Patrick Soon-Shiong — immigrant, doctor, billionaire, and soon, newspaper owner — starts a new era at the L.A. Times

A 43-year-old woman lay dying on the floor of the emergency room lobby at Martin Luther King Jr.-Harbor Hospital as her boyfriend frantically called 911 for help from a pay phone outside.

Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong read about it in the Los Angeles Times.

“That story,” he recalled recently, “it haunted me.”

Soon after the 2007 article was published, the billionaire physician drove across town to visit the troubled hospital south of Watts. He tracked down the doctor who was in charge that night and told him, “This is completely unacceptable.”

Soon-Shiong went on to provide a crucial financial guarantee to assist Los Angeles County’s efforts to build the modern Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital. The story also helped Soon-Shiong recognize the importance of journalism to his life — and to the life of the community.

“I wouldn’t have known had it not been in the paper,” he said during a recent interview.

Now, Soon-Shiong finds himself on the cusp of taking ownership of The Times. It will be his highest-profile venture in a long and lucrative career that began halfway around the world in South Africa.

His planned $500-million purchase, announced Feb. 7 and expected to close this month, will return the 136-year-old newspaper to local ownership after 18 tumultuous years under Chicago control.

The deal includes the San Diego Union-Tribune, Spanish-language Hoy and several small Southern California community papers, including the Glendale News-Press and the Daily Pilot in Costa Mesa.

On Friday, as he addressed The Times’ staff for the first time, Soon-Shiong announced the newspaper would leave its historic Art Deco building in downtown L.A. — its home since 1935 — when the lease expires June 30, and move to El Segundo, just south of Los Angeles International Airport.

Patrick Soon-Shiong plans to move Los Angeles Times to new campus in El Segundo »

Soon-Shiong’s purchase comes at a perilous time for the publishing industry as advertisers migrate their dollars to Facebook and Google, and as readers have become less willing to pay for print subscriptions.

Newspapers across the country have been reeling from the shift by slashing their newsroom staff. In less than three years, The Times’ parent, Tronc, has shed about 1,400 employees, with most of those coming from operations outside its newsrooms. That represents nearly a fifth of the company’s workforce.

The newsroom in January overwhelmingly voted to join a union to try to preserve jobs. Plans were in the works to cut up to 20% of The Times’ staff and close its Washington, D.C., bureau, Soon-Shiong said, news that spurred him to act “as desperately fast as possible” to save the paper.

“The idea of reducing the newsroom and getting rid of the Washington bureau — I thought if we didn’t move, that would be the death knell of the institution as we knew it,” he said.

Soon-Shiong’s purchase appeared to halt such massive cuts.

I thought if we didn’t move, that would be the death knell of the institution as we knew it.”

— Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong

Soon-Shiong said he intends to invest in and bring stability to a newsroom that has been led by three editors in nine months and five publishers in four years. He is vowing to return the storied paper to prominence after more than a decade of corporate changes, seesawing strategies and buyouts and layoffs, which have left remaining journalists anxious and demoralized.

“Task One for me: to ensure that we have a newsroom that stands up to the likes of the Washington Post and New York Times,” Soon-Shiong said. “We need to strengthen our voice again.”

Soon-Shiong, 65, has lived in Los Angeles for 38 years and is one of its richest residents, with a fortune estimated at $7.6 billion by Forbes. He holds a small ownership stake in the Lakers, runs a cluster of healthcare companies, operates a cutting-edge biotech laboratory in Culver City and, last year, rescued six small California hospitals. He has pioneered medical treatments and performed scientific experiments for NASA’s Space Shuttle program. Last year he twice visited Donald Trump just before the president’s inauguration (Soon-Shiong said he is politically independent).

As impressive as Soon-Shiong's business profile is, he is untested in the field of journalism. And he has remained an enigma in a city full of flashier and more recognizable billionaires.

Like many Angelenos, Soon-Shiong’s story starts far from the diverse and boundless city that he would one day call home.

He was born and grew up in the coastal city of Port Elizabeth in South Africa. His parents arrived from China after the Japanese invasion during World War II.

