Column: Money-losing Tesla’s stock defies gravity, but a hard crash could be ahead

Relying on the dodge that I’m never wrong about the stock market, but my timing is sometimes off, I am willing to state that Tesla stock today is ridiculously overvalued.

The shares closed on Monday at $780 in Nasdaq trading. That’s a gain of nearly 20% on the day, and 86.45% since Dec. 31. All this has happened essentially on no news.

Oh, sure, the company issued its fourth-quarter and year-end 2019 results on Tuesday, and to hear Chief Executive Elon Musk and Tesla fans crow, you’d think they were spectacular.

‘The market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.’

— Attributed to John Maynard Keynes

The company cited $359 million in operating income and $105 million in net income for the quarter, which it categorized as “profitability,” an increase of $930 million in cash and cash equivalents, and “strong demand for our products.”

Not a few securities analysts on Wall Street have come around on Tesla after expressing long-term doubts. Dan Ives of Wedbush, for instance, forecast a price of $1,000 per share last Thursday as the “long-term bull case scenario” and placed his own target of $710 on the stock, though curiously he maintained a “neutral” rating — if he really thought there was a gain of a further 12% in the shares from their opening price Thursday, why not advise clients to “buy”? (Given Monday’s run-up, he almost looked like the soul of pessimism.)

As justification for the price surge, some on Wall Street pointed to Argus analyst Bill Selesky, who raised his target price on Tesla to $808 from $556, which sounds a bit like chasing a self-fulfilling prophecy. Dyed-in-the-wool Tesla bull Catherine Wood of ARK Investment Management, who just last week was forecasting a price of $6,000 for Tesla in five years, raised her projection over the weekend to $7,000 in 2024.

The bear-market argument for Tesla shares is still out there, but there’s no question that short sellers have taken it in, well, the shorts. Bloomberg BusinessWeek made them its cover guys and gals of its Jan. 27 issue, headlined: “Bye, Haters: Short sellers despise Elon Musk, but Tesla’s stock is climbing — and costing the skeptics billions.”

It’s certainly proper to wonder what’s driving Tesla shares higher. Tesla’s market capitalization (stock price times shares outstanding) is more than $115 billion at its current price, nearly 40% higher than those of General Motors and Ford put together. But they sell a lot more cars than Tesla. U.S. sales in 2019 were 2.87 million vehicles for GM, 2.4 million for Ford and about 195,000 for Tesla. In global sales, Tesla barely ranks at all.

A curious, not to say bizarre, line of chatter has emerged in connection with the fight between Tesla Chief Executive Elon Musk and the Securities and Exchange Commission.

What about that “profitability”? Investors might want to take a closer look at Tesla’s disclosures. In the fourth quarter, for example, Tesla reported net income on a GAAP basis of $105 million on revenue of $6.4 billion. That is, a quarterly profit according to generally accepted accounting principles, which is the standard used by serious investors.

