Column: COVID-19 could kill the for-profit science publishing model. That would be a good thing

Of all the ways the current coronavirus crisis has upended commonplace routines — such as disrupting global supply chains and forcing workers to stay at home — one of the most positive is how it demonstrates the value of open access to scientific research.

Ferreting out a silver lining in an event that has produced the infection of more than 90,000 individuals and taken the lives of more than 3,000 — and is certain to wreak further destruction before it is quelled — is a delicate matter.

But the emergence of the virus causing the condition known as COVID-19, first reported by Chinese authorities in late December, has resulted in an unprecedented level of collaboration among researchers worldwide.

The data surrounding the biology, epidemiology, and clinical characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 virus have been growing daily.

— Journal of the American Medical Association

That underscores that this virtually real-time sharing is the exception in scientific research, not the rule. Nor is it universally observed.

According to the Journal of the American Medical Assn., “The data surrounding the biology, epidemiology and clinical characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 virus [the virus causing the current outbreak] have been growing daily, with more than 400 articles listed in PubMed.” That’s a free database of research papers maintained by the National Institutes of Health.

Among the major violators of the principle that a crisis demands more information, not less, is the U.S. government.

On Monday, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which should be the clearinghouse for timely information about the outbreak, abruptly canceled a briefing by infectious disease expert Nancy Messonnier, without explanation.

By limiting sick leave and free healthcare, the U.S. system will promote the spread of coronavirus.

