With zero trading fees, Schwab risks blowing up brokerage model it built

Not too long ago, Charles Schwab Corp. helped to usher in the golden age of low-cost, online stock trading.

Now, the brokerage may help to kill off the fee-based business model altogether.

On Tuesday, Schwab said it will eliminate trading commissions on all U.S. stocks and exchange traded funds. The announcement — which was quickly matched by rival TD Ameritrade Holding Corp. after markets closed — sent shock waves across Wall Street. Shares of E*Trade Financial Corp. slumped 16%, while TD Ameritrade lost more than a quarter of its stock market value. Schwab’s share price also took a hit, tumbling nearly 10%.

The gambit is just the latest in an intensifying, industrywide war over fees for such things as stock trades, index funds and financial advice. And it’s squeezing not only the likes of Schwab, but also BlackRock Inc. and Fidelity Investments. These types of aggressive price cuts — admittedly a small boon for ordinary Americans routinely nickel-and-dimed by financial firms — have some observers wondering whether anyone can win in a business where more and more services are handed out for free.

For Schwab, it’s a bold, but risky move. The firm, which relies less on trading commissions than its competitors, is betting it can offset any decline of revenue by attracting more clients. It can then use their assets to generate interest income, an essential feature of its business that’s come under pressure recently as interest rates have declined.

Schwab’s online clients will qualify for zero commissions, down from $4.95 a trade, starting Monday, the firm said in a statement. It will continue to charge 65 cents a contract for options trades.

Thanks to a quirk in the legal structure used to set up the SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust, known as SPY, more than $250 billion rests on the longevity of 11 ordinary kids born between May 1990 and January 1993.

“Maybe because of the inception and growth spurt of online brokers during the dot-com boom, there’s a romanticization of the individual trader,” said Michael Wong, an analyst at Morningstar Inc. “There’s still a mindset among the investing public around the importance of commissions,” which is less important to Schwab.

Although trading costs have declined across the board, Schwab comes from a position of relative strength. The firm takes in just 7% of its net revenue from commissions. That’s far less than Interactive Brokers Group Inc. or TD Ameritrade, which both collect more than a third from trading fees.

Schwab estimated it could lose as much as $400 million in revenue a year from its zero-fee offering. Wong said that in the current rate environment, the firm would need about $20 billion or more in new deposits to offset that loss. Currently, more than half of Schwab’s net revenue comes from interest earned on its assets. The firm, which oversaw $3.72 trillion as of Aug. 31, took in almost $20 billion in net new assets that month.

Schwab last cut its trading commissions in February 2017, when it reduced them to $4.95 a trade from $6.95 to match Fidelity. Since then, assets at the firm have grown by about $800 billion from a combination of market gains and net new inflows.

Nevertheless, the company is looking for ways to reduce costs internally. Last month, Schwab said it would cut 600 jobs, or about 3% of its workforce because of the “increasingly challenging economic environment.”

Its latest move builds on an increasingly aggressive, slash-and-burn approach to price reductions. Late Tuesday, TD Ameritrade said it would match Schwab’s no-fee trading offer at a cost of as much as $240 million a quarter, or roughly 16% of its net revenue. Interactive Brokers announced just last week that it would provide free trades. And in recent months, Fidelity, Vanguard Group and JPMorgan Chase & Co. have all taken steps to eliminate fees and commissions on some offerings.

