Why Trump’s obsession with trade deficits is misguided

Throughout his young presidency, just as he did in the campaign,

If only the United States sold more to the rest of the world than it bought overseas, Trump argues, the country would take a dramatic turn for the better. That would be true especially in manufacturing, the thinking goes, where the shift to foreign factories has cost millions of American jobs.

But focusing so much on the trade deficit as a scorecard on economic health, many experts say, is not only misguided, but it also diverts attention and resources away from problems that will have a far bigger impact on Americans’ long-term well-being.

No question U.S. trade in goods is lopsided

But while Trump’s fixation on trade deficits has proven to be an effective political message, he overstates their economic importance, critics say.

The flaw in using deficits or surpluses to size up U.S. commercial relations with any single country, which Trump tends to do, ignores the complexities of trade in today’s global economy.

The trade gap with Mexico, for example, looks very big — $63 billion last year. But the reality is that about 40% of the value of the goods imported from Mexico is made in the U.S.

Trump vs. economists

Experts say trade deficits:

- reflect a low savings rate relative to consumption and investment

- don’t necessarily give the U.S. an advantage at the negotiating table

- if reversed, may not add many new jobs due to automation

The problem is aggravated by the president’s informal, zig-zag approach to trade policy. Last week, Trump suggested he was about to tear up the 23-year-old North American Free Trade Act. Hours later the White House said amicable negotiations over modifying the deal are on track.

Similarly, Trump’s fondness for off-the-cuff remarks, which he sometimes acknowledges later were based on insufficient understanding of the issue, make it hard for administration officials to focus on basic strategies.

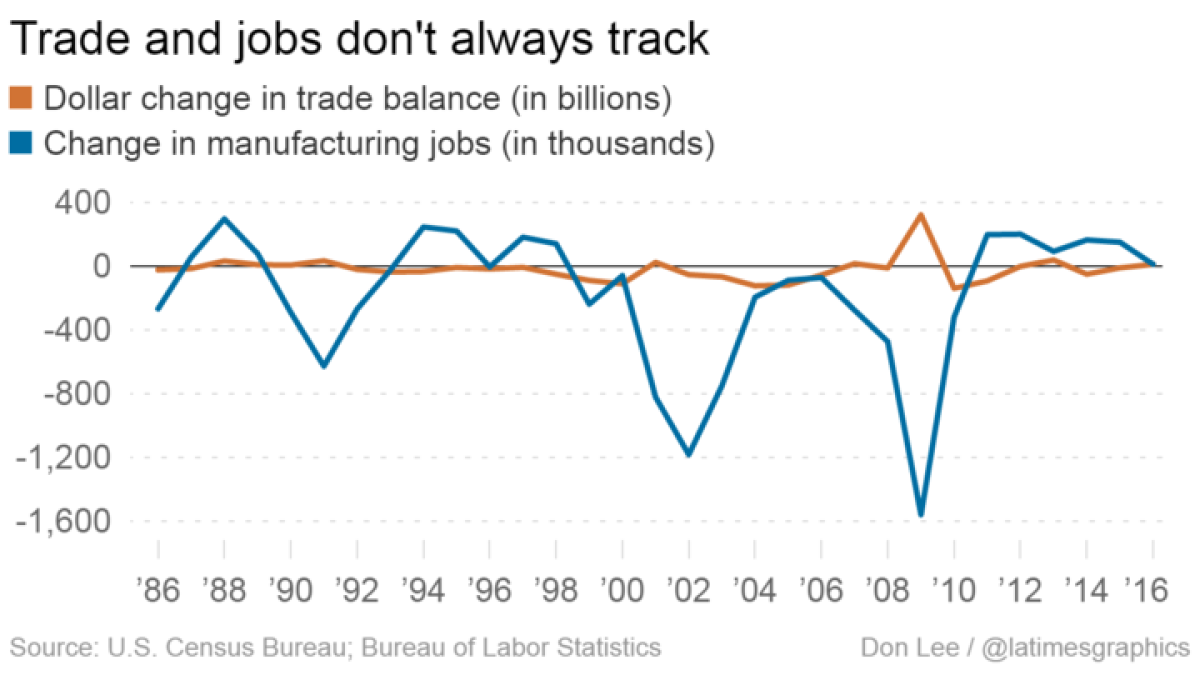

The link between trade deficits and jobs is not so clear

Changes in the trade balance and the number of manufacturing jobs have often moved in opposite directions. During economic downturns, U.S. trade balances tend to improve amid sharp drops in imports even as factories cut back on employment.

