Column: Kamala Harris joins the club with a solid ‘Medicare for all’ proposal

Sen. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.), an aspirant for the presidential nomination, jumped with both feet into the healthcare reform pool Monday with a proposal to cover all Americans via an expansion of Medicare.

Harris’ plan is effectively a series of tweaks to Sen. Bernie Sanders’ “Medicare for all” proposal, which she earlier had endorsed. More on that in a moment.

The tweaks are important, in part because they may simplify the political messaging to build support for universal healthcare. And in this electoral season, political messaging is the ball game.

At the end of the 10-year transition, every American will be a part of this new Medicare system. They will get insurance either through the new public Medicare plan or a Medicare plan offered by a private insurer within that system.

— Sen. Kamala Harris

But it’s important to focus voters’ attention on the big picture. Although healthcare reform is amenable to almost infinite variation, it’s facile to describe the distinctions between Democratic or progressive reform plans as though they’re driving the party apart or are a “problem” for the Democrats.

Far more unites the Democrats running for office than divides them on this issue, and the real distinction is between the Democratic goals of expansion and inclusion and the Republican goals, which are to eviscerate coverage, leave millions of Americans at the mercy of healthcare profiteers, and destroy the Affordable Care Act without offering a responsible replacement.

These four charts trace the sudden improvement in health coverage for individuals in Obamacare

Consider a tweet issued Monday by Sen. John Cornyn of Texas, a leading member of the Senate’s GOP majority: “Again and again,” he tweeted, “Democrats have refused to join Republicans in guaranteeing coverage for pre-existing conditions.” This assertion will serve as the epitome of absurdist comedy at least until the Monty Python gang gets together again.

More to the point, healthcare legal expert Nicholas Bagley of the University of Michigan called the tweet “a profile in mendacity.” The Affordable Care Act, passed in 2010 without a single Republican vote, protects Americans from being refused or surcharged for insurance because of their medical history. Cornyn has worked hard to overturn it; among other steps, he and 35 other Republican senators signed on to an amicus brief in 2012 urging the Supreme Court to invalidate the law. (The court declined to do so.)

Democrats, on the other hand, differ chiefly in the details. Among the leading candidates, Sanders (I-Vt.) and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) have signed on to Medicare for all, Harris has done so with variations, and former Vice President Joe Biden has cast his lot with upholding the Affordable Care Act, with which he’s closely identified as a member of the Obama administration that enacted it.

Biden has taken dead aim at Medicare for all, calling it too expensive and a threat to traditional Medicare’s coverage of seniors. He proposes instead to layer a public option onto Obamacare, which would give customers an additional choice over the commercial plans that remain at the center of the ACA system.

States that failed to expand Medicaid under the ACA suffered 16,000 unnecessary deaths

Warren hasn’t put her personal stamp on a comprehensive healthcare reform proposal, beyond co-sponsoring Medicare for all. She cites, among the issues she’s running on, ensuring “real access to birth control and abortion care for all women” and “tackling the opioid crisis head on.” Here’s betting that it won’t be long before she issues her own full-throated healthcare plan.

That brings us back to Harris’ proposal. As is the case with Medicare for all, her variation would cover “all medically necessary services, including emergency room visits, doctor visits, vision, dental, hearing aids, mental health, and substance use disorder treatment, and comprehensive reproductive health care services.” Infants and the uninsured would be automatically enrolled in Medicare, though parents with employer-sponsored insurance could opt out of Medicare for their newborns. All Americans will have the right to buy into Medicare without waiting until they turn 65.

The major distinctions between Harris and Sanders involve the role of private insurers, the time frame for transition to the new system, and the source of funding.

Unlike Sanders, who would ban private insurance coverage for any services covered by Medicare for all, Harris would allow commercial companies to stay in the market, but require them to meet Medicare’s coverage and cost standards. She would allow 10 years to transition to full Medicare for all, as opposed to Sanders’ four years. And she would pay for her plan through a Wall Street transaction tax covering stock, bond and derivative trades, as well as a higher tax on offshore corporate profits. (Sanders also would increase income taxes in a way that critics say would burden middle-class taxpayers.)

Harris’ proposal has the virtue of recognizing some practical and political realities. One is that 10 years is a more plausible transition period than four years for such a radical change in the health insurance market. Extending the deadline would reduce the potential for hasty and unwise policymaking just to beat a deadline. A Wall Street transaction tax is well overdue on general principles, though whether Harris’ proposed formula would raise enough money is subject to debate.

As for the role of private insurers, it’s probably wise of Harris to acknowledge that it will be necessary to keep them in the market for some lengthy period. The insurance industry is rich and adamantly protective of its prerogatives in the U.S. economy. They’re almost certain to oppose Harris’ proposal, but their opposition will look much less defensible to the public if they’re fighting something short of total annihilation.

In this corner, Bernie Sanders, the former presidential candidate whose Medicare for All Act has become a rallying point for advocates of single-payer healthcare.

Harris’ proposal also could overcome the biggest political drawback of Sanders’ proposal, which is the prospect that all Americans with private insurance would have to give up their health plans and change to Medicare. This is the shoal on which Barack Obama’s “if you like your plan, you can keep it” promise foundered. Obama’s words were cynically exploited by ACA opponents, who somehow convinced millions of Americans that they simply adored their existing health plans.

