NFL workers’ comp victory comes at a price

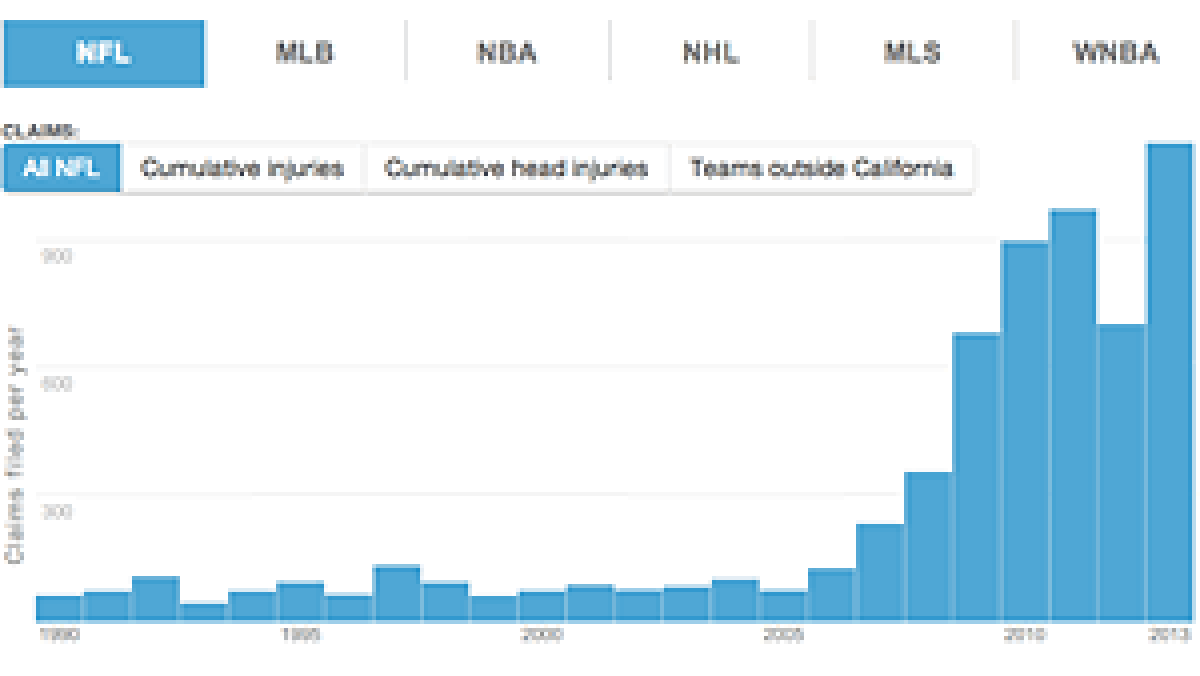

Publicity from a fight over state law prompts players across the country to file more than 1,000 injury claims before a September deadline; that could cost top pro sports leagues hundreds of millions.

Last fall, the National Football League scored a huge victory in California, helping push through a new law barring most professional athletes from filing workers' compensation claims in the state.

But that win has come at a cost.

Publicity from a high-profile battle over the legislation prompted players from around the country to file more than 1,000 injury claims just prior to a September deadline — a huge influx that could cost the nation's top professional sports leagues hundreds of millions of dollars to resolve.

In the first two weeks of September, current and retired players filed 569 claims against NFL franchises, 283 claims against Major League Baseball clubs, 113 against National Hockey League teams and 79 against NBA squads, a Los Angeles Times analysis of state workers' compensation data found.

Nearly 70% of the filings include allegations of head or brain injuries caused by repetitive trauma. Most of these athletes appeared to have never played for a California team; they filed claims based on repetitive injuries they say were sustained in part during road games played in the state. It is those claims that are now barred under the new California law.

