Column: You paid off your student loans. You should still support canceling them for others

A major consequence of the ending of Elizabeth Warren’s presidential campaign is the loss — at least for now — of a voice so adept at explaining how progressive policies work to the benefit of all Americans, regardless of their station in life.

The best example of this may have come in January, when Warren responded to a voter outraged that, after he had paid student loans, she was proposing that those in the same situation get relief.

Warren’s questioner stalked away before she could fully answer his complaint, but she finished her explanation a few days later on CBS (though she had to talk over a preening anchorman’s interruption to do so).

America has made progress mostly when living standards for the majority of the nation’s citizens are advancing. Leaving aside the depression of the 1930s, the opposite has been true when incomes have stagnated or fallen.

— Economist Benjamin M. Friedman

“Look, we build a future going forward by making it better,” she said. “By that same logic, what would we have done, not started Social Security because we didn’t start it last week for you or last month for you?”

Warren was confronting, with typical clarity, one of the most common objections to policies that fix manifest injustices: “I suffered, so why shouldn’t everyone else?” Sometimes the point is articulated through its converse: “I got mine, too bad about you.”

The same question was raised Wednesday by Republican political operative Matthew J. Dowd, who tweeted, “I paid for my college by working and i took out student loans which I paid back in less than ten years by scrimping on other things. Why is it fair that we just cancel all student loan debt?”

This is perhaps the most narrow-minded and shortsighted argument on public policy one can imagine. Applied more broadly, it’s a vote for total political stasis.

Seema Verma, an Indiana health consultant and bureaucrat nominated by President Trump to run Medicare, Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act, put in a word for individual choice on health insurance benefits during her confirmation hearing last week.

That’s because every social problem addressed by political leaders comes to their attention because it has afflicted some portion of the population. Refusing to correct a manifest injustice out of solicitude for the suffering of previous victims is asinine.

Taking a line from Warren’s point, we got child labor laws because generations had their whole lives stunted by the loss of their childhood. Social Security because of the spectacle of America’s seniors homeless and starving in the wake of the Great Depression. We got Medicare and Medicaid because the project to bring healthcare to elderly and low-income Americans was still unfinished after the 1940s.

We’re talking about canceling student debt because we recognize as a society that those who had to scrimp and save to get themselves or their offspring through university should not have needed to do so.

We understand — or should, at any rate — that all these needs are properly the concern of the entire community, not merely those immediately affected.

America used to be much more tolerant of programs that aimed to improve social justice. What changed? Benjamin M. Friedman, who has made studying the moral consequences of economic changes his life’s work, has posited that economic inequality has sapped American society of its tendency toward fellow feeling.

“America has made progress mostly when living standards for the majority of the nation’s citizens are advancing,” Friedman wrote in 2009. “Leaving aside the depression of the 1930s, the opposite has been true when incomes have stagnated or fallen.”

The student debt crisis reentered the news cycle Monday (has it ever really gone away?) when Sen.

The effect of shrinking economic prospects is corrosive on society, he observed. “The economically self-protective instinct ... underlies so much of what emerges as intolerant, anti-democratic and ungenerous behavior — racial and religious discrimination, antipathy toward immigrants, lack of generosity toward the poor.”

Unscrupulous politicians know how to exploit this phenomenon. Today, in a period of unexampled economic inequality, it’s common to hear progressive policies demogogued as giving someone something for nothing.

Consider the claim that the Affordable Care Act is flawed because it mandates that maternity coverage be part of every health insurance policy. President Trump’s Medicare and Medicaid chief, Seema Verma (now part of his coronavirus task force), aired that one out during her confirmation hearing in 2017.

“Some women might want maternity coverage, and some women might not want it or feel that they need it,” Verma said then. “I think it’s up to women to make the decision that works best for them.” The line had been pioneered by the anti-Obamacare conservative Rep. Renee Ellmers (R-N.C.), who challenged then-Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleein Sebelius to explain why men should have to pay for maternity coverage in their health insurance plans.

“To the best of your knowledge, has a man ever delivered a baby?” Ellmers asked, thinking she had found the ultimate “gotcha.”

As we explained for Ellmers’ and Verma’s benefit, while no man has ever delivered a baby, no baby ever has been born without a man being involved somehow. If you limit maternity coverage to only women of childbearing age, you’re placing the entire financial burden of propagating the species on the shoulders of women aged roughly 18 to 38.

