They turn ’49 Mercurys and Shelby Cobras into EVs, one Tesla carcass at a time

In a garage near South Los Angeles, metal fabricator Greg Abbott fits battery packs borrowed from a decommissioned Fiat 500E under the hood of a 1965 Mustang.

In Oceanside, Calif., former AAMCO mechanic Matthew Hauber combines the suspension system and battery packs from a totaled Tesla to make an 800-horsepower, all-wheel-drive Shelby Cobra.

In an unlikely marriage of classic car culture and green technology, sophisticated hot-rodders — mostly men, mostly Californians — are cannibalizing crashed electric cars and using their batteries to create electrified sports cars and muscle cars.

As comfortable wielding an ohmmeter as a spark-plug wrench, they are expanding the automotive world’s consciousness about what can be done in the electric-vehicle space — and making good money doing it. Their price can run from $30,000 for a do-it-yourself conversion kit for a VW Bug to several hundred thousand dollars for a fully customized, up-from-the-tires EV overhaul.

“These guys are taking drivetrains out of Teslas and Nissan Leafs and putting them in all kinds of vehicles,” said Gordon McCall, founder of the Quail Motorsports Gathering in Carmel, Calif., one of the country’s most respected annual automotive events. “They’re hot-rodding electric cars just like their grandfathers did with 1932 Fords.”

The EV classics are gaining stature on the custom car circuit. August’s Quail event featured “A Tribute to the Electric Car Movement.” On the fairway were a VW microbus conversion and a battery-powered 1949 Mercury, which took the top prize in the Quail’s first-ever electric car class.

Hauber became interested in electric vehicles after seeing the 2007 documentary “Who Killed the Electric Car?” about the demise of GM’s 1990s-era EV1. He got a job working on EV pioneer Jack Rickard’s popular electric vehicle webcast. Soon he was building electric cars on his own.

Abbott started early, too. Sometime around 2004 the artist, furniture builder and metal fabricator, who goes by the moniker Reverend Gadget, converted a Triumph Spitfire into an electric vehicle, using old-fashioned lead-acid batteries that were heavy and hard to control. Friends began asking him to build them electric cars, too.

The process was tedious, and the results were undependable. Standing in his cramped Florence-area workshop alongside a mid-electrification Porsche Speedster, a classic Volvo station wagon and a rusting 1947 Ford pickup, Abbott said, “They were like rolling science experiments, and you had to be a tinkerer to own one.”

Sociologists looking for new evidence of conspicuous consumption — look no further.

Salvation came in the form of Elon Musk and Tesla. Pouring massive resources into batteries and battery management, the billionaire entrepreneur started selling increasingly large numbers of electric cars powered by lithium-ion energy packs that were powerful, rechargeable and reliable.

When Tesla owners crashed their Tesla Model S sedans and Model X SUVs, and the cars wound up as insurance write-offs, EV scavengers came running. They would scour local junkyards for the damaged cars and pay, in the early days, only a few thousand dollars for their undamaged battery clusters.

That increased the power and range of the custom electrified vehicles and made them a lot easier to own and operate. “Then you could just hand the keys to someone, to anyone, and say, ‘Drive it until it runs out of electricity and then plug it in,’” Hauber said.

Interest in retro EVs has accelerated in recent years.

In 2013, former advertising executive Dave Benardo and his wife and partner Bonnie Rodgers traded San Francisco for San Diego to pursue their passionate interest in vintage Volkswagens. When they electrified a Beetle and documented the process online, customers came calling. To date, their Zelectric Motors has converted about 30 Bugs, Karmann Ghias, microbuses and VW Things into battery-powered runabouts.

They found that putting maintenance-free electric drivetrains into vintage vehicles eliminated a lot of mechanical babysitting that classic cars demand of their owners. “There are people who are in love with the design of these classics, but they don’t want to do the wrenching on them,” Benardo said. “They just want to spend more time driving.”