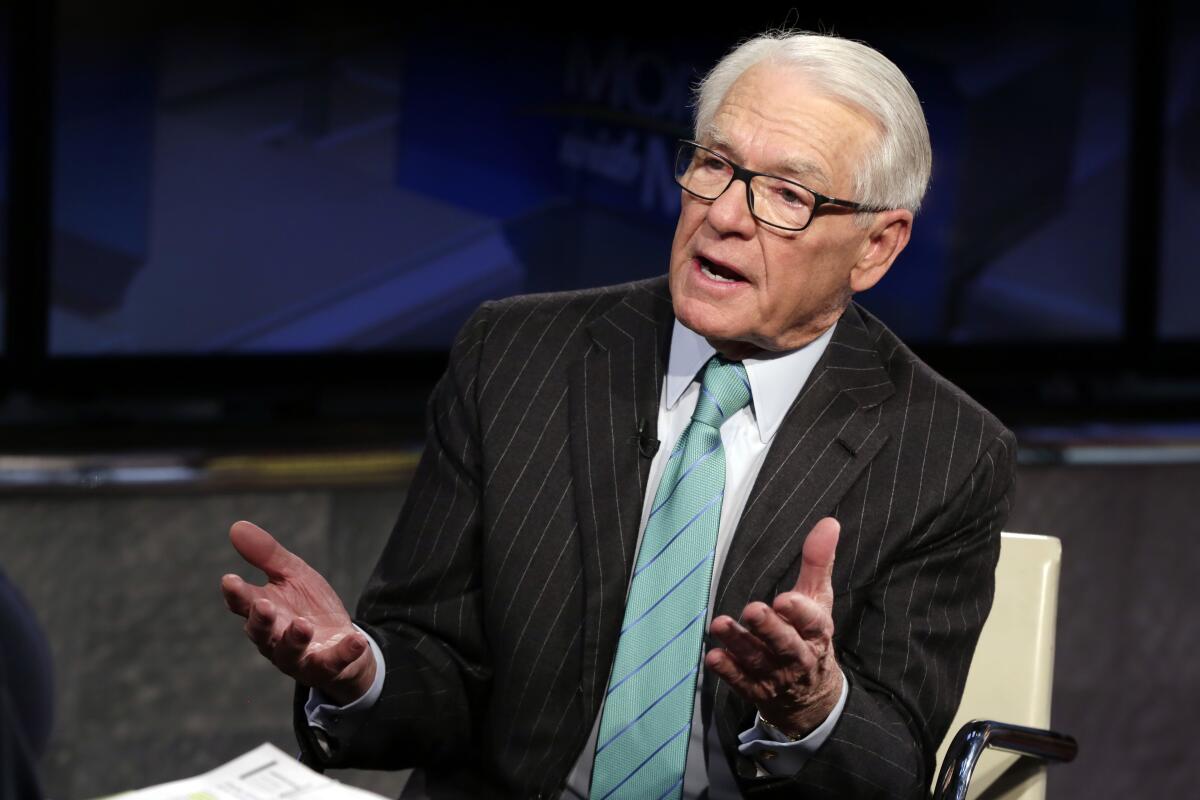

Schwab Chief Financial Officer Peter Crawford said zero commissions are an inevitable industry trend. Schwab is just trying to get ahead of that.

“We are seeing new firms trying to enter our market — using zero or low equity commissions as a lever,” Crawford wrote. “We’re not feeling competitive pressure from these firms ... yet. But we don’t want to fall into the trap that a myriad of other firms in a variety of industries have fallen into and wait too long to respond to new entrants. It has seemed inevitable that commissions would head towards zero, so why wait?”

Schwab’s billionaire founder and Chairman Charles Schwab said: “Eliminating commissions ensures my ultimate vision is realized — making investing accessible to all.”

There’s now an ETF for anyone wanting to bet on the trade war, gamble on the cannabis craze, or go all-in on the death of the mall.

The developments show just how online stock trading is becoming a commoditized business. As a result, Devin Ryan, an analyst at JMP Securities, said brokerages will need to use their platforms to generate revenue from other services. Those include securities lending, charging asset managers fees to offer their funds, and advisory services.

“They have to give a lot away for free to charge for parts of their platform that are less commoditized,” Ryan said. Firms such as TD Ameritrade might start charging subscription fees for access to data, options and margin accounts.

It’s not just brokerages that are facing pressure to cut prices. Fund managers — including BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street Corp. — have also been forced to reduce the fees they charge, particularly for index-tracking funds.

Schwab’s announcement carried echoes of the ripple effects of Fidelity’s decision to offer several free index mutual funds last year. The day Fidelity made that announcement, shares of other asset managers took a hit.

Although the splashy introduction of a free product may attract a lot of customer attention, it could also backfire, said Dan Ariely, a behavioral economics professor at Duke University.

“The odds are that what people will do is to say, ‘Schwab is offering these services for free, and so they can offer everything for free,’” he said. The risk is that “when Schwab tries to get these same consumers to do something that costs money, they may say, ‘No thanks.’”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.