Trump may be overplaying his hand when it comes to the impact of deficits. He thinks big trade deficits give the U.S. leverage to make trading partners offer sweeter terms.

“We have massive trade deficits. So when we’re the country with the deficits, we have no fear,” he said last week when asked whether he worried about sparking a trade war after slapping tariffs on Canadian lumber.

But having a big deficit doesn’t give the U.S. a particular advantage at the bargaining table, said Wendy Cutler, a top trade negotiator in the Obama administration.

Even the opposite may be true, some say: Big deficits can reduce U.S. bargaining power because any sudden action to cut back imports would send damaging shock waves through the nation’s economy.

Trump’s tax plan may undermine his trade goals

Because Trump’s tax proposal does not have enough spending offsets to pay for the cuts, it will increase the national debt.

That higher borrowing by the U.S. government will push up interest rates.

Higher rates will attract global investments in U.S. Treasury bonds.

Increased demand for U.S. bonds will tend to strengthen the U.S. dollar.

The rise in the dollar means American exports will become more expensive and imports will be cheaper.

Weaker demand for U.S. exports and cheaper prices for imported goods will worsen the trade deficit.

Focusing on deficits overlooks more important factors

While no one argues that trade deficits are a good thing, most economists see them as symptoms of deeper problems. Addressing those long-term problems is likely to yield better results than haggling over present-day trade deals, which harm some Americans but help others.

High on the list of long-range changes needed to assure future prosperity for the United States is increasing the skills of American workers. To borrow a term from the world of sports, it’s a matter of “matchups.”

Today, many American workers compete head-to-head with foreign workers for jobs that require relatively modest skills and education. That’s a matchup U.S. workers cannot win, because workers in most other countries are paid less and what they produce can be sold for less.

The answer, economists and other analysts say, is to train Americans for positions that require more technical skills than the low-wage foreign workers possess.

Investing in more education and training will pay especially big dividends because the increasingly high-tech economy of the future will make lower-skilled workers less and less valuable.

That will take time and money. But so far, such investment does not seem to be a priority for Trump.

“We have to focus on upgrading skills of American workers,” said Raghuram Rajan, a University of Chicago Booth School of Business professor and former governor of India’s central bank. A lot of the new jobs, he added, are in the service industry, but getting them into rural areas and smaller communities is a big challenge. “These are important questions that the administration has to ask.”

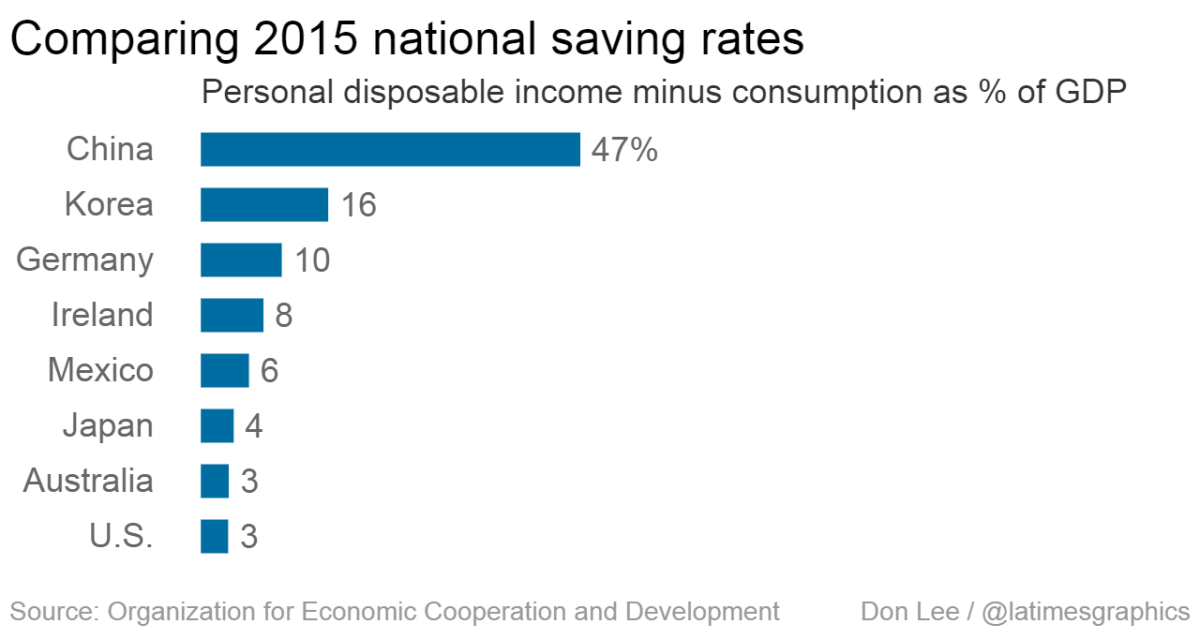

The dismal U.S. saving rate is a bigger factor

Another long-term problem that is largely going unaddressed is the admittedly arcane issue of how much money Americans — and the federal government — save. For many years, Americans have saved at much lower rates than the countries that have risen to become major economic challengers, especially China.