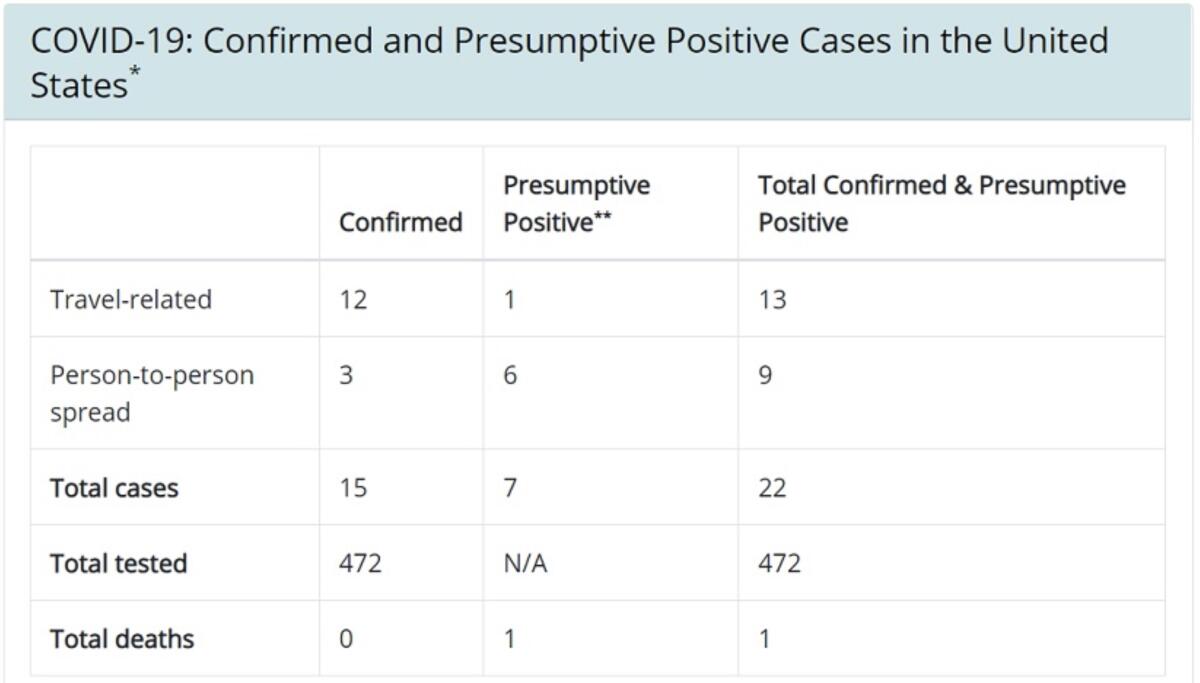

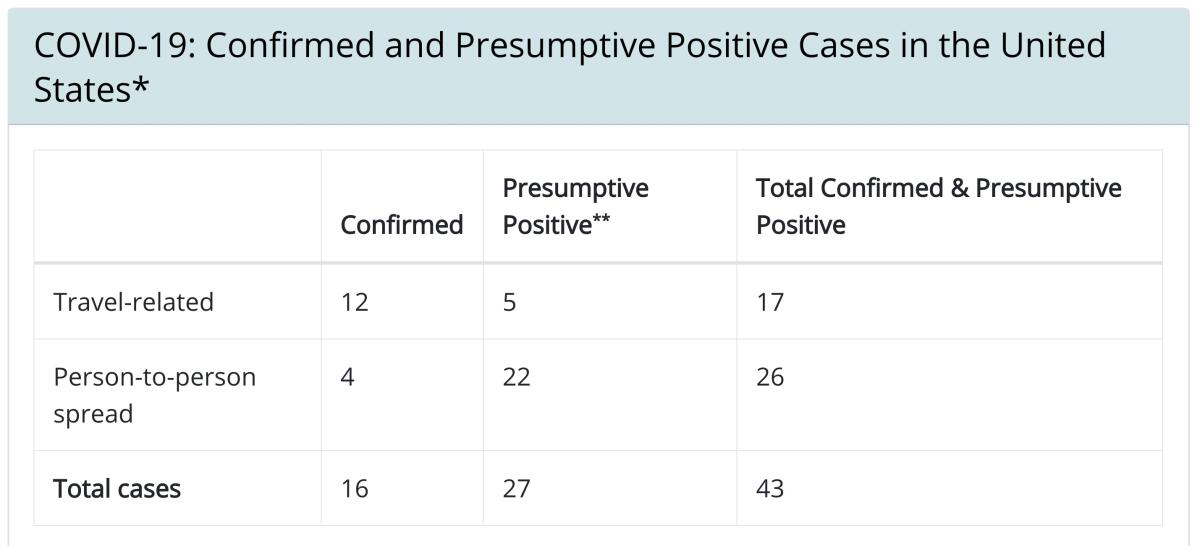

As Politico first reported, the agency also quietly removed data on its website about the number of people tested for the virus in the United States, possibly out of embarrassment about technical glitches that prevented thousands more tests to be administered.

That’s a crucial information gap, because knowing how many people have been tested would help determine how far and how quickly the virus has been spreading in the U.S., as well as the effectiveness of the government’s management of the crisis.

What’s most intriguing about the effect of the COVID-19 crisis on the distribution of scientific research is what it says about the longstanding research publication model: It doesn’t work when a critical need arises for rapid dissemination of data — like now.

The prevailing model today is dominated by for-profit academic publishing houses such as Elsevier, the publisher of such high-impact journals as Cell and the Lancet, and Springer, the publisher of Nature. But it’s under assault by universities and government agencies frustrated at being forced to pay for access to research they’ve funded in the first place.

The critics support an “open access” model, through which research grant institutions pay fees for publication but require that their funded research be made accessible without charge.

Elsevier, Springer and other commercial publishers have temporarily dropped their paywalls on coronavirus-related research, but they say the action is limited to the duration of the crisis and doesn’t apply to other published research.

“The responsible thing to do is to make all research freely available during epidemics or possibly pandemics where there are people at risk,” Edward Campion, executive editor of the New England Journal of Medicine, told the Canadian journal the Scientist.

Among the leaders in the open-access movement is the University of California, which ended its subscriptions to about 2,500 Elsevier journals after it failed to come to terms with the publisher on liberating access to UC research.

Businesses and governments haven’t been prepared for the coronavirus, so neither are we.