Soon-Shiong was the fifth of eight children. His parents owned a general store, surrounded by a lead-acid battery factory, a tire manufacturer and a meatpacking plant. His father also served as village doctor and neighborhood herbalist, routinely receiving metal cans full of plant snips shipped from his homeland.

“If anybody had a fever, a cough or a boil, there would be a knock on the door, they'd walk into the house and he would concoct something,” Soon-Shiong recalled in a 2016 interview with the National Museum of American History. “I’d sit there and watch.”

This was during apartheid, and South Africa’s institutionalized racism permeated everyday life. For a young Soon-Shiong, it meant at times feeling like an outsider. “We were not black, and we definitely were not white,” Soon-Shiong told the museum. “We could get on the bus, but we couldn’t sit in the regular compartments with everyone else.”

One of his classmates, Judy Forlee, who still lives in Port Elizabeth, remembers attending the segregated school with Soon-Shiong because they were “not allowed to go to the white schools.”

“He was a very bright boy,” Forlee said. “He was top of the class and was quite outspoken in class.”

As a teenager, Soon-Shiong delivered the Port Elizabeth Evening Post to earn money for college, an experience he relished.

“To this day, I hear the ‘clackity-clack’ sounds of those metal printing presses,” Soon-Shiong wrote last month in a letter to Times employees. “I still smell the oils of the machines and see the ink smeared on the pressmen’s uniforms.... I vividly recall the excitement of being among the first to read the headline of the day, hot off the presses.”

