Landlords say state rent caps may force them to raise rents more frequently

Prominent landlord attorney Dennis Block stood before a crowd of more than 200 at an apartment owners trade show in Pasadena and, to laughs, boasted of having evicted “more tenants than anybody else on the planet Earth.”

Block said he was proud to enforce what he said America was built on: property rights. He then talked about the “scourge of this new statewide rent control that is coming up” and offered some ways that landlords could evade rules that as of Jan. 1 would cap annual increases for tenants at 5% plus inflation and require “just cause” to evict.

His advice? Quickly hand out no-fault eviction notices to tenants who pay low rent or make frivolous requests.

“You don’t have to feel bad about this,” he said Wednesday at the trade show for the Apartment Assn. of Greater Los Angeles, which represents landlords. “It’s not your fault, it’s the state legislators’ fault.”

Gov. Gavin Newsom is expected to sign Assembly Bill 1482 into law this month. And while supporters celebrate its potential to stanch the flow of people who are priced out of their communities or onto the streets, landlords are grappling with what it means for them.

The rent-cap law covers only buildings older than 15 years and applies to single-family homes only if they are owned by corporations or other institutional investors. It expires in 2030 and won’t override stricter rent control ordinances in places such as Los Angeles and San Francisco.

How property owners react will go a long way to determining how effective the bill is in providing greater protection to tenants in California’s unaffordable housing markets.

“Merely making a passive investment in rental property has become a huge burden and risk, so owners tend to gravitate to what people like Dennis have to say in hopes that there may be some relief out there,” said Daniel Yukelson, executive director of the apartment association. “The more the government tries to corner rental property owners, the more they will, by nature, look for ways to get around those regulations in order to protect the large investments.”

Today, landlords of non-controlled units can generally tell long-term tenants to leave in 60 days for no stated reason, as long as doing so wouldn’t break a lease. Starting Jan. 1, landlords covered by the bill will need just cause such as nonpayment of rent or damage to a unit to remove renters who have lived in their units at least a year.

Block noted that any recent rent increase above the coming cap must be canceled in January. But no similar provision exists for the new just-cause eviction rules. As a result, he explained, it’s possible to get rid of low-paying tenants and significantly raise rents — landlords can charge what they want for vacant units — as long as the notice to vacate expires before Jan. 1.

The controversial attorney made a similar pitch at another recent trade show, and in email blasts and social media posts.

Yukelson said he doesn’t recommend quickly evicting tenants to get around the new law and said that prospect “looks bad for” the industry. He said he didn’t know Block would give such advice at the trade show; the attorney was invited, Yukelson said, because he is a “good draw and a good speaker.”

Life at The Driftwood apartments was far from perfect.

In an interview, Block said his suggestions are well within the law and help owners maximize their returns, “which is the reason why you buy income property.”

Landlords are often viewed as a monolith. But there are many different types, each with their own investment strategies.

There are professional investment firms that buy buildings in gentrifying areas so they can jack up rent.

There are big Wall Street companies that, after the financial crisis created a wave of foreclosures, bought up single-family homes and rented them out.

And there are mom-and-pop investors, who might have a day job and own a handful of buildings to pay for retirement.

Yukelson and others in the industry say many small owners provide relatively affordable housing and don’t always raise the rent. But they fear that once owners realize they won’t have an option for a big increase down the line, landlords will start to raise rent more often, maybe up to the maximum allowed.

“The decision to say, ‘I am going to forgo this money this year’ is a different decision than, ‘I am going to forgo this money forever,’” said Russell Lowery, executive director of the California Rental Housing Assn.

In interviews, some small landlords said the bill wouldn’t change anything. But at the Pasadena trade show, two owners said they plan to take Block’s advice. One said he wanted to get rid of a “problem” tenant before the new rules gave that person more power to dispute allegations.

Another, who called himself a “large mom-and-pop” with “a few hundred” units in Southern California, wanted to remove low-rent residents so he could charge higher prices.

