Obama saw low-wage workers as struggling moms. Trump may see them as suburban teens

Reporting from Washington — Andy Puzder, the fast-food executive who is President Trump’s nominee for Labor secretary, fondly recalls his first job: scooping ice cream at Baskin-Robbins for a buck an hour as a teenager near Cleveland.

“I learned a lot about inventory and customer service,” the chief executive of CKE Restaurants Inc. told The Times last year. “But there’s no way in the world that scooping ice cream is worth $15 an hour, and no one ever intended it would ever be something that a person could support a family on.”

Those comments encapsulate the starkly different approach the Trump administration is expected to take on low-wage workers and their issues compared with the Obama administration.

To President Trump and other Republicans, fast-food jobs and other low-paying work are largely for young people just getting started in the labor market. An increase in the federal minimum wage to $15 from the current $7.25 would reduce those opportunities, hurting workers and businesses, Republicans say.

That view is part of a broader Trump goal of slashing 75% of federal regulations and reducing regulatory oversight to try to stimulate economic growth and job creation.

Republicans and many business owners have criticized former President Obama’s efforts to expand access to overtime pay. They complained that the Labor Department has been overly aggressive in seeking back pay from employers accused of wage theft, as well as in issuing guidance limiting the ability of companies to classify workers as independent contractors and making companies take more responsibility for actions by franchise owners.

Obama and his fellow Democrats viewed federal workplace regulation as a force to push back against the sliding fortunes of lower-rung employees. The share of overall U.S. income going to workers, rather than capital, has fallen steadily since 2001, for instance.

One manifestation of that trend, they argue, is that many low-wage workers these days are trying to support a family — and those workers need a higher minimum wage and strong federal policies to make ends meet.

“This notion that the minimum wage doesn’t need to be raised because all it is is pocket change for teenagers so they can go out and buy sneakers isn’t reflective of today’s labor market,” said Tom Perez, who was Labor secretary under Obama from 2013 until stepping down last month.

“These are breadwinners for families in many, many cases,” he said.

Both sides can point to data to support their positions.

Republicans note that the Labor Department reports minimum wage workers tend to be young. In 2015, the most recent data available, workers under 25 years old made up only about one-fifth of hourly paid workers. But they were 45% of workers earning the federal minimum wage or less. (Some workers, such as students and those earning tips, are exempt from the minimum wage.)

Overall, there were about 2.6 million workers earning at or below the minimum wage in 2015, about 3.3% of hourly paid workers, according to Labor Department statistics.

“If the minimum wage were raised, these individuals would have a harder time finding jobs,” said Diana Furchtgott-Roth, a former Labor Department chief economist during the George W. Bush administration.

“There will be more encroachment of technology into the low-wage jobs that have served as entry points for teens and low-skilled workers,” said Furchtgott-Roth, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, a free-market think tank. “If you have $15 instead of $7.25 [minimum wage], then these low-skilled workers just aren’t going to get hired.”

A 2014 report by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office found there were pluses and minuses of hiking the minimum wage. The report determined that an increase to $10.10 an hour would cause the loss of about 500,000 jobs nationwide. But the increase also would boost the earnings for about 16.5 million low-wage workers.

Workers-rights advocates said the Labor Department statistics are misleading because they exclude many people who earn just above the minimum wage.

The UC Berkeley Labor Center said a better definition of low-wage workers is those earning less than two-thirds of the median hourly wage. In California, that meant earning less than $13.63 an hour in 2014, the most recent year analyzed.

About a third of workers in the state — roughly 4.8 million — earned less than that amount, the Labor Center said. The average age of those workers was 35.

The share of low-wage workers who were teens declined to 5% in 2014 from 16% in 1979; the share of low-wage workers ages 35 to 64 increased to 44% from 32%.

Working at Carl’s Jr. — one of the chains owned by Puzder’s CKE Restaurants — isn’t a starter job for Nancy Hernandez, 34. She has put in seven years at the company, working at different locations across San Jose. She’s now a supervisor and makes $13 an hour. Hernandez’s husband makes less than she does working at a Vietnamese restaurant.