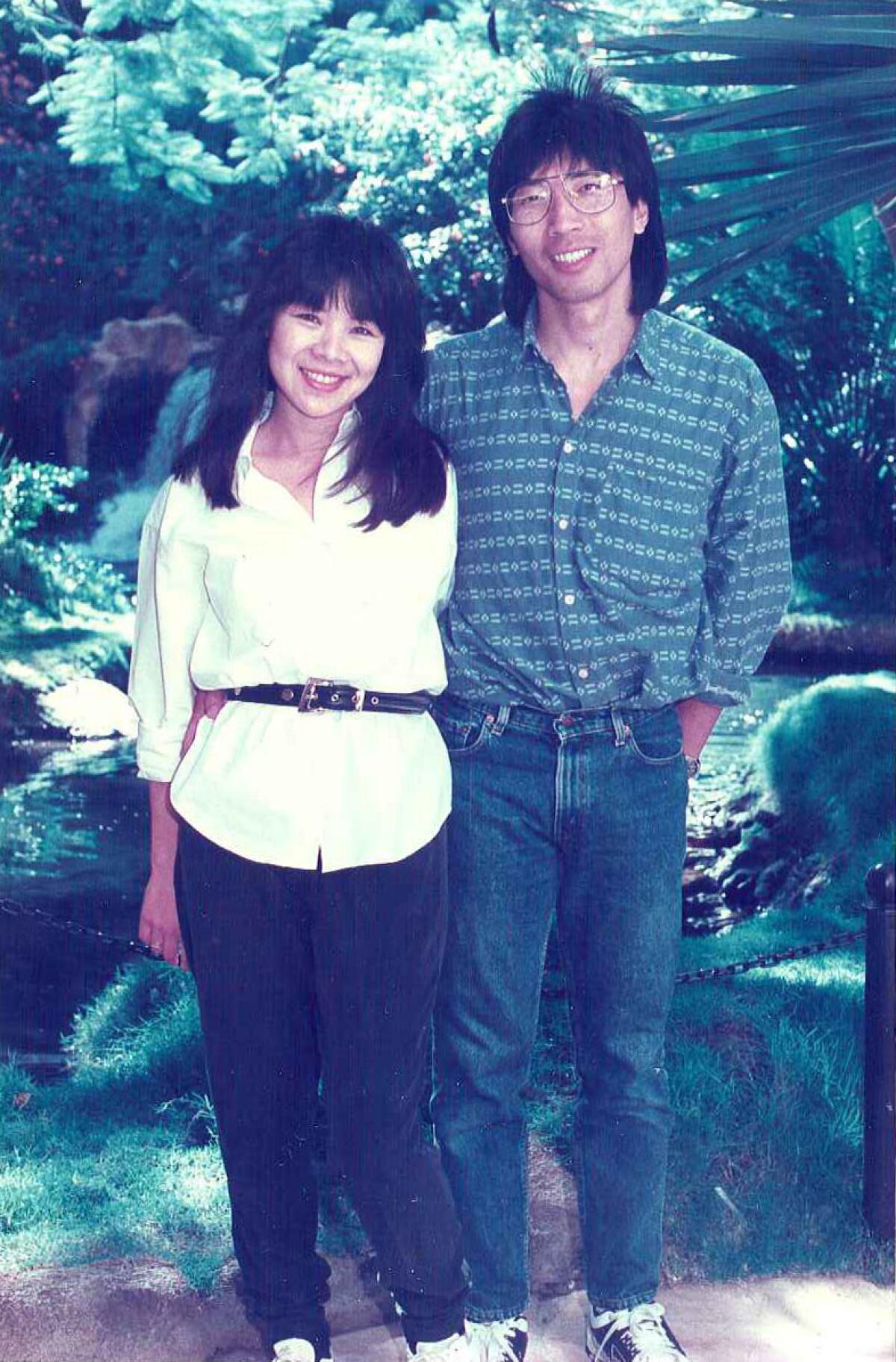

His calling, though, was medicine. Exceptionally driven, he excelled academically and entered college at 16. During his second year of medical school, he met his future wife, Michele B. Chan, who also grew up in South Africa. They met at a basketball game — his other love.

He graduated near the top of his class with a medical degree from the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg in 1975 when he was 23.

After college, Soon-Shiong needed special permission to work at Johannesburg General Hospital, which was then reserved for whites. He was determined to be accepted, and would become one of the first nonwhite physicians to practice at the hospital. He was eager for the opportunity to work with the best physicians, he said, even if it meant earning only half the salary of a white doctor.

The Soweto uprising in 1976 came a year into his residency. He was an intern at the large Baragwanath Hospital in the township, where he volunteered to treat black students injured in the clashes. He said he was struck by the dignity of those who had been beaten by police. Later, he cared for children with tuberculosis. Those experiences made an indelible impression that continues to shape his views.

“We always were the underdogs — that’s the best way to describe it,” he said. “So I have great empathy for people who are underdogs, for whatever circumstance they’ve been put in: whether poverty, whether religion, whether race, color, creed.”

He and Michele moved to Canada in 1977, the year they married, and he worked as a surgical resident at Vancouver’s main hospital and also earned a master’s degree. His mentor relocated to Los Angeles, and in 1980, Soon-Shiong followed him.

“We took literally 100% of our belongings into a single U-Haul,” he said. “I drove nonstop. I arrived here and I hit this thing called the 405, and I’d never seen six-lane freeways in my life.”

The sprawl of Los Angeles was jolting. Michele was horrified by the cost of rental apartments near UCLA — about $400 a month. She burst into tears, worried that they would not be able to afford it. The couple had no car, just a hand-me-down TV that required an occasional slap on the side to get it to work.

Soon-Shiong got a job at the Veterans Administration, then joined the UCLA faculty in 1983 when he was 31. Meanwhile, Michele became a television actress, appearing in the ABC drama “Hotel,” and later as Dr. Donna Chen in “Danger Bay,” a 1980s family adventure series that ran on CBS. She also appeared on “MacGyver.”

Los Angeles — with its fusion of cultures — began to feel like home.

Soon-Shiong’s career was taking off, too. The young surgeon first appeared in The Times in 1986 after he performed the first pancreas transplant on the West Coast. He left UCLA five years later to develop drugs — first for diabetes, then to treat cancer.

On a recent Monday morning, Soon-Shiong warmly greeted reporters visiting NantWorks, the Culver City umbrella company for his various ventures that he founded in 2011. Slender and fit, the physician was impeccably dressed in a dark business suit, crisp white shirt and blue tie dotted with tiny puppies. His wife picks out his ties, he said.