For one customer, Benardo recently electrified a 1973 Porsche 911 S. The car looks exactly as it did when it was new, except that under the hood an electric motor that makes 240 horsepower has replaced an engine that made 180.

“Now it’s just a question of going faster in an old car,” Benardo said.

Sometimes, too fast. The 800-horsepower Shelby Cobra that Hauber made for commercial TV lighting technician Don Swadley of El Cajon, Calif., was so powerful as to be virtually undrivable.

“Even with the motor tuned down, we couldn’t get any traction control,” Swadley said. “At 50 miles per hour, you’d put your foot on the pedal and the car would go completely sideways.”

Hauber’s solution: Make the Shelby more like a Tesla by adding a Tesla drivetrain and suspension system, with the Model S’s standard P85 motor in the back and an upgraded Tesla P100D motor up front. “It’s 2,600 pounds lighter than a Tesla, and it’s absolutely faster than any Tesla on the road,” Swadley said. “Now I can go down the road with the wind messing up my hair and out-accelerate anything and not be killing any trees.”

Graphic designer Thomas Almodovar of Playa del Rey said he was thinking of buying an electric car, in part to help the environment. Then he thought, “It creates a lot of pollution to make a new car. But if you buy a used one and convert it, you’re not polluting at all.”

Almodovar paid a local garage $2,500 for a 1979 MG that had come to the end of its mechanical life. Then he spent $19,000 to have Abbott modify it. The result: A silent-running convertible sports car that has amazing torque and a 60-mile range.

