Column: How the rise of streaming could turn Hollywood musicians into an endangered species

Hollywood musicians, those foot soldiers who bring the work of celebrated composers such as John Williams (“Star Wars”), James Horner (“Titanic”) and Hans Zimmer (“Dunkirk”) to life, have faced a mound of professional challenges in recent years.

Producers record their film scores in London or other overseas locations to avoid paying union scale, digital recordings have eaten away at opportunities for live players, and studios penny-pinch on music in countless ways even though their recording budgets are typically a tiny piece of a project’s budget — a $100-million project might spend less than $400,000 on musicians’ pay.

But now the musicians are facing a threat that some call potentially an “extinction-level event.” It’s the takeover of the entertainment industry by streaming video services.

Everyone now accepts that streaming breaks markets. It’s a black box that productions go into but don’t come out of.

— Marc Sazer, Recording Musicians Assn.

While the streaming boom has created a bounty for many who work in film and television by opening up a new market, and presenting a big advance in convenience for the consumer, it is a threat to musicians in three ways.

One is that they’re often paid less for a recording session for a streaming production than for feature films or studio series. Second, they don’t get residuals for productions that are made for streaming. And third, there’s almost no aftermarket for streamed productions. It’s exceedingly rare for a made-for-streaming feature or series to migrate to broadcast or cable TV or DVD, eliminating transitions from format to format that traditionally generate extra paychecks for musicians.

“Everyone now accepts that streaming breaks markets,” says Marc Sazer, president of the Recording Musicians Assn., a caucus within the American Federation of Musicians, the union representing Hollywood musicians. “It’s a black box that productions go into but don’t come out of.”

A film tax credit fiasco

AFM estimates that by cutting out residuals, streaming could eventually deprive working musicians of 50% to 75% of their income. For that reason, remaking the pay structure for direct-to-streaming productions will be a top priority of the musicians union when it reopens contract talks with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers on Oct. 7. (The alliance, the trade association that represents more than 350 producers in union negotiations, didn’t respond to my request for comment.)

To grasp what’s at stake, let’s examine how recording musicians have traditionally been paid for television and film work. The initial payment is for recording sessions themselves, which on a major feature film can run to several six-hour days at about $100 per hour. Producers pay an additional 11% into the musicians’ pension fund and a daily fee for health insurance.

Residuals sometimes account for as much as twice the initial pay, albeit doled out over time. These are paid out when a production is repurposed for a new format — a film sold for broadcast or cable showing, or converted to DVD, or sold to a streaming service such as Netflix. For some veteran musicians, residuals have been the key to a living wage.

Uber, Lyft and Doordash will spend $90 million to undercut a California employment law.

“The obvious way to make your living as you become a more seasoned musician in town is through that residual back pay,” says Blake Cooper, 35, a member of the executive board of AFM Local 47, which represents Los Angeles musicians, and a tuba player who can be heard on the soundtracks of the feature films “The Lion King” and “It Chapter Two” and the Netflix program “Umbrella Academy.”

Under the existing AFM contract, which expires Nov. 14, no residual provisions apply to direct-to-streaming productions — unlike the contracts of the screen actors, screen writers and directors guilds, which provide for back-end payments based variously on how long a production remains available on a service and the service’s subscriber tally.

Changing that structure is crucial to the musicians, many of whom assemble what Cooper calls a “patchwork” of work assignments to make a living — studio gigs and performances with freelance organizations such as the L.A. Opera and the Pasadena Symphony. “I know many musicians who are a generation or two older than myself who now get upwards of two-thirds of their annual income from residuals,” he told me.

The musicians union has been gathering statements of support from prominent composers, including Diane Warren, John Williams and Randy Newman. “Los Angeles musicians really are the best of the best,” says Justin Hurwitz, a long-term collaborator of director Damien Chazelle and an Oscar winner for his score for Chazelle’s musical “La La Land,” which he recorded with union musicians in Los Angeles. “There’s a humanity and personality they bring to score. If they’re not fairly compensated, then we won’t have that community here.”

The absence of streaming residuals in the musicians’ contract is an artifact of history. In Hollywood, streaming originally was lumped in with other “new media,” a designation applied to novel technologies that were seen as uncertain distribution formats of probably negligible importance.

Producers were unwilling to commit to residuals for these technologies, and for a time the unions went along. For the major guilds, that changed in 2007-08, around the time of a 14-week strike by the Writers Guild of America. Payment for digital distribution was a major issue in the strike, and the settlement, along with an agreement reached by the Directors Guild of America, set a new standard for new media residuals.

