Wells Fargo Center gets $60-million upgrade as Bunker Hill skyscrapers grapple with competition

The Wells Fargo Center, with its granite walls soaring more than 50 stories into the air, has long been considered one of the best office addresses in downtown Los Angeles.

But its owners recently came to an unpleasant realization: Although the two-skyscraper complex atop Bunker Hill was still home to blue-chip accounting, law and financial firms, it’s hard-edged corporate vibe was just too 1980s for modern tastes.

The ground level felt isolated from the streets behind intimidating steps — redolent of cuff links and shoulder pads in an era grown comfortable with T-shirts and jeans.

Lingering with a book or sack lunch might be tolerated, it seemed to say, but not encouraged.

Contrast that with newer campus-style offices on the city’s Westside, where workers can relax around fire pits or work in a garden.

“The environment was dated,” said Bert Dezzutti of landlord Brookfield Office Properties, which acquired the center just five years ago as part of a portfolio deal estimated to be worth as much as $3 billion.

But a lot has changed in the interim, including in downtown’s Historic Core and Arts District, where a new crop of renovated buildings offers tenants a lively street scene outside.

Brookfield decided it needed to make the center’s formal three-story atrium softer and more open to the elements, a place where people would want to kick back, meet friends or perhaps work on a laptop.

The New York-based landlord has embarked on a $60-million makeover of the atrium that will create an indoor-outdoor environment dubbed Halo, with restaurants, bars and coffee shops meant to lure tenants of the entire office district out of their glass towers.

About 5,000 people work in Wells Fargo Center each day, Dezzutti said, among a Bunker Hill population of nearly 40,000 workers — more than the number of residents of Beverly Hills or West Hollywood.

The atrium makeover was designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, the same architecture firm that designed the 2.5-million-square-foot Wells Fargo Center in the 1980s.

The red granite-clad complex “is a great example of late-modern architecture that really captured the spirit of its time,” Skidmore architect Paul Danna said.

But that time was more imperious from an architectural standpoint. Top-drawer office complexes such as Wells Fargo Center and others in Los Angeles and around the country “were developed as corporate enclaves with the intent of being rather insular and secure,” Danna said.

Cultural sensibilities are shifting, the architect said, toward making offices more relaxed, including their semi-public spaces at ground level.

“Before, main lobby and plaza spaces were really corporate foyers to the space above,” Danna said. “Today, they are being reconfigured as living rooms for people who work in the community and workspaces for people who work in the building.”

Brookfield’s renovation will open up the middle of Wells Fargo Center, which was constricted with hard-to-find entrances. The owner will also try to integrate the property more smoothly with surrounding sidewalks by taking down low walls that sported signs and graphics but also “served as subtle reminders that this was private space,” Danna said.

There will be full-service and quick-service restaurants as well as vendors selling prepared foods.

Bicycle storage lockers and showers will be added for tenants, who will be provided with a phone app that will give them access to their offices and new options in Halo such as yoga, fitness classes and meditation.

Brookfield will provide programs such as lectures and concerts to create a sense of community among tenants, Dezzutti said.

There will be a tenant-only lounge with food, meeting rooms and an outdoor deck. The tenant amenities will be operated by Convene, a tenant of Brookfield’s that also manages communal work and meeting spaces for rent in Brookfield office buildings.