Why does saving matter so much? After all, by becoming a nation of consumers, not savers, most Americans enjoy one of the highest standards of living in the world.

The trouble is that because the country is saving too little, it is indirectly paying for much of its consumption — and its investments — by borrowing from foreigners. Trump’s tax plan unveiled last week would only make matters worse, policy experts say, because his proposal for massive tax cuts for businesses would increase U.S. government debts by trillions of dollars, which would tend to push up the trade deficit.

In one sense, the most important U.S. export is the dollar. Because the dollar is considered the safest currency in the world, foreign nations and wealthy firms and individuals buy and hold huge reserves of greenbacks, even though they earn very little interest.

That may help U.S. consumers and the government in the short run, but the failure of Americans to save more means the country has trouble financing the big modernization and educational projects that would give it a better future.

“The intuition is that if you make U.S. firms and workers more productive, they’ll be more competitive internationally. And if they’re more competitive, we’ll be able to export more,” said Barry Eichengreen, professor of economics and political science at UC Berkeley who was a senior advisor to the

“But if you haven’t done anything in the meantime to change savings or investment, you’ll also be importing more — and you will not have narrowed the external deficit.”

What worries Eichengreen is that Trump may, in fact, end up discouraging savings with his deregulation of financial insitutions and other policies. Trump administration officials, he said, “are not exactly informed by economic literacy.”

To be sure, most economists and trade specialists applaud efforts by Washington to make its trading partners play fairly, which many don’t always do. U.S. exporters face a range of barriers that countries erect against imported goods, barriers that are not immediately recognizable as trade policies.

Trump recently ordered a probe of exporters of cheap steel, a move aimed at targeting China’s huge overproduction of steel that has caused a global glut and slump in prices. That has made American-produced steel hard to compete, even though just 3% of U.S. iron and steel imports last year came from China.

“Our government has done nothing to stop the trade cheating that is rampant in the world,” said Dan DiMicco, former chairman of steelmaker Nucor Corp. and a principal trade advisor to Trump during the campaign.

In some cases foreign governments will impose highly demanding health and safety rules for imports, even though they may be more interested in discouraging imports than in protecting their citizens. But most trade specialists say that attacking these and other barriers require careful and time-consuming efforts by U.S. officials, not dramatic unilateral action.

If Trump remains focused on his fiery rhetoric about trade deals such as the

For instance, hundreds of thousands of cars assembled by U.S. automakers in Mexico and then imported into the American market contain parts or major components made in this country. So, quick action to curtail auto imports would have quick negative effects on many U.S. factories and workers.

It would take many years and billions of dollars to build new assembly plants inside the United States. Moreover, highly automated new plants would need only a fraction of the workers employed in the old auto industry.

Worse, the expected jobs might never return to U.S. shores at all. They could likely just shift to other lower-wage countries.

That’s what happened a few years ago when Washington levied big tariffs on imported Chinese tires. China accounts for nearly half of the United States’ $735-billion deficit in tradable goods and Chinese tires were seen as a particularly sore point.

The tariffs did make Chinese tires more expensive. But, instead of resulting in a surge of demand for American-made tires, U.S. purchasers shifted to Thailand, Indonesia and other low-cost producers, with little change in domestic industry employment.

The tire story is not unique. Experience shows that attacking a trade gap with one country by applying tariffs or other restrictions often increases the deficit with another country that is making and shipping those same products.

“What Trump is trying to suggest is that if we impose some kind of import barrier, we’re going to get a bunch of jobs back,” said Edward Leamer, director of the UCLA Anderson Forecast. “And that seems highly doubtful.”

Follow me at @dleelatimes

ALSO

Trump's 'big beautiful wall' is not in the spending plan. Will it ever get built?

Trump's frustration with budget compromise has him considering merits of a 'shutdown'

Congress on track to deliver sweeping spending bill, but not much else

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.