“I have to,” he said. “I would be sabotaging myself if I didn’t and next year they put another cap on and … instead of 5%, it’s 3%.”

Asked how many people could be evicted, he said, “I don’t know — a lot.”

Neither landlord wanted to give his name.

The law was pitched not as the ultimate solution to the affordability crisis but as a way to stop the bleeding from sudden double- and triple-digit percentage increases, as well as no-fault evictions that clear entire buildings for higher-income households.

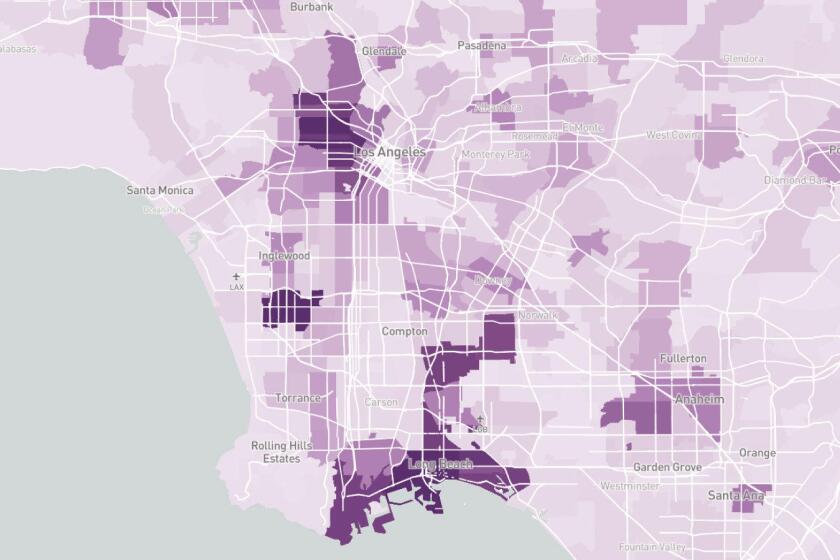

Indeed, such a cap would have staved off large hikes in some neighborhoods. In Boyle Heights, for example, median rent for non-controlled units jumped 20% in 2017 and 11% a year earlier, according to a study from the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley.

However, the analysis of 10 California communities over a five-year period found that most median annual rent increases were below 8%, which would probably be the cap in many years under the new law, given recent inflation rates.

Not everyone in the real estate industry opposed the state bill. The California Apartment Assn. remained neutral and hopes it will blunt a push for even stricter regulations. Debra Carlton, the association’s senior vice president of public affairs, said the group wanted to do “our part” to improve affordability, while limiting negative effects on property owners.

Carlton called suggestions, like Block’s, that landlords quickly remove low-rent tenants “unconscionable.” She said that needlessly spreads fear about a state law that allows a reasonable profit and is meant to stop “gouging.”

She said many property owners have been able to keep up with expenses and make a decent profit with increases below the new cap.

The bill “shouldn’t all of a sudden cause this massive change in the way you operate,” she said.

Assemblyman David Chiu (D-San Francisco), the bill’s author, said it wasn’t possible to roll back evictions that will have happened by the time the law takes effect, as the bill does with rent increases. And he said the legislation was needed because too many landlords were already removing low-income tenants to charge higher rent throughout the current real estate upswing.

“Stopping arbitrary evictions is the exact purpose of the bill,” he said. “As of Jan. 1, that practice will end.”

Property owners will still be able to evict tenants for “substantial” renovations if they pay a relocation fee equal to a month’s rent to those leaving. But the renovations can’t be cosmetic, like painting.

Miles Williams of Real Property Management Southland, which manages units in the Long Beach and Downey areas, said landlords should be able to part ways with a tenant once a lease ends. He predicted the new law will cause his company to be stricter about whom it rents to in the first place.

“Probably raise the credit score criteria, maybe raise the income criteria, dig more into the rental history,” he said.