The musicians, however, were left behind. The AFM’s current contract still describes new media as untested and unproven technologies, even though streaming is fast becoming a dominant force. “We’re trying to catch up,” says John Acosta, president of Local 47 and a member of the AFM’s executive board.

As we’ve reported, musicians have been overlooked in film industry development initiatives in the past. California’s film incentive program hasn’t required producers to record scores in the state to receive tax credits, although a pending change in the system will give producers an advantage in bidding for the oversubscribed credits based on the wages they pay scoring musicians.

Consumers have been part of the technological sea change in entertainment distribution, perhaps without fully realizing its scale. DVDs, which only a few years ago were the principal format for on-demand home video, are disappearing. (Netflix, which originated in 1999 as a DVD-by-mail rental service and launched its streaming service in 2007, had 2.7 million DVD subscribers in the U.S. and 139.3 million streaming customers worldwide at the end of 2018.)

Union membership has been declining for decades. Can labor unions be revived? The answer is yes... if.

There’s no question that the entertainment industry sees its future in providing original programming for streaming. Industry estimates of studio spending for original streaming content run to as much as $70 billion this year, with Netflix spending as much as $14 billion, Amazon more than $8 billion, and Apple as much as $6 billion. Major studios such as Disney, NBCUniversal and WarnerMedia are rolling out their own subscription services, and Apple is preparing to jump into the pool with a service of its own.

The big push among all these entities is to create original productions for their services so that consumers will pony up subscription fees to access content they can’t get anywhere else. Walt Disney Co., which like Warner Bros. and NBCUniversal is preparing to launch its own subscription streaming service, is reportedly prepared to spend $6 billion on original content for streaming.

With deals worth hundreds of millions of dollars, the studios have lured big-name producers and television showrunners such as Shonda Rhimes, J.J. Abrams and “Games of Thrones” creators David Benioff and Dan Weiss into the streaming fold.