The university proposed that its annual subscription bill of about $11 million cover not only access to the Elsevier journals but publication fees for articles that would be made freely available. Elsevier balked, and shut off UC’s access to the journals in July. The university has assured faculty and students that they can gain access to needed research through other legal means.

“The [scientific] literature is controlled by largely commercial journals,” says Randy Schekman, a Nobel laureate biologist at UC Berkeley who founded ELife, a nonprofit open-access publisher, in 2011 with support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and other backers. “Decisions are made by professional editors who are in the business of selling magazines, which make a huge profit by virtue of controlling copyright on the literature and by controlling access to the literature.”

Research consortiums in Germany and Sweden have dropped their subscriptions to Elsevier, though the publisher has been able to work out compromises in other countries, including Italy and the Netherlands.

The commercial publishers, aided by professional organizations that publish revenue-producing journals, still have the clout to lobby effectively on their own behalf.

“These forces continue to exert undue influence on decisions made by the government,” Schekman told me. He pointed to the derailing of an expected initiative from the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy to make federally funded research immediately free to the public. The plan would resemble the so-called Plan S proposed by a coalition of 19 public and private research-funding organizations in Europe.

The coronavirus shows why Trump’s healthcare policies are dangerous for all

Under existing rules, papers reporting federally funded research may be kept behind a publisher’s paywall for no longer than one year.

The change “would effectively nationalize the valuable American intellectual property that we produce and force us to give it away to the rest of the world for free,” according to a Dec. 18 letter to President Trump signed by 125 commercial publishers and professional societies.

“Going below the current 12 month ‘embargo’ would make it very difficult for most American publishers to invest in publishing these articles,” the letter asserted, adding that the the cost would then fall on taxpayers. The letter glossed over the fact, however, that taxpayers already shoulder much of the cost of publishing through subscription fees paid by institutions such as public universities.

The current crisis has demonstrated the value of open access to research, as well as the drawbacks of secrecy.

Researchers say they’ve benefited from an unparalleled level of data sharing about the novel virus. “This has gone on at a breakneck pace,” Schekman says.

The bitter battle between the University of California, a leading source of published research papers, and Elsevier, the world’s largest publisher of research papers, just got more bitter.

Information about the virus genome has been getting publicly released only days after samples were collected from infected persons, a pace tantamount to “real time,” Trevor Bedford, a biologist at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, said on the center’s website. That had allowed Bedford to determine that the virus was undergoing “sustained human-to-human” transmission after it moved from its animal hosts.

The rapid sharing of information has also sped the process of developing a vaccine for the virus, though experts warn that the necessity of perfecting and adequately testing the vaccine could mean a delay of a year or more in its availability.

The equivalent of crowd-sourcing data also allowed the scientific community to rapidly contradict a paper by Indian researchers and posted on the public database bioRxiv implying that the novel coronavirus had been concocted in a laboratory.

Analyses rebutting the findings appeared promptly and the authors withdrew their paper, though their claims were widely circulated by conspiracy theorists. BioRxiv placed a notice on its website cautioning that papers appearing there were not peer-reviewed and shouldn’t be treated as conclusive.

Government agencies are still trying to control information about the outbreak, an impulse that contributes to confusion rather than clarity. China’s clampdown on information about the original outbreak in Hubei province delayed word about the emerging crisis possibly for weeks. That hampered the global response and raised doubts about Chinese data that still exists.

In the U.S., the Trump administration also has directed that official statements about the crisis be funneled through the office of Vice President Mike Pence, who has been designated the head of the government’s COVID-19 response. President Trump, however, has repeatedly made statements about the crisis that have been contradicted by other officials.

Appearances on last Sunday’s political talk shows by Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease and one of the nation’s best known and most credible public health officials, were canceled at Pence’s directive, according to Rep. John Garamendi (D-Walnut Grove).

Garamendi says Fauci told him he had been directed not to do the interviews, but denied he had been “muzzled.” Fauci did appear with Pence and other public health officials at a White House briefing on Monday.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.