There’s not much that a small thousand dollars can do for a family if they are out of work and still need to pay rent, student loans, major consumer loans, a mortgage, etc.

— Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.)

— The good: The measure includes a one-time stimulus payment to families of up to $1,200 per adult and $500 per child, phasing out for households with earnings of $75,000 for singles and $150,000 for couples. Singles earning $99,000 and couples earning $198,000 won’t get the checks.

Democratic negotiators managed to eliminate a Republican provision that would have reduced payments to low-income households. Now everyone up to the phase-out threshhold will be eligible for the full amount.

Unemployment insurance payments are massively pumped up. The bill provides for payments of $600 per week to all unemployment claimants for four months (raised from the three originally proposed by the Senate GOP) on top of every state’s standard unemployment payments.

Congress is about to make huge mistakes with the next bailout, says a veteran of the last bailout

On average, says economist Arindrajit Dube of the University of Massachusetts, this will bring the unemployment compensation rate to close to 100% of pre-crisis pay for laid-off workers.

“Feds pay for it all,” Dube tweeted. “This is a big deal.” The federal payment will overcome the cheeseparing benefits of many states, which range from a high of $795 per week in Massachusetts to only $235 in Mississippi.

For those who don’t qualify for conventional unemployment benefits, such as the self-employed, gig workers or people forced to leave their jobs to care for children or others in the household, the bill provides a special pandemic benefit amounting to half the state average benefit plus $600 a week.

The bill also provides a foreclosure moratorium of at least 60 days, starting March 18, on homes with mortgages backed by the federal government, including mortgages held by the government sponsored agencies Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac or insured by the Dept. of Veterans Affairs or the Dept. of Agriculture. Owners of those homes can also apply for payment forbearance by showing they face financial hardship in the crisis.

The measure provides for some oversight of $500 billion in bailout funding for large corporations, though the powers of the oversight bodies aren’t clear. One provision that seems to be ironclad (on the surface) is a ban on any bailout funds going to businesses owned by President Trump or his offspring, Vice President Pence, members of Congress or heads of executive departments.

This could be a major safeguard to keep taxpayer funds from being diverted into the pockets of an administration that has set new standards for official turpitude.

Big businesses that accept bailouts from the $500-billion bailout fund will have to accept mandates on how they spend the money. They’ll be barred from staging share buybacks or paying dividends until one year after the bailout funds are paid back.

President Trump, Elon Musk and other are spreading dangerous myths about coronavirus.

They’ll also have to commit to maintaining until Sept. 30 the same employment levels in place Tuesday “to the extent practicable,” but in any event barred from cutting employment by more than 10%.

The measure includes other provisions aimed at encouraging businesses to avoid layoffs. These include a credit against payroll taxes (that is, Social Security and Medicare taxes) based on an employer’s continuing payroll, and a program of loan forgiveness for small-business loans, chiefly through the Small Business Administration, taken out by employers who keep their workforces in place.

— The bad: The bill incorporates limits on executive compensation at companies accepting bailout funds, but they arguably don’t do much to rein in excessive pay. That’s an issue, because previous bailouts have been used not to retain rank-and-file workers or make productive investments in business, but to fatten the paychecks of top executives.

No employee of a bailed-out company earning more than $425,000 in 2019 (except those who receive the pay through a union contract) would be eligible for a raise or a golden parachute — that is, severance — worth more than twice their 2019 compensation.

Those earning more than $3 million, however, would be eligible for raises worth half of their 2019 compensation in excess of $3 million.

“The failure of Senate leaders to secure meaningful CEO pay limits helps nobody except top executives,” said Sarah Anderson, executive compensation analyst at the Institute for Policy Studies.

As Anderson calculated, the rules might force businesses to pare their CEOs’ compensation, but only from elevated levels. If American Airlines CEO Doug Parker, who earned $12 million in total compensation in 2018, got the same last year, he’d be eligible for $7.5 million this year, Anderson calculated. If Delta CEO Edward Bastian got the same $15 million last year that he received in 2018, he’d still be in line for $9 million this year.

In recent days, alarm about the economic impact of the novel coronavirus have turned conservatives who weeks ago were boasting about the shrinking of the U.S. government into raving Keynesians, proclaiming the virtues of deficit-financed economic stimulus.