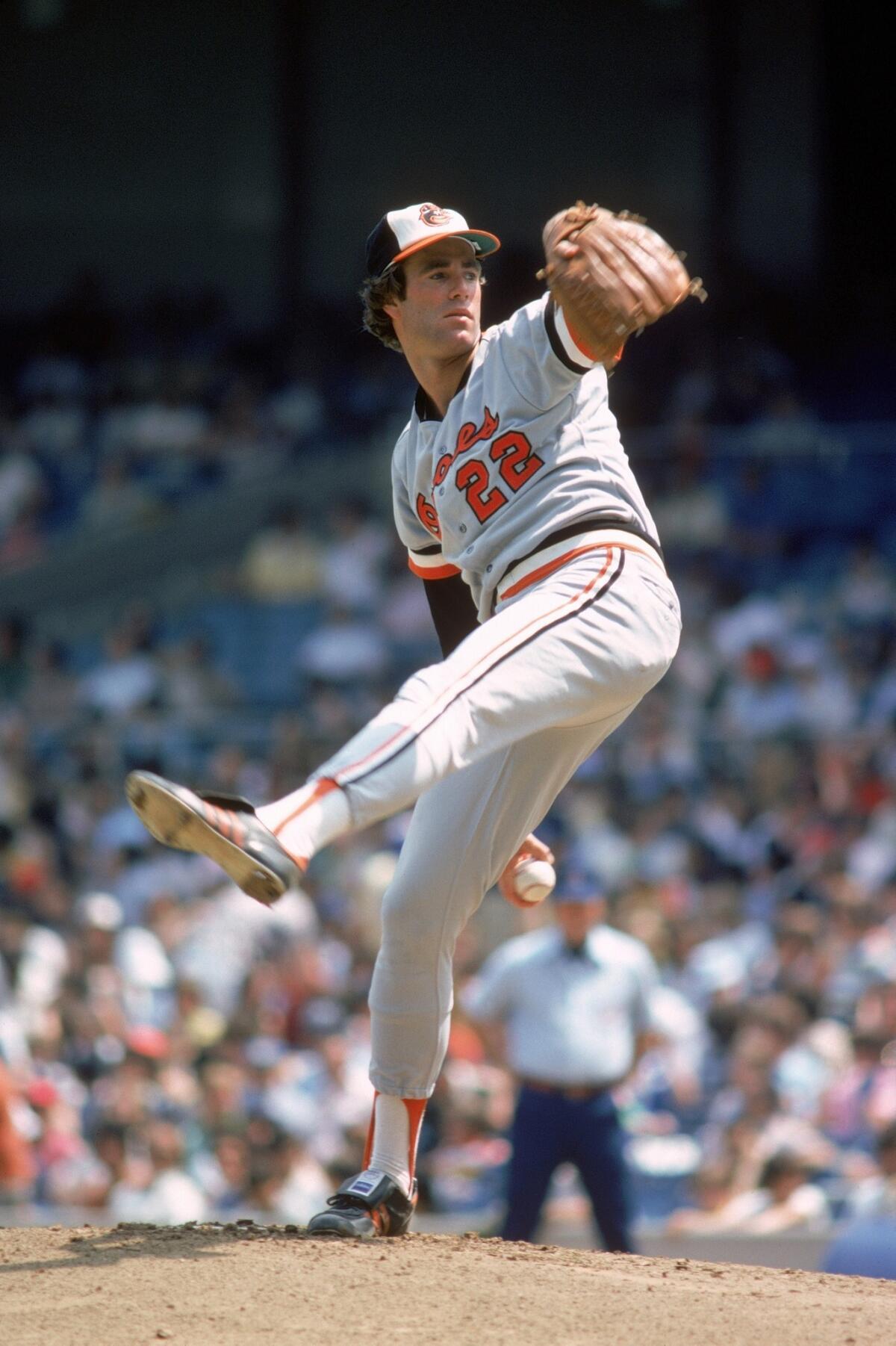

Among the athletes rushing to beat the deadline were sports legends such as Miami Dolphins quarterback Dan Marino, Baltimore Orioles pitcher Jim Palmer and Houston Rockets center Hakeem Olajuwon, as well as many lesser-known retirees, some suffering serious physical impairment. A number of active players, including San Francisco 49ers standouts Michael Crabtree and Frank Gore, also filed claims.

The six sports leagues affected by the new law — a group that includes Major League Soccer and the Women's NBA — had predicted a jump in filings before the deadline. Still, the size of the increase was surprising. The volume of claims in September was about 10 times higher than average monthly levels since 2011.

A lot of these guys have serious medical problems and need help.”— Modesto "Doc" Diaz

Tensions have been rising in recent years between athletes and owners over who should absorb the long-term costs of treating debilitating illness linked to contact sports. Earlier this month, a federal judge rejected a proposed $765-million settlement to a concussion lawsuit filed by more than 4,500 former players against the NFL on concerns that the sum wasn't enough to cover their medical care.

The workers' compensation data highlights the huge scale of the injury legacy that confronts American professional sports franchises.

Last year the leagues, led by the NFL, successfully lobbied the state legislature to pass AB 1309, which prohibits athletes who spent most of their careers playing for teams outside California from filing claims in the state. The leagues believed the law could save them from exposure to countless claims from injured athletes.

