Wine country is struggling to attract visitors. Fires and blackouts aren’t helping

Before it burned to the ground during the 2017 wildfires, the tasting room and headquarters for the Signorello Estate winery in Napa was an ivy-covered, two-story edifice on a hillside, overlooking an expanse of oak trees and vineyards.

Although a new tasting room and adjacent business offices have yet to be built, the winery has continued to grow grapes, make wine in an off-site facility and host wine tastings under nearby tents and in a mobile facility.

“The silver lining is we lost some buildings but we didn’t lose any vines,” said Ray Signorello Jr., proprietor of Signorello Estate. “The grapes and winemaking has been largely uninterrupted.”

But like many of his fellow winemakers, shopkeepers and restaurateurs who survived the 2017 wildfires in Napa and Sonoma counties, Signorello struggles to get the word out that one of the world’s premier winemaking regions remains open for business and eager to host visitors.

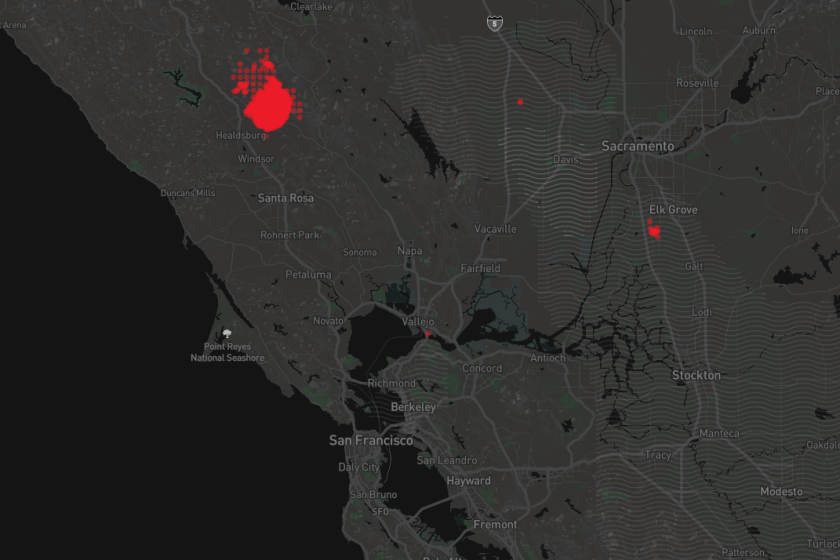

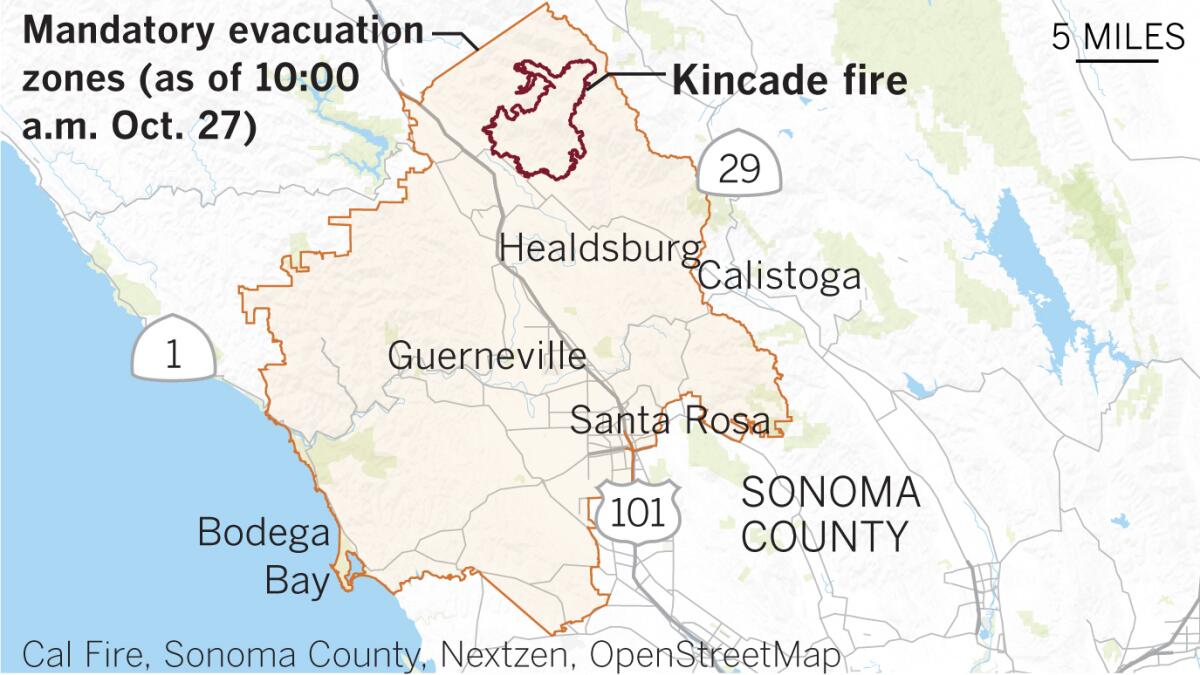

That effort has been hampered lately by a wildfire that broke out in northern Sonoma County last week and by the decision by Pacific Gas & Electric to shut off power in the region intermittently during high-wind days to help prevent another fire disaster.

The stakes are high.