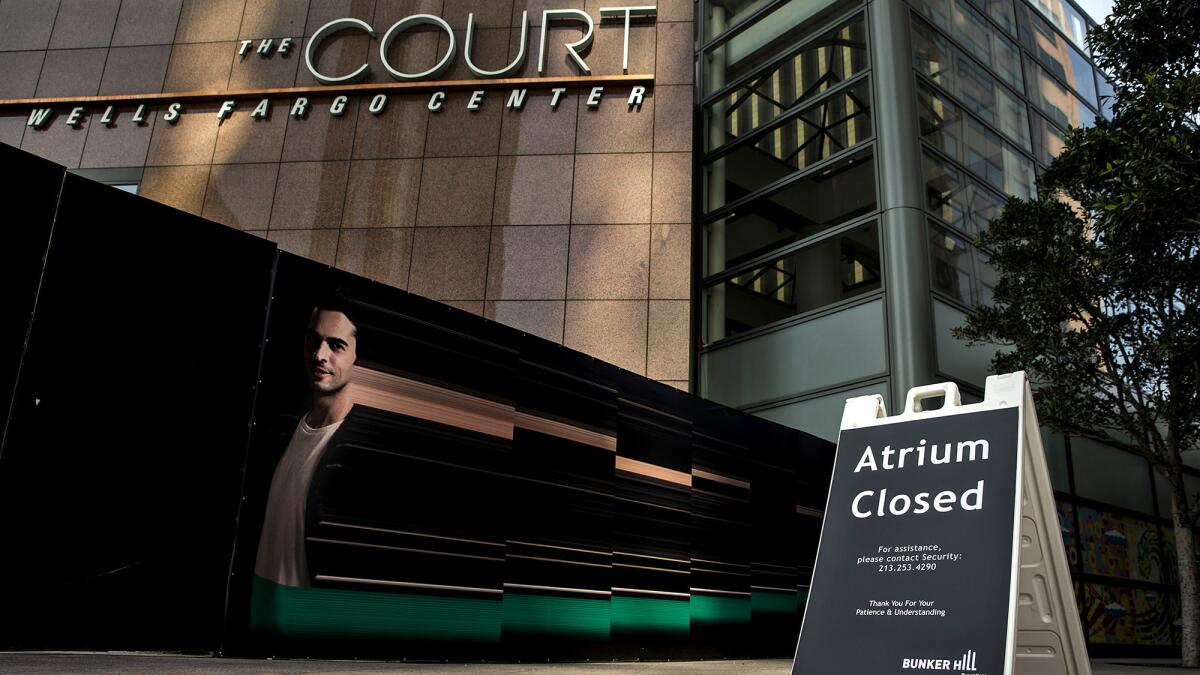

The old atrium is now being demolished, and Halo should be completed by the middle of next year, Brookfield said.

The move comes as Bunker Hill office landlords often struggle to attract tenants. Though the high-rise towers completed in the 1980s and early 1990s still evoke majesty, many companies are passing them over for personality-rich historic buildings downtown that have been renovated to modern standards.

And it’s not just firms in creative fields such as entertainment and technology that want more open, relaxed work environments, Dezzutti said. Bankers and lawyers seek them too.

“They want what Spotify wants,” he said, referring to a popular music and video streaming service expected to lease space in a rambling office and retail complex coming to the Arts District that bills itself as the future “social epicenter” of the neighborhood.

Such young companies often want open-plan, “collaborative” office space and the opportunity to spread work and leisure time with office mates outside, real estate broker Gary Horwitz of JLL said.

“What differentiates a lot of buildings is their outdoor areas,” he said. “We’re seeing more and more of that. Gathering places, maybe with beer on tap, are just really attractive.”

Brookfield’s decision to update Wells Fargo Center comes as Bunker Hill emerges from decades of formal sterility imposed when a vibrant but decaying residential neighborhood was razed in the decades after World War II and replaced with cultural institutions such as the Music Center, gleaming office skyscrapers and a few apartment buildings.

Work is set to begin there in the fall on the Grand Avenue Project, a $1-billion collection of apartments, condominiums, hotel rooms and stores designed by architect Frank Gehry as a complement to his Walt Disney Concert Hall across the street.

Among its noteworthy features, the Grand Avenue Project is slated to have numerous outdoor terraces where visitors can relax, mingle or dine.

The nearby Music Center plaza, dating to the 1960s, is getting its own multimillion-dollar makeover intended to make it more like a town square, easily accessible to passersby.

Gehry is also set to design an expansion to the adjacent Colburn School of performing arts. The Broad contemporary art museum, which opened next to Disney Hall in 2015, draws 750,000 visitors a year.

Wells Fargo Center needs to embrace the more inclusive nature emerging on Bunker Hill, Dezzutti said.

“People’s expectations have changed dramatically” when it comes to their offices, he said. “The lines are blurred between how they work and play. People want to do all those things in the same place if they can.”

Twitter: @rogervincent

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.