Those who have worked with him say he’s brilliant — but demanding. He thinks ambitiously, striving to figure out how pieces fit together to create the big picture.

“He can be impatient — he sees a problem and he wants to solve it,” said political researcher and pollster Frank Luntz, who recalled meeting Soon-Shiong about four years ago at an NBA dinner in Indianapolis. “I didn’t know who he was and he wanted to talk about cancer, and I just wanted to talk about basketball.”

Whether the lessons he learned as a doctor, researcher and entrepreneur can be applied to owning a media company in troubled times remains to be seen, although he has demonstrated patience in allowing companies to develop against the odds.

He amassed his fortune by building, and then selling, two drug companies. In 2008, he sold injectable-drug maker American Pharmaceutical Partners to the German company Fresenius for $4.6 billion. Fresenius was looking to expand its business in the U.S., and APP’s sales of injectable generic drugs to hospitals and clinics were growing. The company provided such common treatments as heparin, hormones, progesterone, vitamin supplements and diuretics.

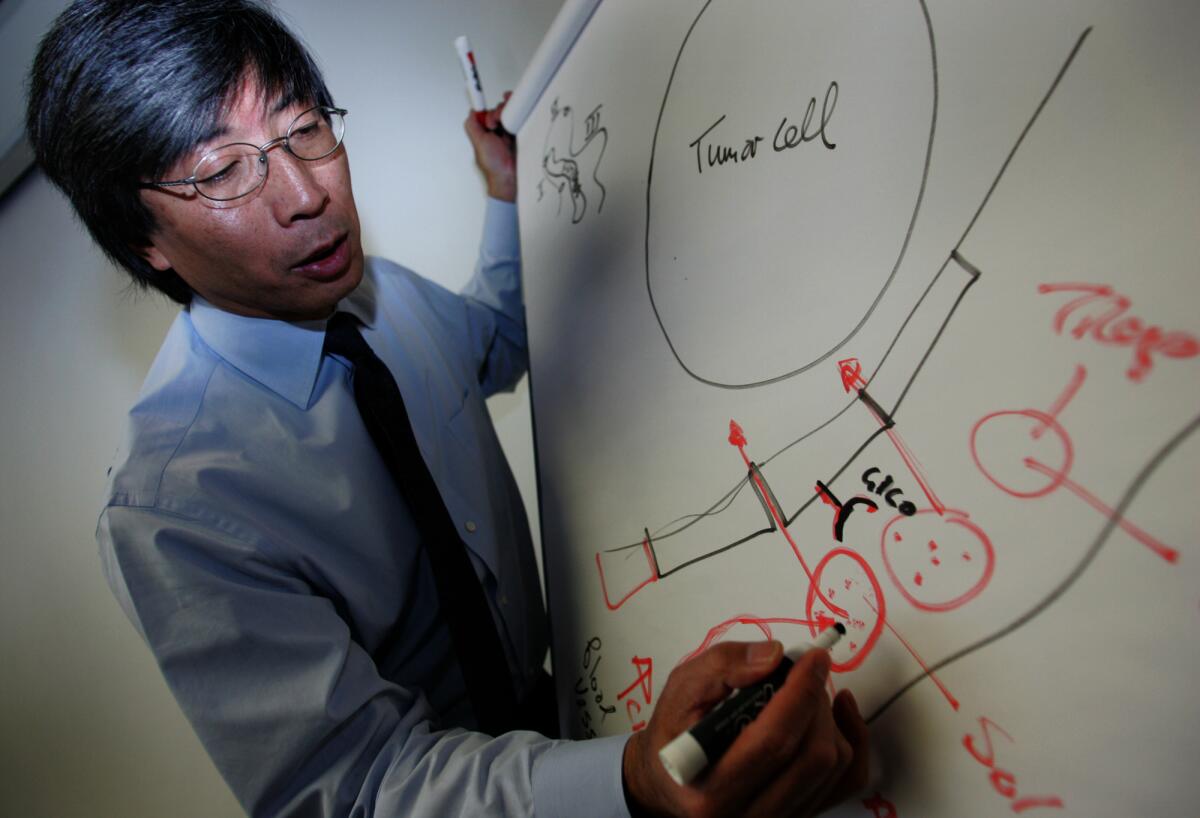

Soon-Shiong also worked more than a decade developing the drug Abraxane, which showed promise in the treatment of advanced pancreas, breast and lung cancers without some of the side effects of other drugs. The Food and Drug Administration approved the drug’s use in 2005, and five years later he sold the company behind it, Abraxis BioScience, to biopharmaceutical giant Celgene for nearly $3.8 billion. Abraxane continues to do well in the market; its sales last year reached nearly $1 billion, according to Celgene.

With his success has come controversies and legal feuds.

One of the most contentious disputes came 20 years ago when Soon-Shiong was developing Abraxane while also running a diabetes research firm with his older brother. Mylan Laboratories, a large shareholder in the firm, sued the brothers, alleging that Patrick had been using diabetes resources to develop his cancer drug. Terrence Soon-Shiong eventually sued his brother. An arbitrator, in 1999, cleared Patrick Soon-Shiong of wrongdoing.

Soon-Shiong said the dispute arose from his refusal to transplant clusters of pig cells into humans, procedures that he believed would have been unsafe.

“If you really focus on your moral compass and really ensure that you do no harm, then things will work out,” Soon-Shiong said of the episode.

There were other dust-ups and lawsuits, more allegations of conflicts.

“Patrick had a fairly negative perception among investors,” said Michael King, a biotech analyst with JMP Securities in New York, who has followed Soon-Shiong’s businesses for years. “Some felt that he had enriched himself and friends at the expense of smaller investors.”