The limits on compensation would apply to most companies until one year after the bailout is repaid. For airlines, which will be in line for a special $50-billion loan program, the ban would last for two years, or until March 24, 2022.

Eagle-eyed analysts are still poring over the language of the bill, but one provision sheltering in place and unearthed by the Washington Post is a special $17-billion bailout for Boeing. The bailout, which takes the form of loans and loan guarantees, doesn’t mention the company by name and is concealed behind innocent-sounding language referring to “businesses critical to maintaining national security.”

Boeing would get this benefit even though it’s one of the least deserving bailout candidates. The company has squandered its cash resources for years in stock buybacks — $43 billion from 2013 until two fatal crashes of its 737 MAX aircraft in 2018 and 2019 awoke it to the idea that maybe it should conserve cash.

As recently as Tuesday, Boeing CEO David Calhoun was taking a truculent approach to the prospects of a bailout, telling Fox Business Network that he would refuse government money if it required turning over an equity stake to the government, an idea that had been floating around in Washington.

“I don’t have a need for an equity stake,” Calhoun said. “If they forced it, we’d just look at all the other options, and we have got plenty.”

Fine. Let Boeing choose among its “plenty” of other options.

— The uncertain: At the insistence of Democrats, the Senate Republicans abandoned their plan to grant Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin extraordinary discretion over the $500-billion corporate bailout. The proposal would have allowed the Treasury to keep secret for six months the identities of the recipients or their terms, and failed to provide for any public oversight.

FDR’s New Deal aimed not to stimulate the economy, but protect families from hardship.

The final bill eliminates the secrecy and creates an oversight process comprising a special inspector general empowered to audit the disbursement of pandemic bailout funds and charged with reporting quarterly, as well as a five-member congressional oversight board.

These provisions conform, superficially, to the process established in 2008 to oversee the financial industry bailout of that era. As that program’s former inspector general, Neil Borofsky, told me this week, oversight and transparency is indispensable for ensuring that taxpayer funds aren’t misused.

Borofsky also warned that the overseers should expect considerable pushback from the government officials, who won’t appreciate being second-guessed. A lot will depend on the character of the special inspector general, who will be appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. If he or she is just a front for the Treasury, the public interest will be left in the gutter.

That’s especially so since there don’t seem to be provisions granting the overseer subpoena power or any method of enforcing a request for documents other than filing a complaint with Congress. That’s not enough.

Damon Silvers, an AFL-CIO counsel who was deputy chair of the Congressional Oversight Panel for the 2008 bailout, underscores the risks of having oversight without authority. The bailout inspector general could examine deals after the fact, but couldn’t stop them from happening in the first place, he observes.

The oversight panel “had no power at all,” Silvers says. “It was purely advisory. It had no subpoena power, and it could not swear in witnesses. Officials came in front of us and lied with impunity.” Will the experience of the new overseers be any different? Perhaps, but since they won’t have powers that the last group had, don’t bet on it.

— Still missing: There’s reason for concern that the provisions for household assistance — that is, the bailout of ordinary Americans — won’t be enough to get millions of people through the ongoing crisis.

The stimulus deal provides for loan forgiveness for businesses, but none for households facing unrelenting pressure to pay their mortgages, rent, and other bills while their income is slashed or cut off completely.

As Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-New York) put it, what’s needed by many families is a mortgage and rent moratorium, at least for the duration.

“There’s not much that a small thousand dollars can do for a family,” she said, “if they are out of work and still need to pay rent, student loans, major consumer loans, a mortgage, etc.”

Also missing is a federally mandated enhancement of paid sick leave for American families. The first coronavirus bill, signed by President Trump on March 18, included sick leave benefits for employees at small to medium-sized firms forced to leave work because of the coronavirus.

But as my colleague Jim Peltz reports, it left uncovered as many as 20 million workers by exempting employers of 500 workers or more and allowing small businesses to seek hardship exemptions. Covered full-time workers would get up to two weeks of paid leave, and part-time workers would get a period of leave equal to the number of hours they work on average over a two-week period.

The payments would be capped at $511 a day for those who are sick with the virus or seeking care, and $200 a day for those caring for a sick family member or children.

That may not be enough to cover the period of the emergency, and certainly not enough to meet standards set by other developed countries, many of which provide for higher compensation over longer periods.

In other words, the battle to ensure that American workers can get through the pandemic is not over yet.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.