In both Napa and Sonoma counties, tourism ranks among the top industries, with more than 40,000 combined jobs directly dependent on visitors. Spending by tourists generated more than $4 billion to the economies of the two counties last year, with most of the money spent on lodging.

In Napa County, tourism ranks second only to the wine industry as a top employer.

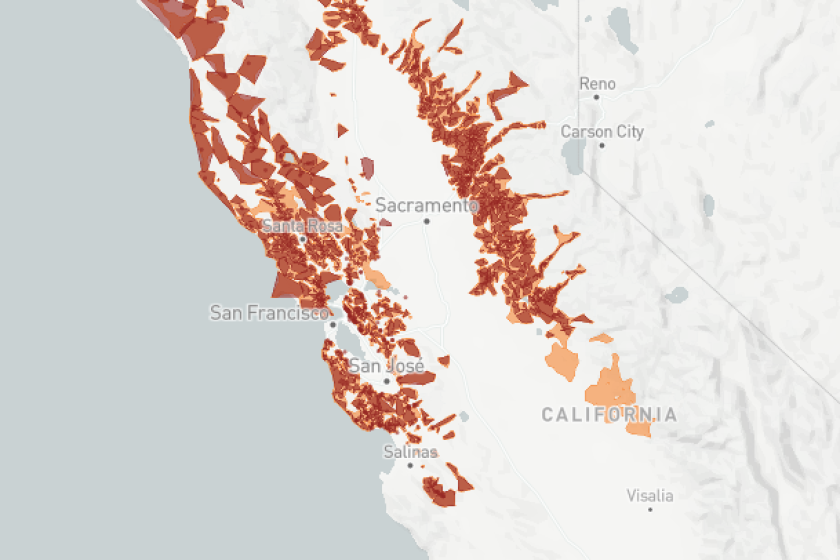

The challenge, local tourism leaders say, has been crafting a promotional message that encourages visitors to return without reminding them about the current fire threat or the 2017 conflagration that killed at least 43 people, destroyed about 8,400 buildings and charred more than 245,000 acres.

“We have been trying to showcase what a beautiful spot this is,” said Linsey Gallagher, chief executive of Visit Napa Valley, the tourism organization for Napa County.

The 2017 fires made headlines and generated dramatic television footage across the country, but fewer than 20 of the 900 or so wineries in Napa and Sonoma counties suffered significant damage. Most restaurants, shops and hotels also survived unscathed and many of those that were damaged or destroyed have been rebuilt.

The latest visitation numbers and hotel occupancy rates suggest that some areas of the wine region have rebounded from the disaster, while others continue to suffer.