But investors who stuck with Soon-Shiong fared well, King said.

“He managed to sell the company for a very nice valuation,” he said. “It was a win-win for everyone. And to his credit, Abraxane achieved a lot where other drugs have come and failed.”

Since then, Soon-Shiong and his team of scientists have worked on techniques tailoring cancer treatments to individual patients to try to achieve better results. He has two publicly traded firms: NantKwest, a clinical-stage immunotherapy company, and NantHealth, a diagnostics company.

Last year, Soon-Shiong’s dealings were heavily scrutinized when healthcare publication Stat published articles about a $12-million donation to the University of Utah for medical research. The university later paid NantHealth $10 million to use its diagnostic tool GPS Cancer to sequence patients’ DNA.

Critics questioned whether the donation was a vehicle to steer dollars back to NantHealth.

Soon-Shiong denied that the deal was designed to pump up GPS sales and said his company incurred a loss for doing the sequencing work for the university. He said his family's donation did not require the university to use his lab. “It’s a non-story in my mind,” he said.

A review by the Utah legislature last fall found the university had violated state laws because it didn’t put the sequencing contract out for a competitive bid. However, the audit noted the resulting research led to scientific discoveries, including identifying new gene mutations.

But the controversy wiped out much of the stock value of NantHealth and NantKwest. Once trading as high as $18.50 and $30 a share, respectively, the two stocks have slumped to about $3 and $3.75.

And Soon-Shiong received more bad publicity last fall when performer Cher sued, accusing Soon-Shiong of duping her into selling her stock in a fledgling healthcare firm for less than its value. He denied the allegations, and the suit was dropped last month.

But Soon-Shiong has earned admirers for making investments that have improved life in Los Angeles. County Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas credits Soon-Shiong for helping the county build the gleaming 131-bed Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital, which opened in 2015 in Willowbrook.

For eight years, residents of Compton, Watts, Inglewood and Lynwood had no nearby hospital. Martin Luther King Jr.-Harbor closed for acute care needs in 2007, after years of problems, including the incident in which the woman died after writhing in pain on the floor of the emergency room lobby.

Two years after the closure, Ridley-Thomas and his fellow supervisors were struggling to get a new hospital off the ground. The county needed to get the University of California regents on board so that qualified UC-affiliated doctors would practice at the hospital.