Society, moreover, has a vested interest in healthy mothers and newborns. Unhealthy babies and mothers impose a cost on the entire community, as a squandering of human capital and a generator of costs for treatments that often would have been unnecessary if mothers got the care they needed during pregnancy.

Yet, prior to the ACA, when insurers could exclude medical conditions from coverage at will, only 12% of policies in the individual insurance market offered maternity coverage.

That’s the underlying rationale for creating consumer protections for medical patients seeking insurance, or seniors needing retirement security, or students burdened by outrageous levels of debt.

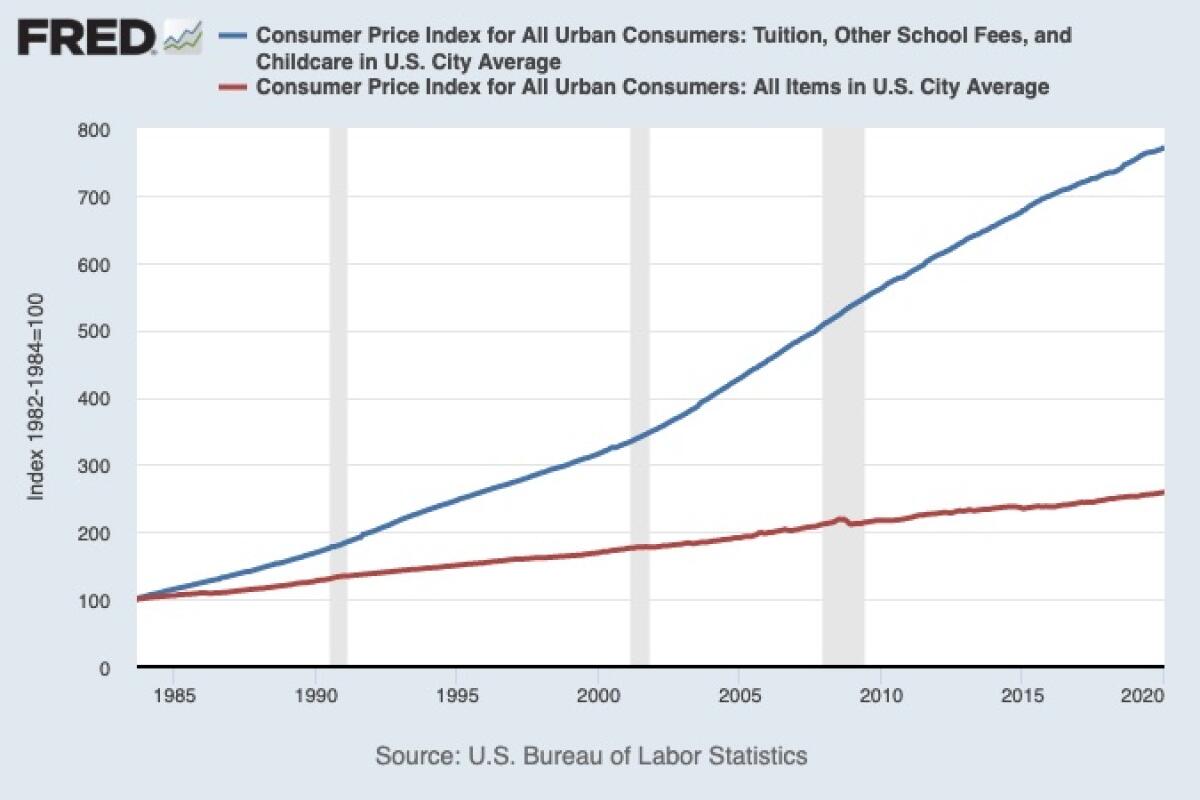

But there’s more. Some of these social problems have grown much worse as they’ve been passed down from generation to generation without being fixed. The cost of higher education has soared as a proportion of median household income. Matthew Dowd is now in his late 50s, so he presumbly attended college in the late 1970s or early ’80s.

In those times gone by, the average cost of attending university came to $4,885, or about 20% of the median household income, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Today it’s $23,872, or 36.6% of the median income. For private institutions the growth has been even greater: Private tuition came to about 40% of the median income in the mid-1980s, and 64% today.

The financial burden is therefore commensurately worse for today’s families, and the opportunities for economic mobility through education slimmer. To quote Warren, “We don’t build an America by saddling our kids with debt. We build an America by saying we’re going to open up those opportunities for kids to be able to get an education without getting crushed by student loan debt.”

Warren says she will continue to speak out on these and other issues. That’s fortunate. We need someone who can explain so clearly why we need each other.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.