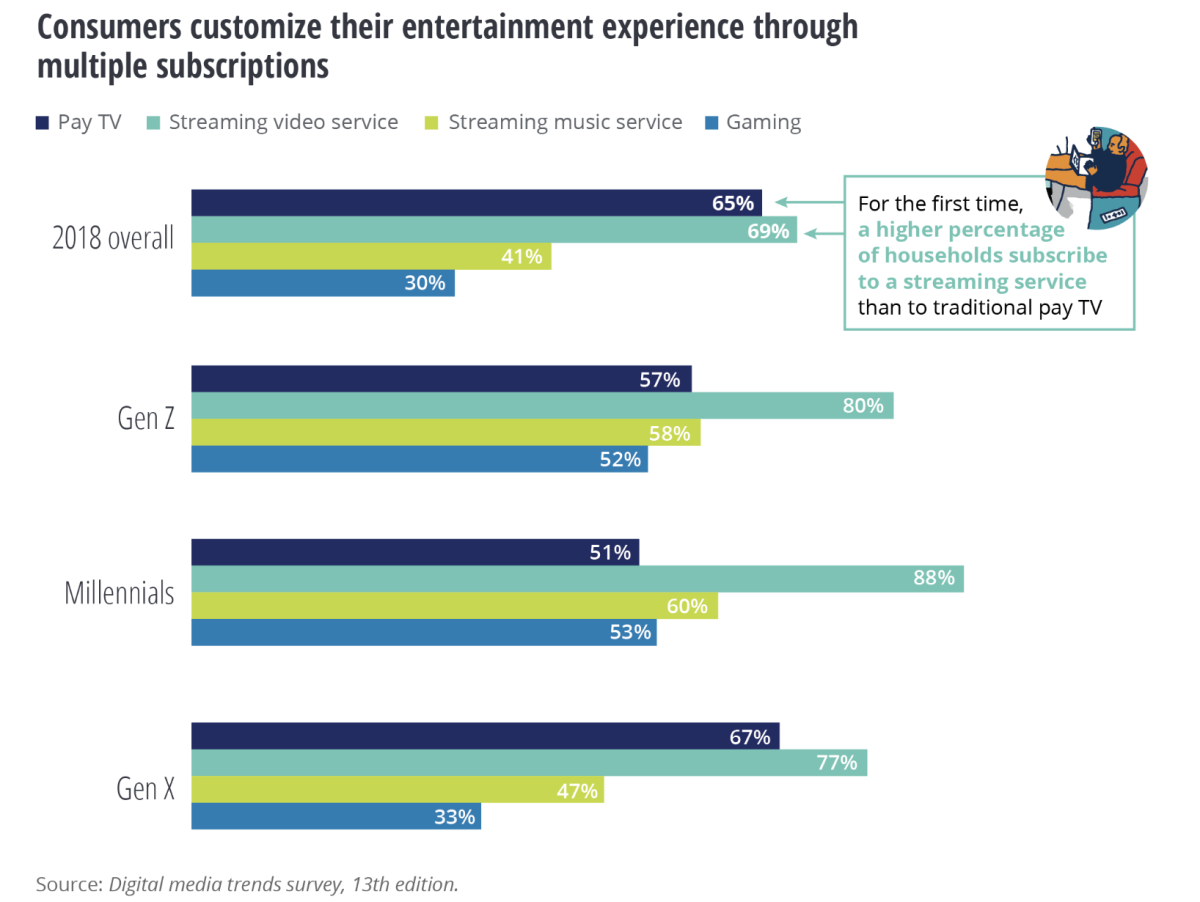

By some measures, the future is already here. Last year, according to the consulting firm Deloitte, a higher percentage of U.S. households subscribed to a streaming video service (69%) than to traditional cable or satellite pay TV (65%). The trend was driven by millennials just now moving into their high-spending years; 88% of them subscribed to a streaming service, but only 51% to pay TV. (Many, obviously, subscribe to both.)

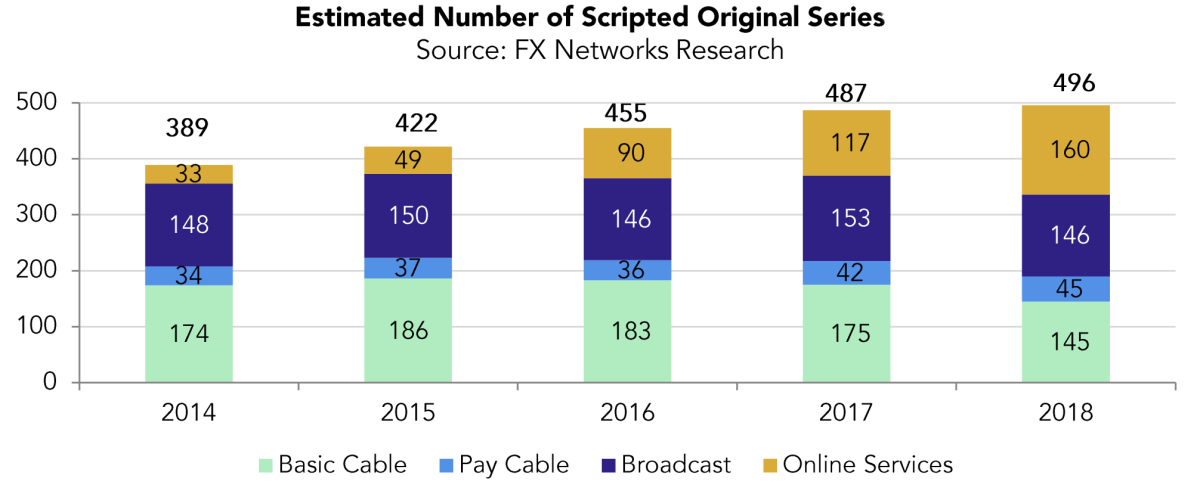

Streaming services are the only category of video that has shown growth in recent years, increasing to more than 175 million subscriptions in 2018 from about 80 million in 2014, according to the Motion Picture Assn. of America. Producers have responded by shifting their efforts to streaming services. In 2014, the MPAA reports, there were 356 scripted series on broadcast TV and basic and pay cable, and only 33 on streaming services; last year, there were 336 series on broadcast and cable, but 160 on streaming services.

Within the home entertainment market, spending on streaming has swamped DVDs and other physical video sources. In 2014, U.S. consumers spent $10.3 billion on physical video sources and $7.6 billion on digital entertainment; by last year the DVD market had shrunk to $5.8 billion and digital spending had soared to $17.5 billion.

The last round of negotiations with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, which ended in March, didn’t leave the musicians union with much optimism that producers will grant them parity on streaming residuals. “The talks weren’t very comforting,” Acosta told me.

But for the musicians themselves, the issue is fundamental. “Most of us are just trying to be middle-class workers in this economy,” Cooper says. “If the negotiations don’t go the way we hope, we’re going to be the working impoverished. We’re not going to be able to pay our bills, support a family or buy a house.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.