The regents “wanted this to be a financially viable project" and suggested that Soon-Shiong underwrite the project, Ridley-Thomas said.

"I called him with the request. I said, ‘We need you to guarantee this,’ and he signed the letter,” Ridley-Thomas said. Soon-Shiong agreed to pay $100 million should the county default.

"He had a game-changing effect,” Ridley-Thomas said. “He gave his commitment so there would be healthcare for the medically indigent.”

He had a game-changing effect. He gave his commitment so there would be healthcare for the medically indigent.”

— Mark Ridley-Thomas, Los Angeles County supervisor

At the 2015 ribbon-cutting ceremony for the $172-million facility, Soon-Shiong drew parallels between the disparities in healthcare in his native South Africa and in South L.A.

“Medical apartheid will end right here, the health desert will end right here,” he told the crowd.

Last year he stepped in to resuscitate six California hospitals that were on financial life support, including St. Francis and St. Vincent in the heart of Los Angeles.

Religion has played an integral role in his life. Michele is a devout Catholic, and the couple attend Catholic services. In 2016, he accompanied then-Vice President Joe Biden to meet with the Pope at the Vatican.

About a decade earlier, he and Michele showed up unannounced at Resurrection Church in Boyle Heights. One of the leaders, Sister Rose Seraphin, mistook Soon-Shiong for a mechanic and asked if he could help fix the church truck used to deliver food to the needy.

Instead, Soon-Shiong wrote her a $2,000 check on the spot and over the next month bought the church a new walk-in refrigerator, donated freezers and sent a cardboard baler to press down boxes.

“They transformed the place,” Sister Rose, now 84, said. “He has done a lot for us.”

The couple, sometimes accompanied by their son and daughter, have continued to visit the church on Thanksgiving and Christmas. Sister Rose recalled walking into the main warehouse one December and finding Soon-Shiong preparing Christmas baskets alongside other volunteers.

“We had two pallets of scallion onions and he was cleaning them with such humility,” she said. “One thing I’ll never forget … especially when I knew who he was.”

Soon-Shiong also is a familiar presence at Lakers home games, prominently sitting courtside near the players’ bench. He also enjoys playing his own pickup basketball with Nant employees, hosting a weekly game at his Brentwood home, a sprawling multi-acre compound that he built after buying up about a dozen ranch-style homes starting a decade ago and then bulldozing them. Those weekly games provide a window of calm for him — and for his executives, because they know he won’t be sending emails during the game.

Since buying Magic Johnson’s roughly 4.5% stake in the team in 2010, he has struck up friendships with players including former Lakers Kobe Bryant and Pau Gasol. He has been a season ticket holder for 25 years.

“He’s been a great partner,” said Jeanie Buss, the team owner. “He loves the Lakers and he’s inspiring to all of us. He’s always there if we need anything.”

Buss said she was touched by Soon-Shiong’s humanity when her father was nearing death five years ago. Jerry Buss was in St. John’s Health Center, a Santa Monica facility that Soon-Shiong has long supported.

“He reached out to say, ‘Is there anything that I can do?’” she recalled. “That brought me a lot of comfort during one of the hardest times in my life. He’s a wonderful man.”

Soon-Shiong’s interests are wide-ranging, and he, at times, appears restless.

He was a cutting-edge surgeon, but then moved into research. His work on diabetes segued into developing cancer treatments. He led a group in 2011 that purchased the 12,000-mile fiber-optic cable network called the Lambda Rail to link researchers, but it was shut down three years later. In 2012, he became the largest individual shareholder in the Santa Monica toy company Jakks Pacific with big plans to create lifelike animation, but the company’s value has tumbled. He also abandoned plans to build a $75-million medical research center near Phoenix as well as a bid for the Dodgers, although he is said to be in the final stages of a deal to become the largest stakeholder in soccer club D.C. United. A bid to buy California state court records in 2011 ultimately fell apart.