“We are living on this work,” Hernandez said. “I have to pay rent” — $1,700 for a one-bedroom apartment — “and pay bills and buy what the kids need.” There are five, ages 1 to 16.

Some younger people at the restaurant move on to jobs that pay more, she acknowledges. But when presented with the argument that the minimum wage shouldn’t go up because fast-food restaurants aren’t meant for long-term employment, Hernandez gets defensive.

“They are rich,” she says of business owners generally. “They don’t know anything about our lives, how we suffer to make the effort to make ends meet and live.”

These are workers living paycheck to paycheck, and if they get cheated out of wages and overtime, they can’t feed their families.

— Tom Perez, former Labor secretary

The Obama administration unsuccessfully pushed for an increase in the federal minimum wage to $12 an hour and embraced the “Fight for $15” movement. That effort, led by fast-food workers, unions and liberal activists, has produced state and local minimum wage hikes in California, New York and elsewhere.

Under Obama, the Labor Department’s Wage and Hour Division forced employers to pay more back wages to their employees than under the Republican administration of former President George W. Bush.

In the first seven years of the Obama administration, through 2015, the division recovered $1.59 billion in back wages compared with $1.46 billion for all eight years of the Bush administration.

Perez said the Obama administration targeted low-wage sectors, such as fast food, because their workers were the most vulnerable. The garment industry, which has a major presence in Los Angeles, was another focus. Under Obama, the Wage and Hour Division conducted more than 1,000 investigations in Southern California alone, leading to workers getting more than $11.7 million in back wages.

Trump has sent mixed messages on a federal minimum wage increase but has been clear he doesn’t support anything close to $15.

Puzder also has indicated he’s open to a small minimum wage increase.

“Instead of creating a living wage, the fight for dramatic minimum wage increases could leave millions with no wage at all,” Puzder wrote in a Wall Street Journal column in 2015.

