Column: This government price-fixing case makes the tuna industry sound like the mafia

Speaking as a lifelong aficionado of the tuna fish sandwich on rye, I was relieved to learn that Bumble Bee’s Nov. 21 bankruptcy filing wouldn’t mean the eradication of the brand from store shelves — it would merely come under new ownership.

Yet there’s much more to it than that. The bankruptcy filing is an outgrowth of a price-fixing case that makes tuna processing seem a lot wilder and more colorful on dry land than it is at sea.

In fact, judging from the federal allegations, the guilty pleas filed by all three major tuna processing companies and several of their executives, and other documents, a lot went on in this industry that wouldn’t be out of place in a Martin Scorsese movie.

Rather than focus on innovation and growth, the three major brands have fought an ‘unwinnable’ war to steal shares from one another.

— Tuna executive Christopher Lischewski warns against price competition in canned tuna in 1999

There are secret meetings to plot criminal strategies, participants turning state’s evidence to cut a better plea deal than their co-conspirators, even the allegation of a sotto voce threat delivered with a brotherly hand on the shoulder of a would-be witness.

The three brands involved are household names: Bumble Bee, StarKist and Chicken of the Sea. The first two have pleaded guilty to criminal price-fixing, agreeing to fines of $25 million and $100 million, respectively. Chicken of the Sea has been awarded amnesty for blowing the whistle on the two others. (Bumble Bee and Chicken of the Sea are based in San Diego, StarKist in Pittsburgh.)

Bumble Bee was assessed the lower fine because it successfully pleaded to prosecutors that any higher figure would put it out of business.

As I’ve reported previously, the government’s price-fixing case began with routine antitrust scrutiny of a proposed $1.5-billion merger between Bumble Bee and Chicken of the Sea. The merger, announced in 2014, would have created a canned tuna giant commanding nearly half of the U.S. market, swamping StarKist, which at the time was the No.1 brand with 34.6%.

Column: The Bumble Bee tuna price-fixing case could point to the future of white-collar prosecutions

When the roll call is sounded of business deals that looked like a good idea at the time but went massively wrong, special notice should go to the merger of the tuna packagers Bumble Bee and Chicken of the Sea, announced in late 2014.

The Department of Justice turned thumbs down on the merger in 2015, but its announcement had an ominous tone. “The market is not functioning competitively today,” the agency said, “and further consolidation would only make things worse.” Reading between the lines, the department had found evidence of a price-fixing conspiracy.

Chicken of the Sea’s parent company, Thai Union Group, abandoned the merger and sang like a canary, knowing that under Justice Department protocols the first member of a conspiracy to turn on the others gets the sweet deal. Bumble Bee executives Walter Scott Cameron and Kenneth Worsham, and StarKist executive Stephen L. Hodge all subsequently pleaded guilty to federal price-fixing charges and agreed to cooperate with federal prosecutors.

That leads us to what may be the last federal loose end: the criminal prosecution of former Bumble Bee Chief Executive Christopher Lischewski. Testimony in Lischewski’s trial wrapped up on Tuesday in federal court in San Francisco. Closing statements are scheduled for Monday, after which the case will go to the jury. Lischewski was a major prosecution target because he was one of the most respected and influential executives in the tuna canning industry, and also because, by the government’s reckoning, he was a mastermind of the scheme.

Lischewski’s defense boils down to two points. One is that what the government depicts as illegal price fixing is in fact perfectly legal marketing arrangements among major players in a single industry. The second is that even if something illegal was going on, it was done by underlings behind Lischewski’s back.

According to a report from the courtroom, Lischewski testified at trial that he was “shocked” when he heard that Worsham and Cameron had filed guilty pleas. He also denied Cameron’s testimony about a meeting in 2015 at which Cameron asked him about the progress of the Justice Department investigation and that Lischewski put his arm around Cameron’s shoulder and said he shouldn’t worry “as long as you and Kenny don’t [screw] it up.” Lischewski’s attorney didn’t respond to my request for comment.