Napa County welcomed 3.8 million visitors in 2018, an 8.9% increase compared with 2016, while visitor spending rose 15.9% to $2.2 billion, according to an economic impact study released in May. Gallagher said her organization has not collected economic data for 2019 but anecdotal evidence suggests the business climate remains strong.

“That tells us that people are staying longer and spending more,” she said.

In neighboring Sonoma County, the tourism industry has suffered. Hotel occupancy rates in the county are about 4% below the levels of 2018 and retail sales figures have dropped about 5% in the same period, said Claudia Vecchio, chief executive of the Sonoma County Tourism agency.

“I believe we are still impacted by those fires,” she said.

As a result, Sonoma has had to rely on a more direct message.

Before the 2017 fires, Sonoma County promoted the natural beauty, food and relaxed atmosphere of the region, with the campaign tag line “Life opens up.” Now, the region is turning to less-subtle appeals, with promotions that list visitation packages, she said.

The organization is conducting a survey of potential visitors throughout the state to gauge what type of new marketing campaign Sonoma County should launch in the coming months.

“That will be telling, for sure,” she said.

Crisis management experts suggest local tourism leaders in the wine country should consider embracing the 2017 fire disaster as a reason for tourists to visit.

Dan Hill, chief executive of Hill Impact, a crisis management firm in Washington, D.C., said the region could try to appeal to the charitable nature of tourists. He noted that was a primary reason why Puerto Rico has enjoyed an uptick in tourism in the two years after Hurricane Maria struck the island.

“People will go to that region because it has been devastated,” he said. “I can see a fraction of the public going specifically to help them recover.”

Napa County has no plans to try such a campaign, Gallagher said.

“That is not the direction we would be heading in,” she said. “Consumers need to move on from that and feel the safety of the destination.”

Winery owners and restaurateurs in both counties say they are sticking to advertising and social media campaigns that promote the positive elements of the region without hearkening to images of the fire.

The Kendall-Jackson Wine Estate and Gardens in Santa Rosa, which had lost no buildings or vineyards in the fire, has been promoting its “farm-to-table” dinner offering, plus a new boccie ball court and picnic areas.

Kristoffer Miller, the tasting room manager at Kendall-Jackson, acknowledges that sending out a positive message has been difficult, especially with PG&E shutting off power during windy days in hopes of preventing another wildfire.

“It does remind people of the fire and it makes people scared, and that is impactful to the business,” he said.

In Santa Rosa, Willi’s Wine Bar reopened in May in a new site after the previous location burned during the 2017 fire. Business has rebounded and about 70% of the previous staff has returned, said Terri Stark, who along with her husband, Mark, owns six restaurants in Santa Rosa and Healdsburg, both in Sonoma County.

The message to visitors and locals, Stark said, is “we are back and picking up where we left off.”

But she conceded that the power outages and the latest fires are making it difficult to stick with a positive message. “For me, moving on is the best coping mechanism,” Stark said.

At the Cardinale Winery in Oakville, visitation numbers have reached pre-fire levels, said Ross Anderson, the winery’s estate director. None of the vineyards were damaged in the 2017 fire, he said, but about a quarter of the grapes were lost because workers couldn’t get access to some of the vineyards.

Anderson said he is troubled that people still ask him about the 2017 fire, adding that he plans to focus on promoting his wines, not on past disasters.

At Signorello Estate, the fire that burned the headquarters and tasting facility miraculously spared the vineyards and the fermentation tanks.

Before the building was destroyed, it hosted wine tasting events and five-course lunches, whipped up by an in-house chef.

For Signorello, it is difficult to send a positive message to wine lovers when the winery can no longer host large groups or offer the same services as before.

“We used to host people on our property and had a chef and very nice hospitality experience on the property,” he said. “We lost the ability to have that.”

A timeline for rebuilding the destroyed facility is still uncertain, said Signorello, because of a backlog of rebuilding projects for construction contractors. But, he added, his workers were able to harvest nearly all the grapes in 2017 and the wines that resulted from that harvest are exceptional.

“We made some very good wine in 2017,” he said.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.