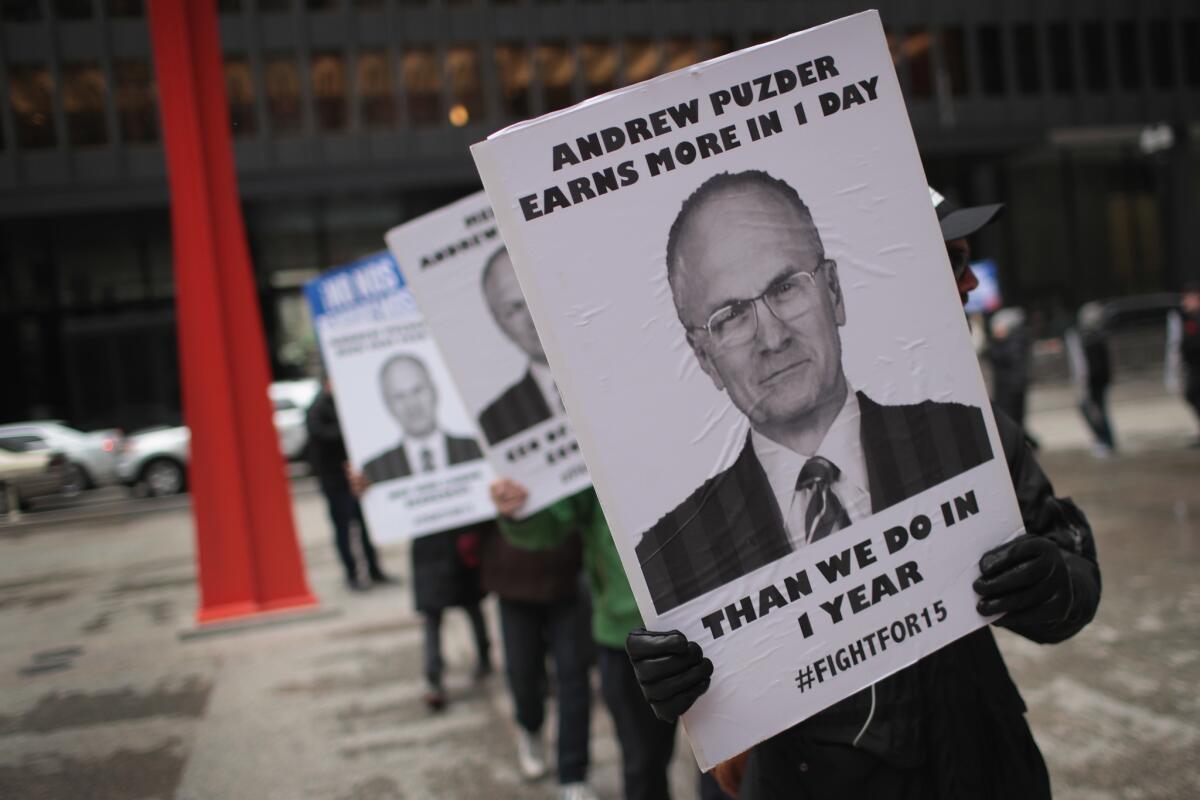

Trump’s decision to nominate Puzder, whose Carpinteria-based company includes the Hardee’s fast-food chain as well as Carl’s Jr., outraged Democrats and worker-rights advocates.

Puzder has criticized new federal rules expanding overtime pay, which have been blocked by a federal judge. He also has infuriated worker-rights advocates by talking about the advantages of increased automation in the fast-food industry.

His nomination has triggered protests and an aggressive campaign to try to derail his confirmation. Puzder’s Senate hearing has been delayed four times as he works to divest his business interests to avoid conflicts of interest.

“This isn’t a man who has the needs of workers first and foremost in his mind, and that’s what the Labor secretary should be,” said Judy Conti, federal advocacy coordinator at the National Employment Law Project, which advocates for workers rights.

An analysis in September by Bloomberg BNA found that about 60% of Labor Department investigations of Carl’s Jr. and Hardee’s restaurants since 2009 resulted in at least one violation of the Fair Labor Standards Act, which covers minimum wage, overtime and other regulations.

But as Puzder and his supporters point out, that was one of the best performances by leading fast-food outlets.

In nominating Puzder, Trump said the fast-food executive would “fight to make American workers safer and more prosperous by enforcing fair occupational safety standards and ensuring workers receive the benefits they deserve. And he will save small businesses from the crushing burdens of unnecessary regulations that are stunting job growth and suppressing wages.”

Even some business owners who aren’t enthusiastic about all of Puzder’s qualifications believe having a restaurant executive at Labor could be good.

“Having someone who understands what it’s like to run a business and the challenges of today’s economy, hopefully that’s helpful,” said Michaela Mendelsohn, who owns six El Pollo Loco restaurants in Los Angeles and Ventura counties.

She has doubts about Puzder’s lack of government experience. And Mendelsohn, who is transgender, says she’s particularly concerned about complaints lodged recently by employees of CKE Restaurants that they were discriminated against or sexually harassed. Still, she said, “There is something to be said for the difficulties of the regulations.”

But Democrats and workers’ advocates fear that Trump’s Labor Department will reduce enforcement efforts designed to protect low-wage workers.

There was some criticism of the Labor Department’s more aggressive actions. One labor attorney who represented employers told a 2011 House hearing that the Wage and Hour Division had developed a “gotcha” approach that was “increasingly punitive.”

But Perez, who is running for chairman of the Democratic National Committee, said the Obama administration was trying to protect Americans struggling to survive in low-paying jobs.

“These are workers living paycheck to paycheck, and if they get cheated out of wages and overtime, they can’t feed their families because they have no margin for error,” he said.

Perez sees that approach changing under Trump.

“I don’t have a lot of optimism about the ability of low-wage workers who are victimized by systematic violations to have a receptive voice in this administration,” Perez said.

Follow @JimPuzzanghera on Twitter

Times staff writer Natalie Kitroeff contributed to this report.

ALSO

People from all around California are heading to the Central Valley to defend Obamacare. Here’s why

Trump and Congress may make it easier to get drugs approved — even if they don’t work

U.S. utilities seek solar power as Trump sides with coal, fossil fuels

Travel executives worry about Trump’s effect on their industry

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.