Property owners aim to tap into an urban-foodie vibe

Traditional Southern California supermarkets, already facing growing competition from leviathan discounters such as Wal-Mart and Target, are now catching blows on another flank as markets catering to environmentally conscious foodies proffer local fare in laid-back settings.

Souped-up gourmet stores like Whole Foods Market long ago claimed a big share of the grocery business. But today it is smaller neighborhood stores, which aspire to offer customers top-drawer local fare, that are crowding in on the action.

Real estate experts see it starting to happen in a variety of neighborhoods across the Southland. As one of these hip markets opens its doors in downtown Los Angeles, an indoor farmers market is in planning stages at an apartment complex nearby. And in Santa Barbara, a developer is replacing a Vons supermarket with condominiums above a collection of mini stores selling local artisanal foods.

Shifts in the way people seek out and buy their food are changing the way that landlords use their real estate.

With big-box stores including electronics purveyors, home furnishings stores and many supermarkets on the outs with consumers, developers are incorporating food outlets in other settings, including residential complexes and former industrial buildings. It’s a rethinking of commercial properties: Warehouses become stores, supermarkets are recast as a collection of specialty stores and condo complexes make room for merchant-tenants.

“As people become more health-conscious, we are seeing a greater number of organic grocers permeate the market,” said real estate broker Richard Rizka of CBRE Group Inc. The overall amount of space devoted to traditional supermarkets in the U.S. is declining as competitors large and small offer competing visions of grocery shopping, he said.

The new Urban Radish market in downtown L.A. reflects the socially conscious views of its Arts District patrons, co-owner Carolyn Paxton said. The former metal warehouse, bedecked with a mural of giant chipmunks, is stocked with fare tailored to the palates of urban foodies.

The produce is selected from small farms. The beef — even in the hot dogs — was grass-fed and never saw a feed lot, she said. There is locally produced small-batch ketchup for sale, and even the mustard, mayo and aioli sauce used to make sandwiches is whipped up on the premises.

“The food that we have here has been curated,” Paxton said. “Every item has been tasted and tested, and it’s amazing.”

On the edge of the market’s parking lot are a dozen electric-vehicle charging stations that serve residents of nearby former industrial buildings that have been converted to condominiums. Arts District locals tend to be “liberal, socially conscious artists and entrepreneurs,” Paxton said, and Urban Radish reflects their predilections.

Santa Barbara: Public Market

Santa Barbara real estate developer Marge Cafarelli, meanwhile, is aiming to reflect tastes in the prosperous coastal community with a setting that is upscale but not pretentious.

Her goal is to create a multi-merchant market that offers exquisite-tasting food at prices competitive with Whole Foods. Her Santa Barbara Public Market will also sell some everyday necessities such as kitchen accessories and eco-friendly cleansers.

“I want a full grocery experience for Mrs. Jones,” said Cafarelli, evoking expectations for her typical customer.

Cafarelli’s model will differ from traditional food stores’ in that it will operate more like the Ferry Building Marketplace in San Francisco or Pike Place Market in Seattle, where multiple merchants ply their wares under one roof.

Both Urban Radish’s owners and Cafarelli are taking pains to bring in goods at a variety of prices and hope to avoid being perceived as elitist. They also strive to please customers who have sophisticated, even lofty, expectations.

“Santa Barbarans are well traveled and have seen more places than I have been,” said local olive oil expert Jim Kirkley, who will operate an outpost of his Il Fustino oil store when the Santa Barbara Public Market opens in September.

Kirkley buys oil made by local olive growers and expresses casual disdain for the bland imported green stuff typically found in stores and restaurants.

“Olive oil should have a peppery kick,” he said. “You want a little peppery tickle in your throat and it should have some pungence — that’s the antioxidants.”

Such erudite advice about a cooking staple was no doubt rarely voiced in the Vons supermarket that once occupied Cafarelli’s State Street site, and therein lies a challenge for the developer and her band of artisan entrepreneurs.

“Vons used to be the neighborhood market,” said chef Kristen Desmond, owner of Flagstone Pantry. “It’s important this isn’t the other end. It should be a market for everybody.”