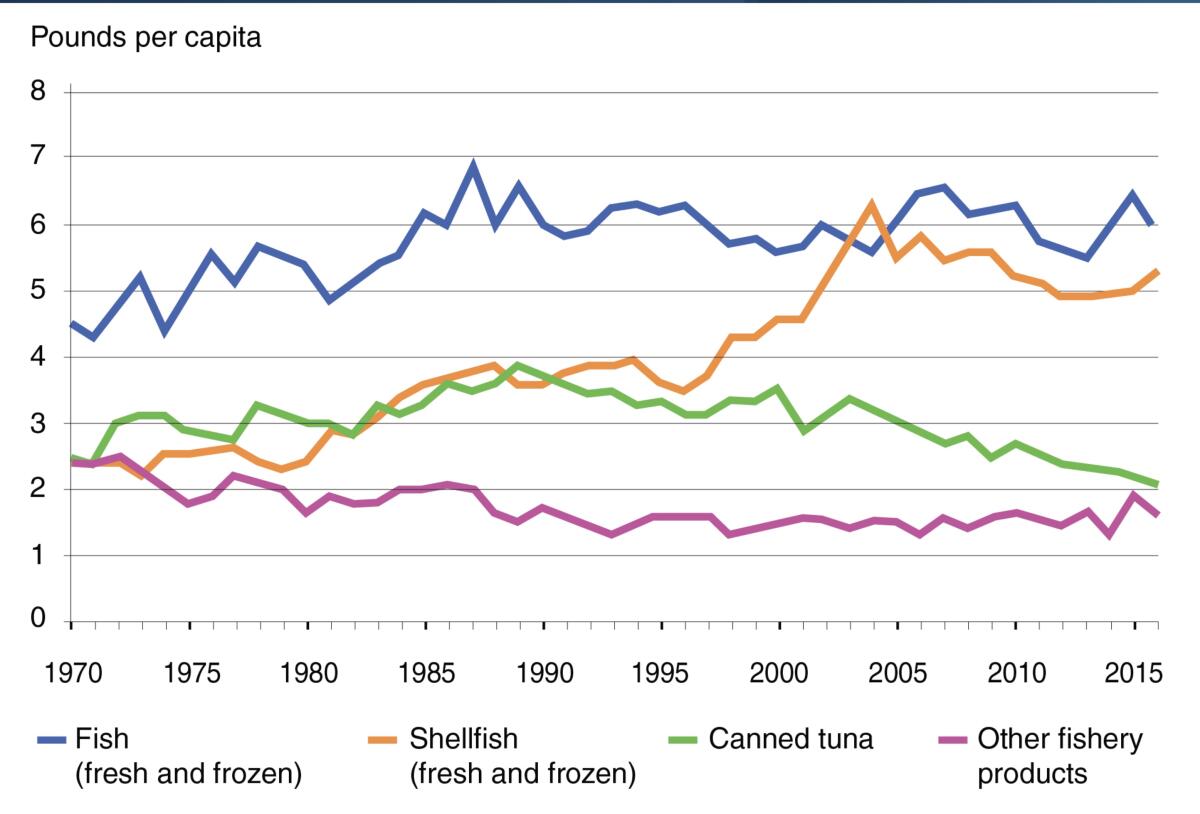

Whatever role Lischewski may have played in the price-fixing scheme admitted by his own company and its two co-conspirators, the scheme seems to have arisen from the companies’ perception that they faced an existential threat. U.S. consumption of canned tuna had experienced a vertigo-inducing slide from 3.9 pounds per capita in 1989 to less than 3 pounds in 2000 (it would fall to just over 2 pounds by 2016) while consumption of other seafood such as shellfish was either stable or rising.

Experts haven’t been able to put their finger on the reason for the decline of canned tuna. Some point to fears of mercury contamination in fatty fish like tuna, others to public concerns about dolphin deaths resulting from tuna fishing techniques. But the culprit may simply have been the greater availability of fresh and fresh-frozen alternatives to canned fish.

Heather Sears has been fishing for salmon out of this unassuming coastal community for nearly two decades.

Lischewski sounded an early warning at an industry conference in 1999, upbraiding industry leaders for a relentless battle for market share that had discounted prices by as much as 31%. “Rather than focus on innovation and growth,” he said, according to a lawsuit filed by a coalition of tuna wholesalers and distributors, “the three major brands have fought an ‘unwinnable’ war to steal shares from one another.” He estimated the profit loss at $200 million a year.