Steve Battaglia, who owns three small properties on the Central Coast, said he’s not planning to issue quick 60-day notices before the deadline, because he’s near market rates. But he said he’ll be more aggressive with increases to maintain the value of his property. He will eventually need to refinance and one day may sell. Current rent levels will matter more during that process, he said, because banks and buyers know there are limits to increases.

“I am going to … push it as hard as I can so I am never in a position that I regret,” he said.

Last week, an upstart company started providing furnished apartments for business travelers on Franklin Avenue in Hollywood.

In Burbank, Karen Pearson called the new state bill unfair because it seems to be in opposition to the will of voters, who last year rejected Proposition 10, which would have allowed for stricter versions of rent control.

Pearson, 56, worries about her fourplex, a property she and her husband bought to get them through their eventual retirement. It’s been about three years since she raised rents. She will eventually have to replace the building’s roof and said everyday expenses such as water are likely to keep rising. One unit, a one-bedroom, is rented by an older couple who pay $400 less than the cheapest Burbank one-bedroom listed on HotPads, an apartment-hunting website.

She said removing a good tenant quickly because of the bill would be “awful,” but she feels pressure to raise rents more rapidly with caps coming.

“It doesn’t make a difference today,” she said of low rent. “But maybe it will 10 years from now.”

Larry Gross, executive director of the Coalition for Economic Survival, a tenants’ rights group, called the state bill a step in the right direction.

“I can’t tell you how many tenants said, ‘Our landlord was good but passed away, and the kids came in and jacked up the rent,’” he said.

If the experience with rent control in Los Angeles is any guide, the state bill will, in the long run, result in more stability and affordability for tenants, said Daniel Flaming, president of the Economic Roundtable.

In 2009, the research group released a study of L.A.’s Rent Stabilization Ordinance, which limits increases on buildings built before October 1978. It surveyed nearly 5,000 renters in 2007 and 2008 and found that tenants in rent-controlled units saw more frequent increases than tenants in non-controlled buildings. But when non-controlled buildings got increases, they were larger.

The cap in L.A. is more restrictive than the state cap; allowable rent increases range from 3% to 8%, depending on inflation.

The threat of displacement and loss of community takes a mental and physical toll on senior renters.

But in a separate survey for the same report, 39% of rent-controlled landlords said they didn’t usually raise rents by the maximum allowed, while 22% said it depends on the tenant. Flaming noted that factors other than the law limit a landlord’s desire or ability to raise rents. For example, property owners might not want to risk that an increase creates a costly vacancy or ruins a relationship with an existing tenant.

Overall, the Economic Roundtable survey found that tenants staying in rent-controlled units for two to 11 years wound up with a smaller cumulative rent increase than tenants staying for the same amount of time in non-controlled units. The largest savings went to those who stayed the longest.

Flaming said the state bill, with its less-restrictive cap, will provide less protection than L.A.’s law. But it will still help tenants, he said: “To have protection against very large jumps in a hot market is the major protection.”

But Lowery, of the California Rental Housing Assn., predicted the bill would make housing more expensive overall. The added costs, and time, of having to prove wrongdoing when evicting a tenant could push mom-and-pop landlords to sell to large property owners. The L.A. study found that larger landlords were more likely to raise rents up to the limit each year.

A recent study from Stanford researchers looked at rent control since 1994 in San Francisco and found that the policy kept people in their homes who otherwise would have been displaced. But caps far stricter than the state rules encouraged some landlords to turn units into condos or demolish their properties, which the researchers believed put upward pressure on rents citywide.

Landlords say that’s a reason not to impose rent control, but supporters of control see the opposite lesson. René Christian Moya, campaign director of Housing Is a Human Right, said his group backs banning the removal of rental housing from the market, as well as a 2020 ballot measure to cap rents even on vacant units.

“We have to push for more” than the state bill, he said.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.