Column: In shocking reversal, Big Business puts the shareholder value myth in the grave

Among the developments followers of business ethics may have thought they’d never see, the end of the shareholder value myth has to rank very high.

Yet one of America’s leading business lobbying groups just buried the myth. “We share a fundamental commitment to all of our stakeholders,” reads a statement issued Monday by the Business Roundtable and signed by 181 CEOs. (Emphasis in the original.)

The statement mentions, in order, customers, employees, suppliers, communities and — dead last — shareholders. The corporate commitment to all these stakeholders may be largely rhetorical at the moment, but it’s hard to overstate what a reversal the statement represents from the business community’s preexisting viewpoint.

Stakeholders are pushing companies to wade into sensitive social and political issues — especially as they see governments failing to do so effectively.

— Investment executive Larry Fink

Since the 1970s, the prevailing ethos of corporate management has been that a company’s prime responsibility — effectively, its only responsibility — is to serve its shareholders. Benefits for those other stakeholders follow, but they’re not the prime concern. “In the Business Roundtable’s view, the paramount duty of management and of boards of directors is to the corporation’s stockholders; the interests of other stakeholders are relevant as a derivative of the duty to stockholders,” the organization declared in 1997.

The Roundtable assembled impressive firepower behind its reformulation, which bears the title, “Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation.” Among its signatories are Jamie Dimon, chairman and CEO of JP Morgan Chase and the Roundtable’s chairman; Jeff Bezos of Amazon; Tim Cook of Apple; Ginni Rometty of IBM; Mary Barra of General Motors; and the heads of major drug companies, banks, retailers, utilities and insurance companies. There’s no need to consult a who’s who to determine the royalty of American business — they’re here.

Milton Friedman should be spinning in his grave just about now.

The statement may reflect a sea change in the attitude of Big Business CEOs to challenges to their management principle coming from social organizations and especially from some candidates for the Democratic nomination for president, notably Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders. It may also represent a recognition that the federal government, once an agent of social transformation, is not currently playing that role. If issues such as income and wealth inequality, climate change and racial discrimination are going to be addressed, corporate America will have to step up to the plate.

“Stakeholders are pushing companies to wade into sensitive social and political issues — especially as they see governments failing to do so effectively,” Larry Fink, the chairman and chief executive of the investment firm BlackRock and a signer of the Roundtable letter, wrote this year in his annual letter to chief executives of the firms in which BlackRock invests.

“As divisions continue to deepen,” Fink continued, “companies must demonstrate their commitment to the countries, regions, and communities where they operate, particularly on issues central to the world’s future prosperity.”

The single most pernicious idea in modern American finance is that the corporation exists to “maximize shareholder wealth.”

Dimon, meanwhile, said in his annual letter to shareholders: “In the past, boards and advisors to boards advised company CEOs to keep their head down and stay out of the line of fire.” But “things have changed. ... If companies and CEOs do not get involved in public policy issues, making progress on all these problems may be more difficult.”

But it’s proper to approach the Roundtable statement cautiously. “We are skeptical about what the CEO signatories to this statement have in mind,” ValueEdge Advisors, a leading critic of corporate governance practices, said in its own statement Monday. “Everything will depend on how specifically and quantifiably they describe their stakeholder goals and especially how their compensation is tied to those goals. If pay is exclusively or primarily based on stock price, this statement is just an attempt at distraction. Investors should insist on more specifics and more clarity.”

The pernicious notion that a corporation exists solely to “maximize shareholder wealth” was most effectively codified by the conservative economist Milton Friedman in a 1970 essay. Friedman declared that business leaders who spoke up for the social responsibility of their corporations were “preaching pure and unadulterated socialism.”

Friedman dismissed out of hand the notion that business should “take seriously its responsibilities for providing employment, eliminating discrimination, avoiding pollution and whatever else may be the catchwords of the contemporary crop of reformers.” Chief executives who harbored such unorthodox thoughts were “unwitting puppets of the intellectual forces that have been undermining the basis of a free society these past decades,” he wrote.

