Column: Trump loses in court again on work rules for Medicaid

President Trump’s effort to impose work requirements on Medicaid recipients suffered another blow Friday with a harshly worded rejection by a federal appeals court in Washington.

The three-judge panel unanimously rejected the approval by Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar of a Medicaid work requirement in Arkansas, deriding Azar’s rationale as “not a hallmark of reasoned decision-making.”

The decision was written by Judge David B. Sentelle, a Reagan appointee to the court. He was joined by Cornelia Pillard, an Obama appointee, and Harry T. Edwards, a Carter appointee.

Nodding to concerns raised by commenters only to dismiss them in a conclusory manner is not a hallmark of reasoned decision-making.

— U.S. Appeals Judge David Sentelle

The judges upheld 2018 and 2019 rulings by federal Judge James E. Boasberg of the District of Columbia overturning the Arkansas rules and blocking work requirements that were poised to be implemented in Kentucky.

No judges have upheld work requirements for Medicaid thus far, underscoring the role of the federal courts in pushing back against Trump policies.

In the face of the judicial distaste for Medicaid work rules, as well as indications that they can result in thousands of low-income residents losing their health coverage, fail to promote job growth and raise the specter of prolonged and costly litigation, red states that had been considering such regulations have started to back away.

Red states that imposed Medicaid work requirements have discovered the policy doesn’t work and are reversing course.

Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear, a Democrat, canceled the state’s work requirements after taking office in January, reversing a policy contrived by his predecessor, conservative Republican Matt Bevin.

The administration hasn’t shown any signs of abandoning its push for work requirements, however. Trump’s latest budget proposal, issued Monday, proposes the imposition of Medicaid work rules nationwide. The proposal reflects the historic animosity of conservatives and Republicans toward Medicaid, the nation’s largest public health program.

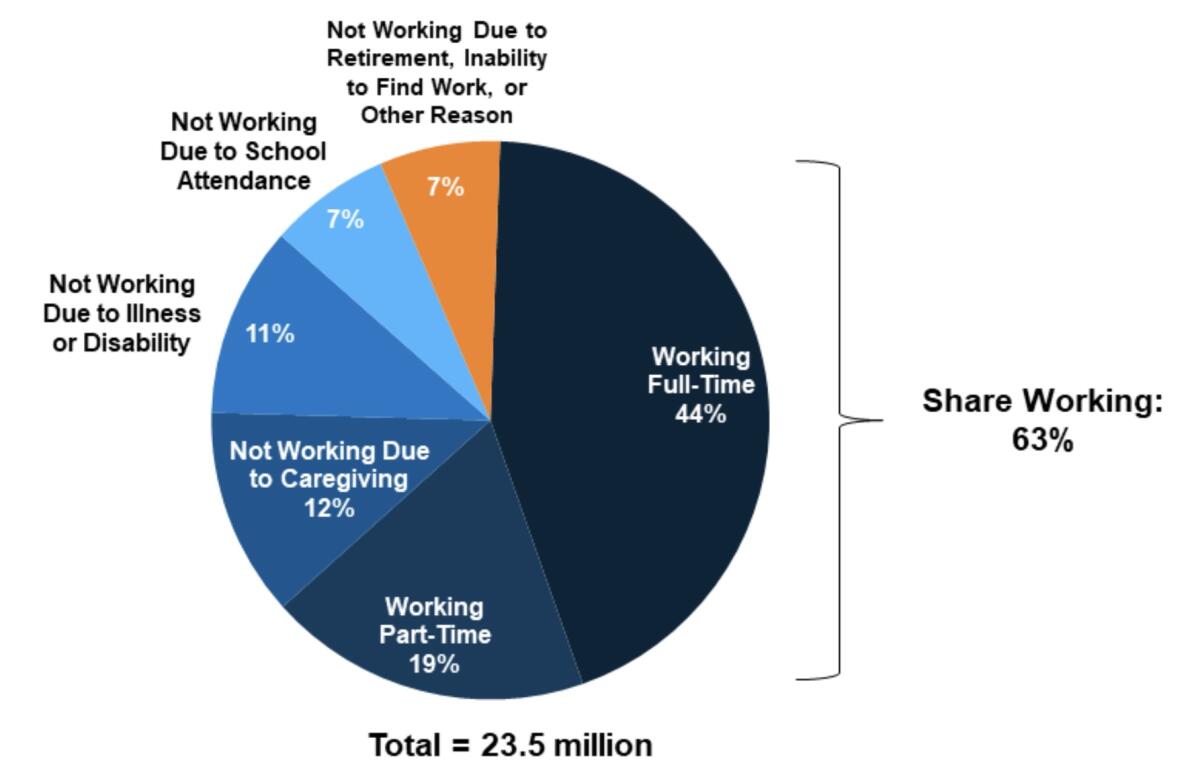

Medicaid advocates describe work requirements as nothing more than punitive provisions aimed chiefly at depriving low-income Americans of health coverage. Most Medicaid enrollees already are employed, and the vast majority of those who aren’t have good reasons — they’re students, elderly, caregivers at home or disabled.

Arkansas and Kentucky, like other states considering work requirements, designed a program that would create steep administrative barriers for enrollees.

In Arkansas, they would have to document their work or job search hours — a minimum of 80 hours a month was required to maintain Medicaid eligibility — and report them via a website that was often out of order and consistently inaccessible to those without a computer or internet connection.

In that state, Sentelle observed, more than 18,000 residents lost their coverage in only five months. That came to fully 25% of all those subject to the requirement.

Sentelle upbraided HHS Secretary Azar for approving the work rules on grounds that conflicted with Medicaid’s explicit statutory goals. Congress specifically dictated that Medicaid is aimed at providing health coverage for low-income households that can’t afford it on their own.

The contest for worst Cabinet member of the Trump administration is what we might call “competitive.”

Azar, in approving the work rules, rationalized them as likely to improve “health outcomes,” give enrollees an incentive to “engage in their own healthcare” and transition enrollees away from government benefits through financial independence.

Sentelle acknowledged that these are laudable goals, but don’t happen to be the goals of Medicaid. Although the government does have latitude in waiving some Medicaid mandates upon states’ requests, the waivers must “assist in promoting the objectives of Medicaid.”

The work rules failed that test, Sentelle wrote. “When Congress wants to pursue additional objectives within a social welfare program, it says so in the text.” Congress didn’t do so for Medicaid.

The most important shortcoming of Azar’s approval, Sentelle wrote, was that he didn’t consider the prospects that Medicaid enrollees would lose their coverage. That failure made Azar’s approval “arbitrary and capricious,” which is grounds for overruling any government regulatory action.

Indeed, Azar’s response to public concerns about disenrollments was dismissive. “Nodding to concerns raised by commenters only to dismiss them in a conclusory manner,” Sentelle wrote, “is not a hallmark of reasoned decision-making.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.