Santa Barbara may indeed be the kind of town where Desmond, a former IBM management consultant, can succeed at her true passion without being branded elitist — making tasty dairy-free, egg-free and gluten-free baked goods. She already sells her food at a popular local coffeehouse, which gave her credibility with Cafarelli.

“These businesses are proven, beloved concepts in Santa Barbara,” Cafarelli said of her planned market tenants. “Santa Barbara has accepted them.”

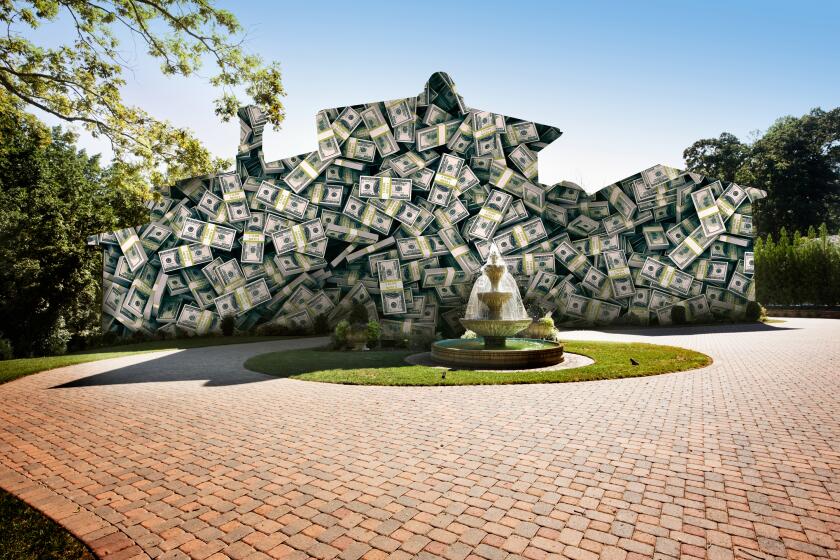

City officials wanted more than another supermarket on the prime downtown real estate once occupied by Vons and a parking lot, Cafarelli said. She is incorporating her market into a $50-million Alma del Pueblo mixed-use complex that will also house 37 condos. It is being built in the Spanish Colonial revival style required in the city’s historic core.

“I want it simple but elegant,” she said, “to look like it’s been here 100 years.”

Downtown: Medallion

Back in downtown L.A., a much newer-looking market is taking shape in one of the city’s oldest neighborhoods — within one of its newest apartment complexes.

Landlord Saeed Farkhondehpour is counting on downtown’s residential comeback and growing demand for fresh, farm-to-table food to recast retail space that never took off.

Farkhondehpour completed his Medallion apartment and retail complex at Main and 4th streets in 2010. He expected that the numerous small retail spaces he built would be rented by wholesalers who would sell a variety of products to retailers. For years, nearby blocks were full of such enterprises selling apparel, sunglasses, toys and other goods.

“That market never really recovered” from the recession, Farkhondehpour said. Downtown apartment rentals and restaurants did recover, however, and the developer pivoted to catch the new wave.

He has joined forces with John Edwards, whose Calabasas company, Raw Inspiration, runs 23 farmers markets with thousands of vendors. Their bold plan: to turn the Medallion complex into what Edwards calls “foodie heaven.”

The Medallion’s small, vacant shops will be offered to artisanal food sellers, Farkhondehpour said, and a larger space conceived as a grocery store will become a farmers market operating from four to seven days a week.

Other spaces are being turned into proper restaurants, including the first permanent location for popular caterer Bigmista’s Barbecue.

Edwards and Farkhondehpour hope to have their operation up and running by Jan. 1, although some of the Medallion’s restaurants are already open.

The pair hope that the Medallion, with its built-in parking structure and central location, will become a regional draw for people who might otherwise be patronizing traditional grocery stores.

“The timing is right. The location is right,” Edwards said. “It certainly does worry supermarkets.”

Twitter: @rogervincent

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.