Column: Trump has turned the Department of Labor into the Department of Employer Rights

No advocates for workers’ rights or labor were especially surprised last week when President Trump nominated Eugene Scalia for secretary of Labor, succeeding the utterly discredited Alex Acosta.

Scalia — son of the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia — had made his reputation in Washington as a lawyer for big corporations resisting labor regulations, after all.

He had helped Walmart overturn a Maryland law mandating minimum contributions by big employers for workers’ healthcare, defended SeaWorld against workplace safety charges after a park trainer was killed by an Orca (he lost that case), and had written extensively against a federal regulation expanding ergonomic safety requirements.

Trump is pursuing the most hostile anti-labor agenda of any modern president.

— Pedro da Costa, Economic Policy Institute

But Scalia’s appointment is best seen not in the context of his own legal career, but in the context of Trump’s assault on worker rights and welfare. Despite his positioning himself during his presidential campaign as a flag carrier for the working class, Trump has rolled back numerous pro-worker regulations from the Obama era and before.

He talked a good game about bringing back manufacturing and coal jobs, but that hasn’t materialized. His steel tariffs are credited with saving some 12,000 steel manufacturing jobs, but at the enormous cost to the economy of an estimated $900,000 per job.

Alexander Acosta may bear the title of U.S.

That’s paid by steel users, including automakers and other manufacturers. General Motors says it took a $1-billion hit in 2018 from the tariffs. That contributed to its decision to shed 14,000 jobs globally and to shutter its assembly plant in Lordstown, Ohio, costing 900 jobs. Although Trump attacked GM Chief Executive Mary Barra for the decision, he also turned his ire on UAW and AFL-CIO leaders, calling them “not honest people” and blaming high union dues for the Lordstown closing. (Union dues are paid by workers, not employers.)

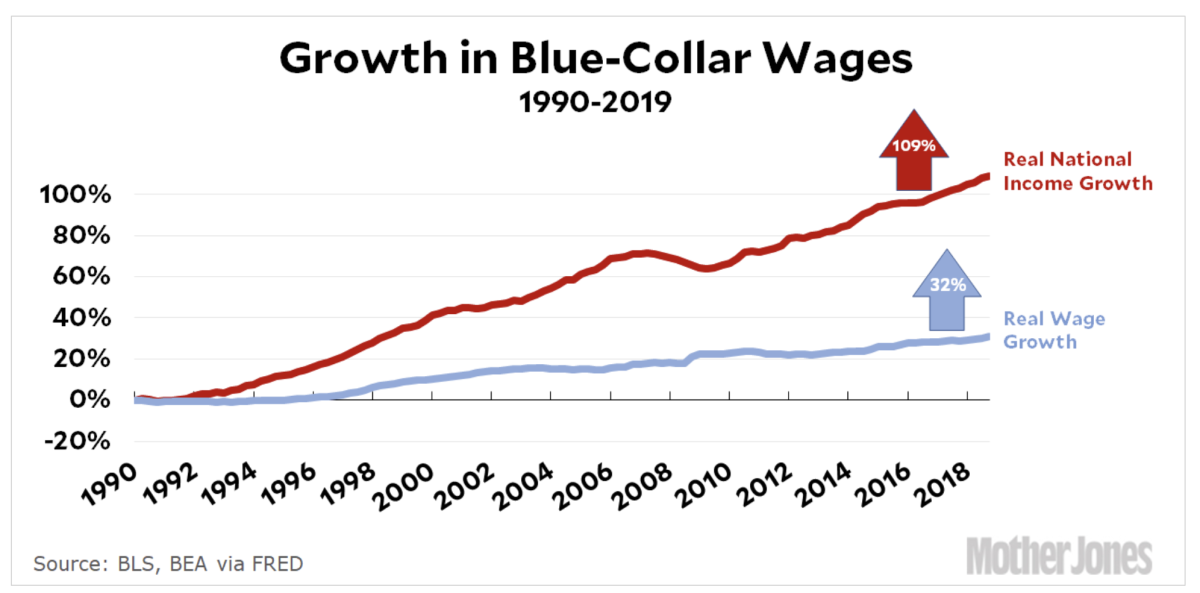

Hourly wages for rank-and-file workers are up since Trump’s inauguration, but only at a measly rate after inflation. Wages rose about 3.1% in June over a year earlier, but with consumer inflation running at 1.6% during the same period, the real gain for workers was a mere 1.1% in a year. Workers’ share of economic growth remains dismally low and continues to fall under Trump.

The real hubs of Trump’s attack on workers are the Department of Labor and the National Labor Relations Board. These bodies were established to protect worker rights. As we’ve reported before, under Trump they’ve become the advance guard in eviscerating those rights. Through those agencies, writes Pedro Nicolaci Da Costa of the labor-oriented Economic Policy Institute, “Trump is pursuing the most hostile anti-labor agenda of any modern president.”

Under Acosta, the Department of Labor rolled back a rule proposed by the Obama administration expanding overtime pay to thousands of workers misleadingly designated as “supervisors.” The Obama rule would have raised the pay threshold under which workers would be guaranteed overtime pay to $47,476 from $26,660, where it had settled for more than a decade. Trump’s labor regulators propose fixing it at $35,000, reducing the number of covered workers in half, leaving behind about 6 million workers who would have been covered under the Obama proposal.

As Terri Gerstein, a labor expert at Harvard Law School, observed in March, the Trump proposal would work out to less than $17 an hour — not exactly what most would consider “supervisor” pay — and would be silent on fast-food chains’ habit of suspiciously loading up their restaurant workforces with “general managers, assistant managers, night managers, managers for opening and closing and delivery, all paid a weekly salary.”

Trump’s NLRB has reversed the board’s trend toward expanding the definition of “joint employer,” which would have made big franchisers such as McDonald’s jointly liable with their franchisees for violations of employees’ wage and hour rights. Its proposed definition would narrow the joint-employer standard “to the point at which many workers would find it nearly impossible to bring all firms with the power to influence their wages and working conditions to the bargaining table,” according to the labor-oriented Economic Policy Institute.

The Congressional Budget Office, that nonpartisan arbiter of the impacts of federal legislation, reports that raising the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour would increase the wages of 27 million Americans and lift 1.3 million out of poverty as of 2025.

The Trump administration also has rescinded the Obama-era “persuader” rule, which required employers to disclose their relationships with union-busting law firms. The Labor Department has indicated it will take a hands-off approach to enforcing workplace regulations when employees have agreed to bring workplace disputes to arbitration. That drew an objection from Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), who observed that affected workers often have been “forced to sign away important legal rights” and therefore are “most in need of federal protection.”

That brings us back to Eugene Scalia, who would be almost certain to continue Acosta’s policies, which included fighting legislation to raise the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour from its woefully outdated $7.25. Scalia’s career has demonstrated his affinity with employers and bankers; back in 2012, the Wall Street Journal labeled him one of the financial industry’s “go-to guys for challenging financial regulations.”

His 2000 campaign against the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s effort to impose more responsibility on employers for ergonomic-related worker injuries such as carpal tunnel syndrome gives a good taste of his approach. In an essay for the Cato Institute he lamented that the rule would “require businesses to slow the pace of production, hire more workers, increase rest periods and redesign workstations or even entire operations.” He asserted that OSHA’s intention to expand the rule to home-based work for employers reflected Democrats’ intention to “court union leaders” ahead of the coming presidential election.

The Trump administration is full to the brim of pro-employer front persons. The last place another one is needed is the Department of Labor. Scalia’s appointment to that agency, which is expected to be waved through by the Republican-controlled Senate, will merely continue a void in worker rights in Washington.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.