The trigonometry of terror: why the Las Vegas shooting was so deadly

Arthur B. Alphin is well acquainted with the trigonometry of terror.

The retired U.S. Army Lt. Colonel and West Point graduate, who has a mechanical engineering degree and specialized in ballistics, has testified in many multiple shooting cases.

What he sees so far about the Las Vegas shooter Stephen Paddock is a patient, well-trained gunner who did not pick and choose his targets, but held to a steady kill zone centered in the middle of a thousands of concertgoers.

Once the trigger was pulled, simple laws of physics and trigonometry sealed the fate of more than 500 people who would fall wounded in the ensuing fracas — 59 of them fatally.

“He had a huge area of three, four or five football fields with people standing shoulder to shoulder,” said Alphin. “He was not aiming at any individual person. He was just throwing bullets in a huge ‘beaten zone.’”

Beaten zone is an infantry term dating to World War I. Shaped like the area a searchlight casts across a flat surface, it represents the area where bullets can strike, and moves substantially with tiny changes in the tilt of the gun.

If the shooter shifted by roughly one degree, or the width of two fingers held at arm’s length, Alphin said, the beaten zone would fall outside the crowd.

“That’s all the distance you have to move and you aren’t hitting anybody,” Alphin said. “So he had to be pointing or aiming at the very center of mass and then bouncing all over with the recoil.”

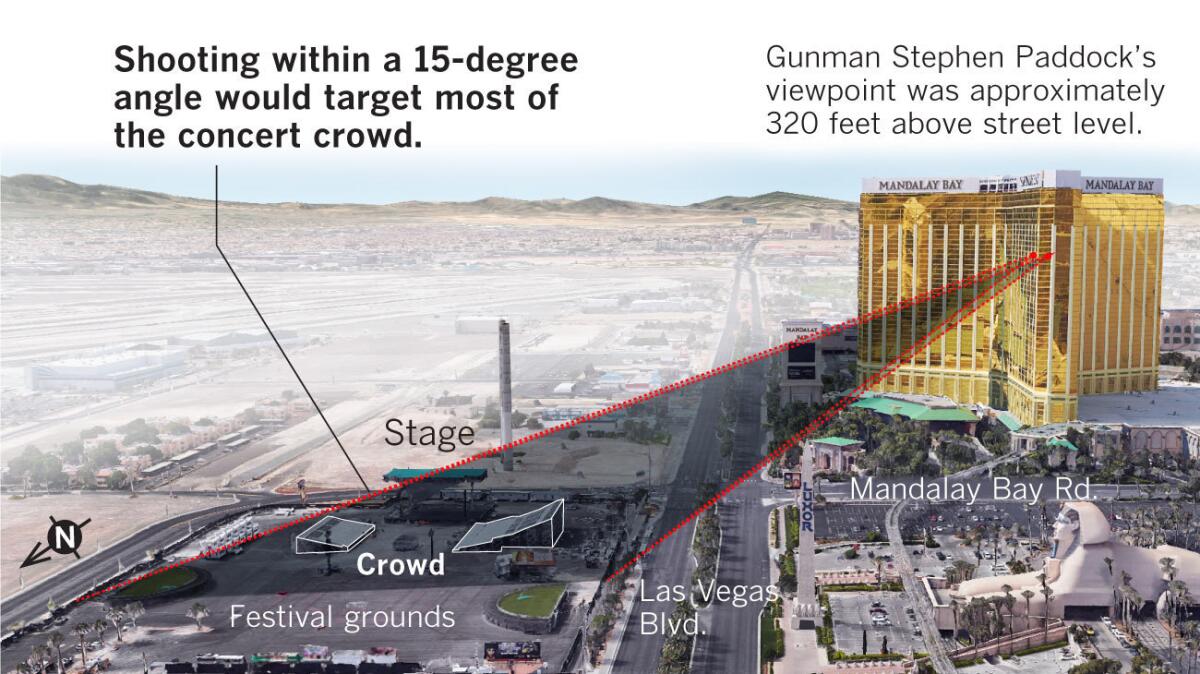

From a perch 320 feet above ground in a hotel whose base was about 1,050 feet from the concert venue, Paddock was firing down the 1,098-foot hypotenuse of a right triangle — and would have to adjust his aim for the arc of the bullet over that distance.

Alphin said there was “no way” the shooter maintained such a steady kill zone by dumb luck. Steady nerves and planning are a better explanation for the casualty rate, he said.

“How did this guy get trained that well? Where did it come from?”

At least one of the 23 rapid-firing weapons authorities found in the hotel room had a bipod stand to hold it steady, according to law enforcement authorities.

Paddock also may have fitted weapons with a device to make it cycle rounds more quickly into the chamber for firing, or converted some to fully automatic firing, potentially adding as many as eight rounds per second, Alphinsaid.

There may also be expertise at work in deciding when to switch rifles, Alphin said. Gun barrels expand as they heat up, and the bullet can lose contact with the grooves that spin it and keep it point-forward. Without the spin, it will tumble.

“A bullet tumbling like that, Good God, it will land on planet Earth but you don’t know where,” Alphin said.

Follow me: @LATgeoffmohan

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.