Column: Shaming Trump donors by revealing they donated to Trump? What’s wrong with that?

What’s most fascinating about the controversy raging about Rep. Joaquin Castro’s tweeting out the names of donors to President Trump’s campaign is that Castro’s Republican detractors seem to be admitting to a dirty little secret.

By complaining that he’s exposing those donors to public shaming, they’re effectively acknowledging that donating to Trump is shameful. Whoops.

To bring you up to date, Castro, the twin brother of Julian Castro, a candidate for the Democratic nomination for president, on Tuesday tweeted a list of the 44 donors in his hometown of San Antonio who have made the maximum donations to the Trump campaign this year.

Transparency...enables the electorate to make informed decisions and give proper weight to different speakers and messages.

— Justice Anthony Kennedy, Citizens United, 2010

Although Castro didn’t publicize the donors’ addresses or phone numbers, he did identify some connected to local businesses evidently of some prominence. His point was that “their contributions are fueling a campaign of hate that labels Hispanic immigrants as ‘invaders.’”

The Republican and right-wing outrage factory leaped into the fray. The National Republican Congressional Committee, a fundraising group, termed the disclosure “disgusting” and accused Castro of “inciting violence against private citizens for participating in our Democracy.”

House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Bakersfield), the mastermind of his delegation’s crushing defeat in the 2018 House elections, tweeted out a typically meatheaded complaint, labeling as “shameful and dangerous” Castro’s “targeting and harassing Americans because of their political beliefs.”

Even some journalists who should know better opined that Castro had set a “dangerous” precedent.

Is that so?

Let’s be clear about a few things. The data Castro tweeted is 100% public information. It’s all available online, right here, where it’s justifiably labeled an “open secret.” The problem with the data, if anything, is that voters don’t consult it enough.

One of the most pointless exercises beloved of our policymakers is nitpicking at a novel proposal in its earliest stages, as though the details are vastly more important than the concept.

A moment’s thought should bring home to anyone that we want and need this information to be publicly available, because shrouding political contributions in secrecy is exactly what allows big money to undermine our democracy.

Indeed, the whole point of the “scandal” ginned up by the useless former Rep. Darrell Issa (R-Vista) over IRS scrutiny of political groups masquerading as social organizations a few years ago was to discourage enforcement of the disclosure rules, the better to give cover to fat cat contributors.

Also, any reporters wringing their hands over the disclosure of campaign donors should turn in their press cards. For political and business reporters, the donor database is pure gold, mined assiduously all the time, often by the same organizations that employ the handwringers.

You may remember all the glowing predictions made for the December 2017 tax cuts by congressional Republicans and the Trump administration: Wages would soar for the rank-and-file, corporate investments would surge, and the cuts would pay for themselves.

Finally, as my colleague Michael McGough points out, the disinfectant effect of donor disclosure has been endorsed by none other than the Supreme Court. In his 2010 Citizens United opinion, Justice Anthony Kennedy tried to reassure the public that the “transparency” afforded by disclosure “enables the electorate to make informed decisions and give proper weight to different speakers and messages.”

Writing for the court majority, Kennedy acknowledged that “disclosure requirements may burden the ability to speak but “don’t prevent anyone from speaking”— and the burden is more than compensated by the gains in public knowledge.

Castro, plainly, didn’t call for or incite a violent reaction — unlike the incitement Trump engages in at his rallies and on Twitter. By identifying the businesses associated with some of the donors, he may have been calling for boycotts — but business boycott has a long and honorable tradition in America.

The harsh reality uncovered by Castro’s tweet is that politicians rely on the complexities of campaign databases to keep information about their backers hiding in plain sight. Castro didn’t merely cut and paste from the donor data, he and his staff crunched the numbers to extract the names of San Antonio residents making the largest donations to Trump. In other words, he provided his followers with a useful shortcut.

It’s true that many donors — in fact, ordinary citizens — may be unaware of and discomfited by how public their political activities happen to be. The same phenomenon happens with one’s phone number. In the old days, few people thought twice about listing their home phones; they were published in the local phone book, but accessing the white pages from afar was enough of a chore to discourage, say, stalkers.

Nowadays, however, anyone can find a listed home phone from the privacy of a computer screen located anywhere in the world. What’s changed isn’t the privacy of the number, but the concept of a private number.

The worst that can be said about Castro’s tweet is that it was mischievous. He knew his audience: members of his local community repulsed by Trump’s racism and its role in fomenting violence such as the massacre in El Paso, a mere 550 miles to the west of his hometown. His goal was to paint contributing to Trump as socially unacceptable; the feverish reaction of Republicans and conservatives suggests that he got his strategy absolutely right.