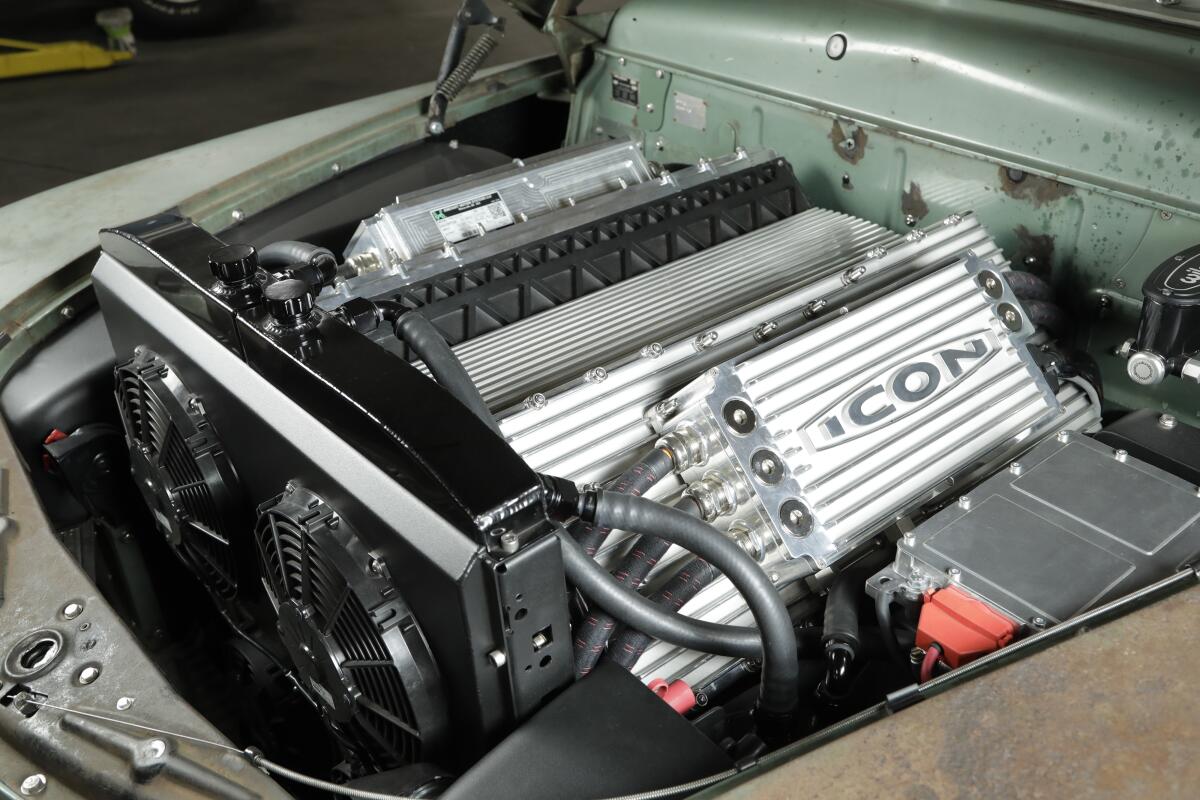

In the case of Jonathan Ward and his Icon workshop in Chatsworth, the classic cars are really classic.

The car builder and former Toyota designer, who made his name turning shells of gas-powered Toyota Land Cruisers, Ford Broncos and Chevy pickup trucks into modern street racers, spent three years and thousands of R&D hours electrifying the Quail-winning 1949 Mercury for a loyal customer. When he was done, he’d built a 400-horsepower EV bomb powered by Tesla batteries and capable of being recharged using any of the charging systems currently in use, including Tesla’s Superchargers, he said.

With a top speed of 120 mph and a range of 150 to 200 miles, the vehicle offers the beauty of a classic Detroit cruiser with modern attributes such as power steering, air conditioning and a Bluetooth connection.

Most of the retro-EV customizers power their vehicles with batteries from wrecked Model S, Fiat 500 or Nissan Leaf cars that have less than 20,000 miles on them. They hold up well, the builders said, and are likely to last well past the 100,000-mile mark typically exceeded by Teslas.

“I’ve never had one fail. Ever. Not one,” Hauber said.

The upside, for some customers, is ease of ownership. Like the EVs built by major manufacturers, these Franken-vehicles have far fewer moving parts than gas-powered cars and need little service attention. If the batteries or other parts need replacement or the owners want to upgrade to more powerful motors, the cars can be serviced by the builders.

Tesla — which did not respond to requests for comments — has actively discouraged the use of salvaged vehicles or parts, and has been accused of disabling the software on cars it has written off. It took creative work by dedicated hackers to write third-party code that would allow builders to remove the batteries and use them properly, Icon’s Ward said.

The downside, for many, will be the cost. Today, Hauber and other builders say, Tesla batteries pulled from wrecked cars cost them $16,000 and up — just for the batteries. That leaves aside the cost of the AC motor, controllers and other parts. And the price is going up as competition among EV customizers increases.

It used to be that a company would have only one supercar ever — or at most, one per year — now it seems they’re whipping them up as fast as possible.

Hauber’s Stealth EV will sell a conversion kit for a VW Bug for about $30,000. If his shop installs it, add $15,000 or more. If it’s a car “for the performance horsepower enthusiast with a classic muscle car where the buyer wants to go all out,” Hauber said, figure $130,000 and up — added to whatever the host car cost in the first place.

In Chatsworth, the wiry, bespectacled Ward declines to say what he is charging the new owner of the 1949 Mercury, though he says a similar project went out the door at $500,000. When a valued repeat customer decided he wanted his 1963 Ferrari GTE 250 restored and made electric, Ward says he told him, “I can’t even begin to guess how long it will take or how much it will cost.” The customer gave him the go-ahead anyway, on a car probably valued at more than $500,000 — before the conversion.

Costs could begin to come down on some machines as more Teslas enter the market. As many as 700,000 Teslas may be currently on U.S. roads. In mid-October the company reported it sold 97,000 vehicles in the third quarter.

Some of those cars, unfortunately, are going to crash and wind up in salvage yards. But some of their batteries will have a second life powering custom EVs.

When director James Mangold’s new movie “Ford v Ferrari” hits theaters Nov. 15, car nuts may find themselves asking where the filmmakers found all those classic Carroll Shelby race cars from the 1960s, which sell for millions of dollars when they become available.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.