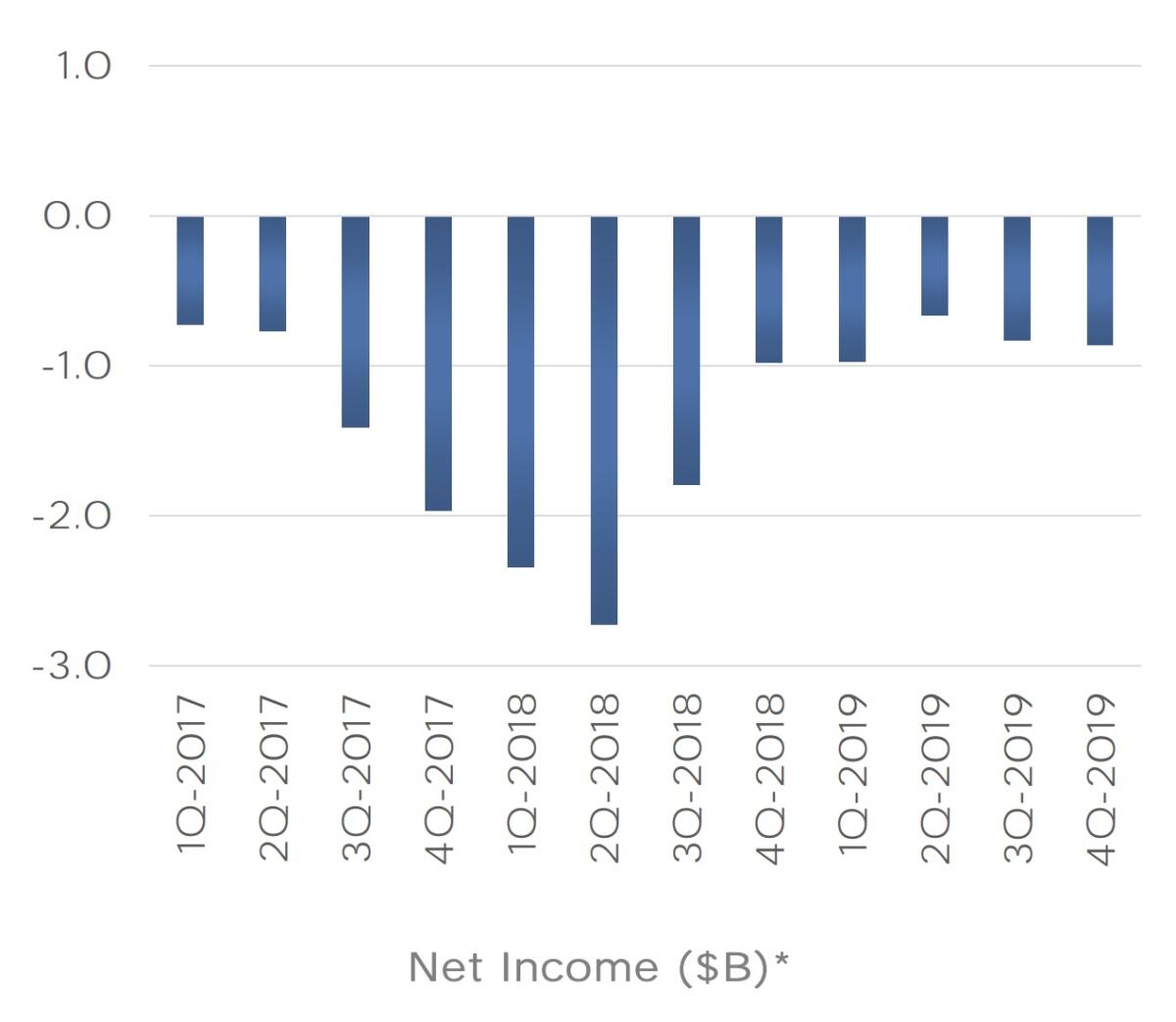

But the company also attributed $133 million of its revenue to sales of regulatory credits. Those are government-issued credits that can be sold on the open market to automakers that can’t otherwise meet emission or mileage standards. Without those sales, Tesla would have been in the red for the fourth quarter. Indeed, over the last four quarters, a period in which Tesla reported an annual loss of $862 million, the loss would have been more than $1.4 billion.

To put it another way, Tesla arguably still is not turning a profit from selling cars. As its own figures show, the company hasn’t recorded a profit over any four straight quarters in 2017-19.

So what’s driving its shares higher? It’s hard to see Tesla as anything but a quintessential “story stock.” That’s a company that attracts investors because they buy into factors that are divorced from actual profit-and-loss results or even reasonable projections. Indeed, Liam Denning of Bloomberg observed this week that the stock price is “pretty much divorced from any reasonable underlying math.”

Denning said a mouthful. Consider the traditional measure of a security’s value — its price/earnings multiple, or the relationship between a company’s profit and its share price. But if it matched the 27.96 average P/E multiple of the Nasdaq 100 index, of which it’s a component, it would have to record a profit of $4.9 billion to justify its current share price.

If it matched the P/E of the Standard & Poor’s 500 index, which is 24.27, it would have to record an annual profit of $5.6 billion to justify its current price. Tesla’s not on the S&P 500 because it never has recorded an annual profit. That’s also why it doesn’t have a P/E multiple.