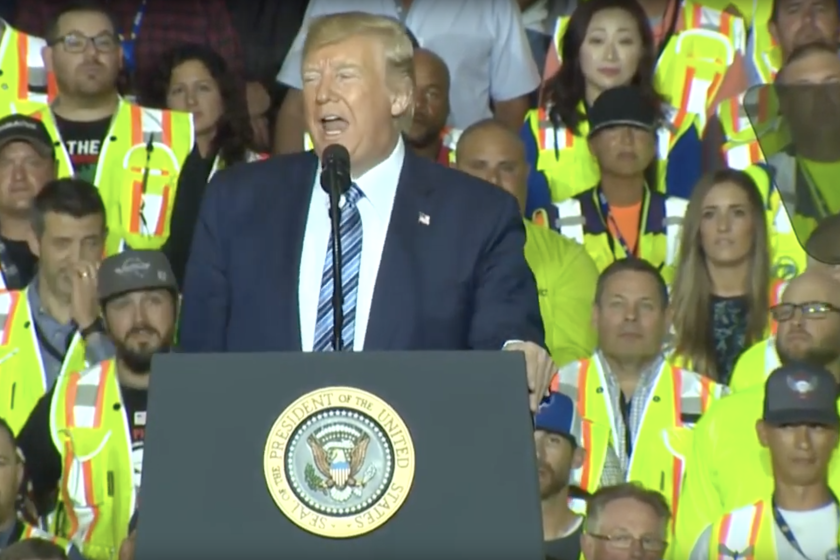

Shell Oil threatened its Pittsburgh workers with the loss of pay if they didn’t attend a Trump rally. The Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision allowed them to do it.

The idea that shareholder profits would trickle down to employees, customers and other stakeholders always was a fantasy. Maximizing shareholder wealth meant running companies with a weather eye on the stock price, maximizing dividends and buying in shares. This approach forced wages down and led to assaults on unionization, waves of layoffs, offshoring and skimpier health and retirement plans. Companies abandoned facilities in long-term host communities to reap tax abatements and other blandishments brandished by other cities. Suppliers got squeezed. Consumers seldom reaped all the benefits of these steps.

In recent years, reality has started to chip away at Friedman’s ideological absolutism. As the late Lynn Stout showed in her important 2012 study, “The Shareholder Value Myth,” Friedman proposed a very narrow definition of “shareholder interest,” interpreting it as strictly financial and assuming wrongly that all shareholders had identical interests.

Stout debunked the reliance by shareholder-value advocates on the 1919 court case Dodge vs. Ford, in which the Dodge brothers, minority shareholders in Henry Ford’s enterprise, sued for dividends and won, with the court remarking that a business enterprise was organized “primarily for the benefit of the stockholders.” As she reminded readers, this was a ruling by the Michigan Supreme Court, not a federal court, much less the Supreme Court.

Moreover, Ford then was a private company, not a public corporation with thousands of shareholders. While Dodge vs. Ford is commonly cited by ideologues, the leading state court in corporate law today, the Delaware Chancery Court, has cited the case exactly once in 30 years.

The shareholder value concept gained ground for two main reasons. First, it suggested a convenient metric for judging the performance of a corporation — its share price. The other is that it advantaged powerful economic cliques. These included the wealthy who owned corporate stocks; in 1983, the top 10% directly or indirectly owned 89.7% of all stock; in 2016, their holdings were a still-commanding 84%. They included top corporate managers, whose pay was soon pegged to share values and who were more than happy to explain that their interests and those of the corporation’s shareholders, or “owners,” were suitably aligned.

How closely the 181 corporations represented in Monday’s letter will adhere to its principles in practice remains an open question. At the very least, the signatories have signaled that they’re aware of the rumblings that the corporation’s role in American life needs to be reconsidered. But will they do more than talk?

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.