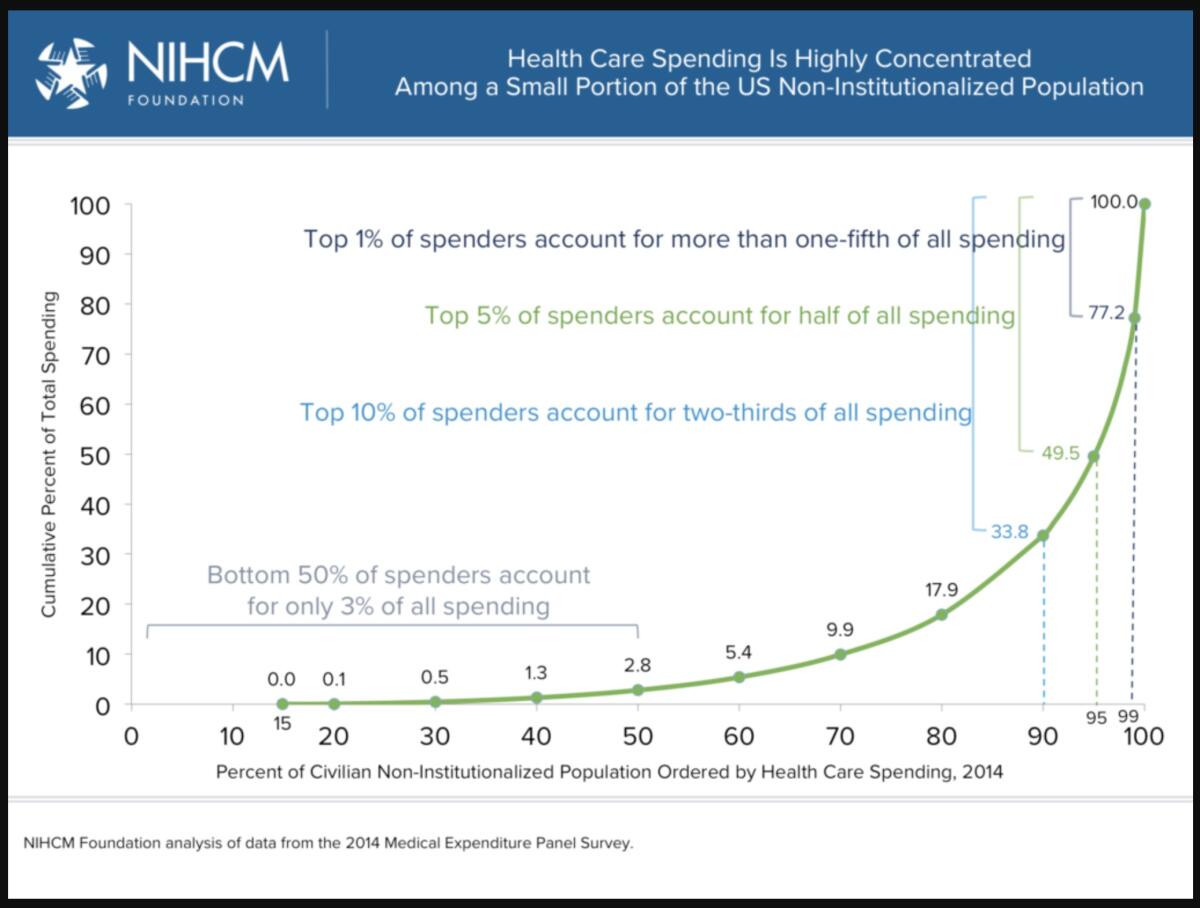

This was always misleading. Before the ACA, the newspapers were filled with almost weekly stories about patients being denied care or coverage by their health plans or being disenrolled by plans that combed through their backgrounds looking for undisclosed preexisting conditions in order to avoid playing claims. The truth is that most Americans don’t like their plans so much as tolerate them. That’s because most Americans don’t have complex interactions with the medical system or their health coverage in any given year. The bottom 50% of spenders account for only 3% of all spending and the bottom 90% account for only one-third of all spending.

The contest for worst Cabinet member of the Trump administration is what we might call “competitive.”

The question is what happens when someone does have a complex issue and a complex claim — they’re hit by a truck or get a cancer diagnosis, for instance? That’s when all the flaws of the American healthcare system appear, and that’s the target of all reform proposals such as Harris’ and Sanders’.

Since opinion polls imply that forcing people to give up their existing plans is a big negative, Harris is well advised to finesse the argument by leaving existing plans in place. “At the end of the 10-year transition, every American will be a part of this new Medicare system,” she wrote in a Medium post on the topic. “They will get insurance either through the new public Medicare plan or a Medicare plan offered by a private insurer within that system.”

The details of any reform plan offered during the campaign will be picked apart endlessly, as though every proposal is set in stone and there’s no room for compromise. That’s a misconception. Implicit in every proposal is a recognition that it’s designed to start the debate, not end it. The goal in every Democratic plan is finally to bring health coverage to every American, and that’s a claim that no Republican can make.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.