What’s most unnerving about the outcry over Castro’s disclosure is that the politicians grousing the most about it may have an ulterior motive — they want to shut down public disclosure of campaign contributions. This can only help backers of unpopular candidates and causes — wealthy donors supporting candidates who will do their bidding despite public opinion being heavily weighted to the other side.

The call by David Hogg, a survivor of the Parkland, Fla., school shooting, for a consumer boycott of Laura Ingraham’s advertisers has turned the spotlight again on the perennial questions about boycotts — Do they work?

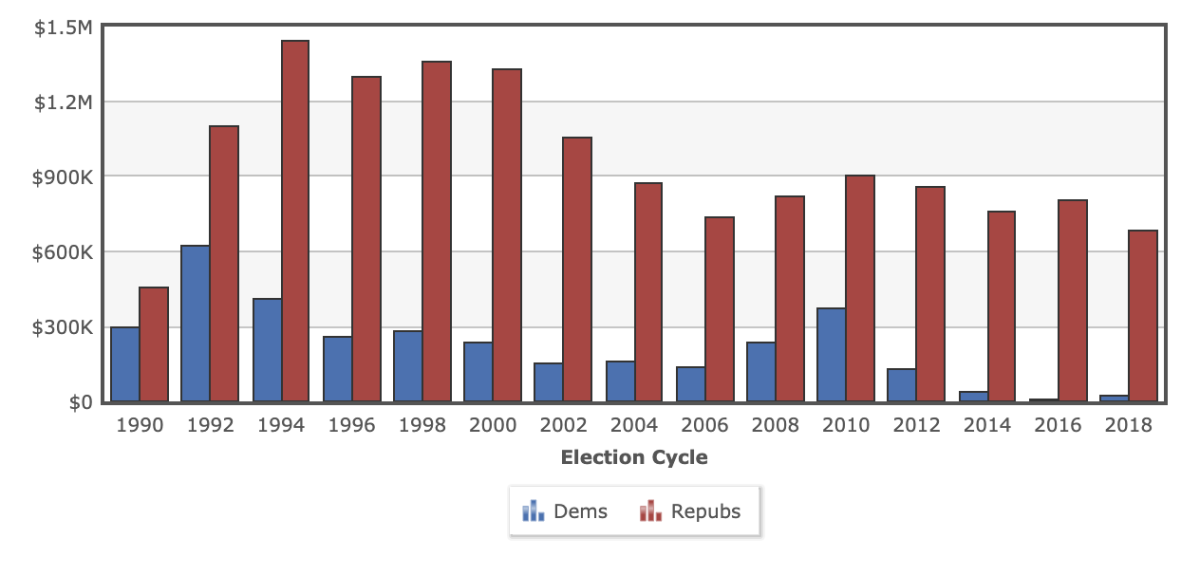

Consider the National Rifle Assn. One of the most potentially effective weapons against politicians voting against gun control measures is to expose their take from the NRA. (Open Secrets has conveniently compiled the data here.) If you’re curious why Democrats in the House are moving ahead and the Republican-controlled Senate is refusing to budge, consider that the NRA donated $19,350 to House Democrats in 2018, and $564,400 to House Republicans; among senators, $116,000 went to Republicans and $0 to Democrats. Isn’t that useful to know?

Obviously, this isn’t the first time that political contributors have been exposed to public shaming. Back in 2008, the manager of a family-owned Beverly Boulevard restaurant popular in the gay community turned up on a list of donors to Proposition 8, the Calfornia ballot initiative that banned gay marriage (until it was overturned in court). A boycott and public demonstrations ensued, and business fell off sharply. The manager eventually resigned.

That episode underscored that public shaming only works if the target has done something shameful in the eyes of his or her community. A donation to Proposition 8, which was promoted by the Mormon Church, might not have generated a boycott in Salt Lake City, but was distinctly out of place in the restaurant’s L.A. neighborhood.

By the same token, critics of Castro who have asked what the harvest would be if the names of donors to, for example, Rep. Rashida Tlaib (D-Mich.) were made public are missing the point. The disclosure might be bad for a donor located in Alabama, but the betting here is that it wouldn’t shake donors residing in her Detroit district.

Joaquin Castro plainly did a service for his constituents and for the principle of transparency in government. The only reason any people might have for claiming otherwise is that they have something to hide. Get the message?

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.