Many Wall Street analysts are still skeptical about the Tesla story, which appears to irk Musk no end; analysts at Barclays and Bernstein called Tesla stock overstretched at current prices last week even after its earnings report beat Street estimates. During a conference call after the company’s earnings release Thursday, he dismissed negative judgments from Wall Street.

“I do think that a lot of retail investors actually have a deeper and more accurate insights than many of the big institutional investors and certainly a better insight than many of the analysts,” he said. “It seems like if people really looked at ... what some of the smart — smaller retail investors predicted about the future of Tesla ... you’d probably get the highest accuracy and remarkable insight from some of those predictions.”

The stories told about story stocks often involve a company’s entry into a novel but theoretically lucrative market (such as electric vehicles), a proprietary technology (such as EV batteries), or a visionary leader who sees things others miss (say, Elon Musk). Sometimes the story is that everyone else is gaga over a stock, so you’d better get in while the getting is good. (These are sometimes also known as a “momentum stocks.”)

The story being told about Tesla comes out of the mouth of Musk. He talks a spectacularly alluring game of a world populated by autonomous cars running Tesla hardware and software. There’s scarcely a quarter in which he doesn’t hold out the prospect of a new Tesla model — a sportster, a pickup, a heavy-duty truck — or an advance in the company’s global manufacturing capacity or technology.

Yet one would think that investors had become inured to Musk’s projections, since he’s had a record of overpromising and underdelivering. The company projected in its latest earnings release that “its vehicle deliveries should comfortably exceed 500,000 units” in 2020. But as Jemima Kelly observes in the Financial Times, in May 2016, Musk promised production of 500,000 Teslas in 2018, and in February 2019 he promised production of 500,000 Teslas by the end of the year. (He backed off the latter forecast within hours, changing it to 400,000 and saying he meant to say production of 500,000 at an annual rate by the end of 2019.)

Elon Musk finally found a way to turn his Wall Street fans into doubters.

As my colleague Russ Mitchell reported, total Tesla deliveries in 2019 came to 367,000.

The drawbacks of story and momentum stocks is that the story can be punctured by a single well-placed needle, the momentum may move on to another darling, or investors may suddenly recognize that the price has moved ahead of even the wildest expectations.

As it happens, the stock market boneyard, or at least its ICU, is littered with such stocks. For instance, Uber went public last March amid expectations that it would be worth as much as $120 billion. (We expressed skepticism even at a prior private market valuation of $70 billion.) As of Thursday’s close, it’s worth $62.5 billion, and even that may well reflect the residue of optimism.

It’s often difficult to forecast what might puncture an inflated story stock. The dot-com bust of 1999-2000 brought down a bunch of highfliers. Apple, for example, soared from a split-adjusted 50 cents in late 1997 to $5 in March 2000, a tenfold gain, then plunged 80% to about $1 in the dot-com bust. (Hat tip to my colleague Jim Peltz for the memory.)

Nothing about WeWork looks normal, and Wall Street may finally be waking up

Apple remade itself and recovered, but its shares lost about 12%, or some $60 billion, in a single day in late January 2013 when it reported disappointing sales for its iPhone. Facebook lost nearly 23%, or about $120 billion in market cap, on July 26, 2018, when it reported disappointing quarterly results and forecast that its storied future might not be as glittery as expected.

Going further back, there was the case of Roswell Pettibone Flower, a former New York governor described as “the bull market incarnate.” Investors hung on his every word, buying on his say-so just as later generations would follow the investment choices of Warren Buffett.

In 1899 Flower had driven up shares of the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Co. by placing the target price at $75 when it was trading at $20, at $125 when it had reached $50, and eventually at $135. At that moment, however, he was struck down by a heart attack. The air instantly rushed out of all the “Flower stocks,” threatening to take down the entire market until J.P. Morgan and other leading bankers stepped in with millions in capital to stem the downturn.

Could Tesla continue to rise indefinitely? Of course. As irrational as the price seems today, based on actual sales and earnings, there may be more madness ahead. A favored stock market adage is often attributed to John Maynard Keynes as a warning not to bet against the mob.

“The market can stay irrational,” Keynes is said to have counseled, “longer than you can stay solvent.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.