When the decline in consumption continued, Bumble Bee, StarKist and Chicken of the Sea took several steps to shore up profits. They shrank the size of their cans without a commensurate price reduction. The 7-ounce cans that were the standard as recently as the 1980s gave way to 6-ounce cans, and a couple of years ago to 5-ounce cans. In 2012 the three companies paid $3.3 million to settle accusations by three California counties that they had short-weighted their cans by filling them with more water and less meat than the labels indicated. They didn’t admit guilt.

In the charges filed against the companies in 2016 and 2017, the government asserted that they went further by actively conspiring to fix prices from late 2010 through 2013 at repeated meetings among high-level executives at industry conferences and meetings at a San Diego restaurant. Wholesalers, retailers and other plaintiffs who filed scores of civil lawsuits alleged the plot may have continued longer.

No one has put a number on how much the companies allegedly squeezed from consumers through colluding. U.S. canned tuna sales, however, come to more than $1.7 billion a year.

The government pointed to several joint marketing schemes that either predated or occurred during the criminal conspiracy. These included a joint decision in 2008 to downsize the cans to 5 ounces, a “Tuna the Wonderfish” promotional campaign resembling the dairy industry’s “Got Milk” ad campaign and an agreement between Bumble Bee and Chicken of the Sea to share each other’s packing facilities in Georgia and Santa Fe Springs.

Lischewski argued that these arrangements weren’t illegal in themselves. The government didn’t disagree, but asserted that they provided opportunities for the executives to build “a closer relationship that eventually led to discussions and agreements regarding pricing.”

Wholesalers and retailers say they sensed something strange about canned tuna prices even before the feds took action. Walmart, in a lawsuit filed in October 2016, observed that the supply of tuna had increased sharply over the years due to innovations in fishing technology while demand was falling. That should have driven canned tuna prices down, but instead they rose. From 2008 through 2014 — including the period that the government says the price-fixing scheme was in full cry — Chicken of the Sea’s parent company more than doubled its profit to $140 million from $61 million, Walmart pointed out.

The parent attributed the increase in part to “more rational U.S. market competition.” Walmart’s gloss: “The ‘more rational’ competition was not competition at all; it was collusion.” In early 2012, for instance, the three companies announced virtually identical price increases within days of one another.

In its bankruptcy filing, Bumble Bee says that despite the indulgence of prosecutors, it’s still hobbled by the criminal fine (on which it still owes about $17 million) as well as the threat of damages in the civil lawsuits. In conjunction with the filing, it announced a takeover bid for about $930 million by FCF, a Taiwan fishing brokerage that provides Bumble Bee with almost all its high-quality albacore tuna and most of its light-meat tuna. (FCF is playing the role of a “stalking horse,” meaning that it could be outbid by another buyer.)

FCF’s offer would cover Bumble Bee’s assets, the $17 million owed to the government, and about $640 million in outstanding debt. Notably, it doesn’t provide for plaintiffs’ damages. Where that leaves the plaintiffs is unclear. “We intend to be active in the bankruptcy process to ensure that it is fair for all creditors,” Christopher Lebsock, an attorney for the plaintiffs, told me by email. He noted that the terms of the takeover deal would have given FCF preferential treatment over the other creditors, since Bumble Bee proposed paying FCF’s entire $51-million pre-bankrupcty claim. Bankruptcy Judge Laurie Selber Silverstein issued an order Tuesday rejecting that payment.

What’s most unclear is where the canned tuna business goes from here. The price-fixing scheme looks to have been exactly the wrong strategy, as the criminal fines and other fallout have made things only tougher for the participants.

Bumble Bee’s operating earnings, according to a statement filed in Bankruptcy Court by its chief financial officer, Kent McNeil, declined by 20% from 2015 to 2018 — a “negative trend” that placed the company at risk of defaulting on its loans. The decline in the company’s fortunes was plainly secular. Something was fishy in the tuna world, but the signs of rot ran even deeper.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.