“I’ve never known someone who has been involved in so many different aspects of science, technology and business,” Luntz said. “His whole professional life has been very complex. It’s the product of a fertile mind. He’s one of the most brilliant people I’ve ever met.”

His whole professional life has been very complex. It’s the product of a fertile mind. He’s one of the most brilliant people I’ve ever met.

— Frank Luntz, political researcher and pollster

Soon-Shiong increasingly has been committed to protecting L.A. institutions, including the struggling hospitals, possibly with an eye toward securing his place among the city’s civic leaders. That commitment was a factor in his bid for The Times.

He first invested in The Times’ parent company, Tronc, two years ago, becoming the company’s second-largest shareholder. He repeatedly expressed interest in spinning off The Times but was told the California paper was not for sale.

But earlier this year, The Times’ management had descended into chaos. In a first for the news organization, its journalists elected to unionize. The newly installed publisher was placed on unpaid leave after revelations of sexual harassment allegations earlier in his career. The newsroom was in revolt against the new editor.

The then-chairman of Tronc, Michael Ferro, called several wealthy Angelenos, including billionaire Eli Broad and Soon-Shiong, to say he was finally ready to part with The Times. The price, Ferro said, was $500 million — a huge premium on the value that analysts had placed on the Los Angeles and San Diego papers.

Soon-Shiong didn’t hesitate at the price tag: “I view this as a 100-year plan.”

Already, he has started referring to the paper as a family business, although he declined to say whether relatives, such as his wife or his daughter, who was a summer intern at The Times in 2012 and 2013, would take on a role.

“He begins with this notion of legacy,” said Norman Pearlstine, former vice chairman of Time Inc. and a former top editor at the Wall Street Journal.

“He feels a genuine sense of wanting to do something good for the community,” he said. “He feels that he has had very good fortune being in Los Angeles — he was able to do things in L.A. that he might not have been able to do anywhere else.”

Soon-Shiong said he is excited to lead The Times in what he hopes will be a period of expansion.

“It’s very clear that there’s been very little investment in not only just the newsroom but the infrastructure of the organization,” he said. “That is what I’m going to invest in, as well as investing in hiring the best and the brightest in terms of people who have a passion for honest storytelling.”

He recognizes that he’s new to newspapering, but believes he shares a particular DNA with the editors, reporters, photographers and web producers who soon will be working for him.

“Journalists are very much like scientists in the sense that they yearn for discovery,” Soon-Shiong said. “They like to report their work. They search out the facts.”

Journalists are very much like scientists in the sense that they yearn for discovery. They like to report their work. They search out the facts.”

— Patrick Soon-Shiong

Since signing the deal in February, Soon-Shiong had been eager to meet the staff and see the newsroom. On Friday, he held a town hall in the Chandler Auditorium in the Times building, addressing the crowd of more than 300 for nearly an hour and a half. He appeared at ease, displaying an affable and jovial manner as he fielded questions and spoke about his background and vision for the newspaper.

And he drew on another science-journalism analogy.

“I think fake news is truly the cancer of our time,” Soon-Shiong said to enthusiastic applause. “I’m just going to say it: Facebook and Google really are media companies that actually capture fake news into social media or a search element. So social media is a source of metastasis of fake news.”

There is one cure for that, he said.

“The last bastion to the health of democracy are journalists,” he said. “We have to become a source of trust. That when they read something from the L.A. Times, the San Diego Union-Tribune, the California News Group, that the news … is honest, factual, fair and written with compassion and care and inspiration. We can be the beacon of light.”

Twitter: @MegJamesLAT

Twitter: @byandreachang

Times staff writers Robyn Dixon in South Africa and Scott Wilson and Thomas Curwen in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

Produced by Sean Greene

UPDATES:

April 14, 4:15 p.m.: This article was updated with details from Friday’s town hall meeting and additional comments from Soon-Shiong.

April 13, 12:00 p.m.: This article was updated with Soon-Shiong’s announcement that he planned to move the L.A. Times to El Segundo.

This article was originally published April 13 at 10:10 a.m.

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.