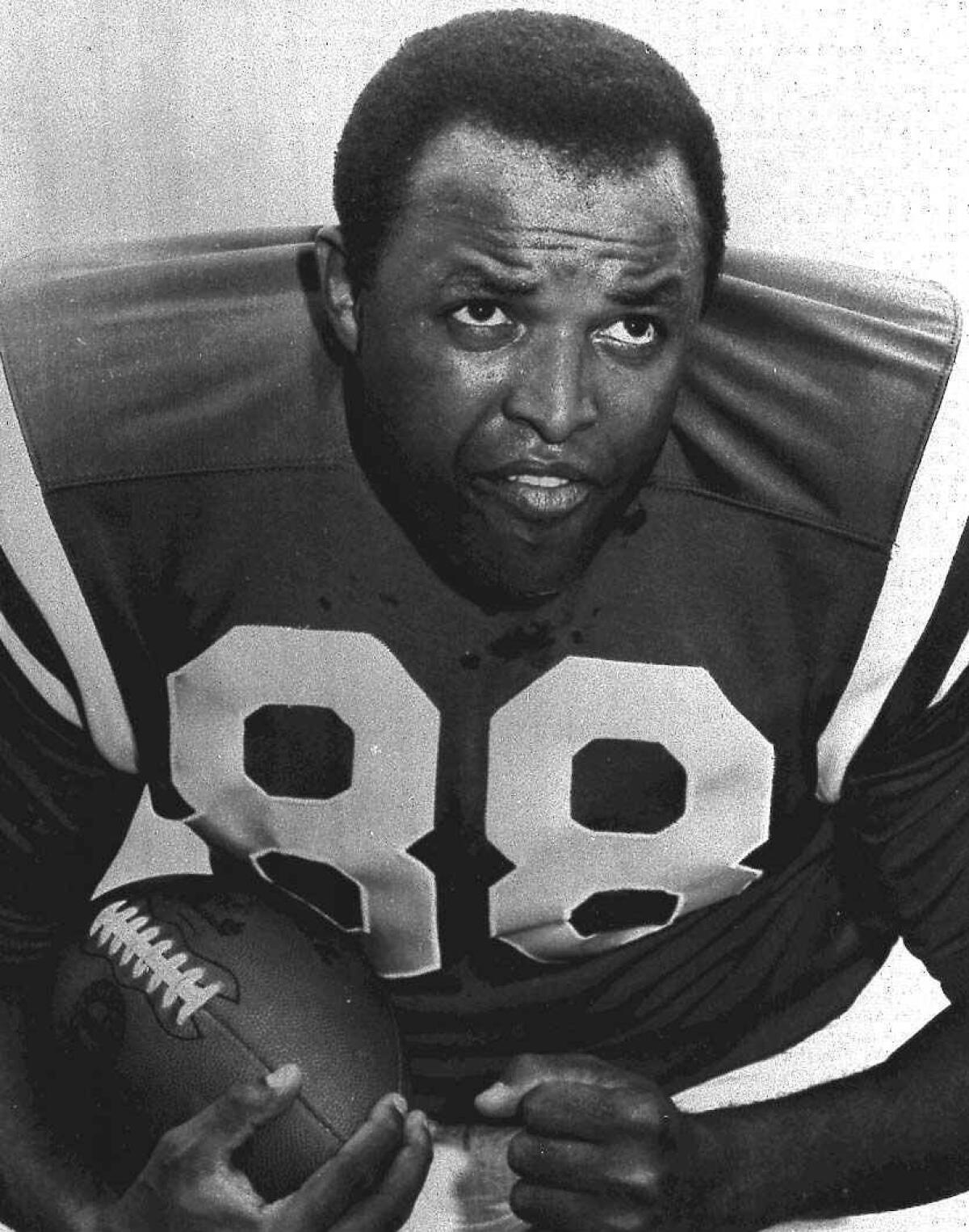

The family of Hall of Fame tight end John Mackey, who died in 2011, shown here in a 1969 file photo, filed a claim days before AB 1309 took effect. Mackey's struggles with dementia led the NFL to create a special fund for players with brain trauma. (Associated Press)

More than a third of the final batch of claims lodged before the new statute became effective Sept. 15 wouldn't have been affected by the new law, the Times analysis found. Advocates for injured athletes say that the months-long fight over the bill, which drew national attention, helped alert athletes who otherwise wouldn't have known they could seek benefits.

"There's no question that a lot of guys would never have filed if not for all the hoopla over the bill," said Modesto "Doc" Diaz, a Santa Ana attorney who specializes in representing athletes. "From my perspective, it's good news, because a lot of these guys have serious medical problems and need help."

Other athletes who managed to get in last-minute claims include NFL greats Boomer Esiason, Lynn Swann and Thurman Thomas, MLB stars Randy Johnson and Willie McCovey, and NBA legends Clyde Drexler and Gus Williams.

But filings were also made by many lesser-known athletes suffering debilitating illnesses they believe were caused by sports. Among them were two football players, O.J. Brigance and Steve Gleason, with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a fatal illness also known as Lou Gehrig's disease that some research has linked to head trauma.

Another last-minute filing came from the family of Hall of Fame tight end John Mackey, whose struggles with dementia led the NFL to create a special fund for players with brain trauma. Under California law, Mackey's family could receive up to $250,000 if his 2011 death is linked to football.

More than three-quarters of the claims filed against NFL teams in the first two weeks of September alleged head or brain injury. Half of baseball players and just over 90% of hockey players made similar claims.

The NFL and MLB both declined comment. The NBA and NHL did not respond to requests for comment.

In past interviews, the leagues said they supported the new statute because they were concerned that players were abusing California's worker-protection system.

Workers' compensation allows employees to file claims for on-the-job injuries in exchange for relinquishing the right to sue. Although claims are adjudicated in the courts, cash awards or medical care are paid for by employers or insurers, not taxpayers.

An NFL study of past filings found that the average California claim cost teams $215,000 to resolve, a number that could be far higher for players with debilitating brain disease. Unlike other states, California long permitted claims from players who did not play for in-state teams so long as they participated in at least one game or practice here. California also recognizes cumulative injuries incurred over time.

And although California has a one-year statute of limitations for claims, that restriction is waived when workers aren't properly notified of their right to file, which was the case with many players for decades. As a result, many athletes with slow-to-develop disease such as dementia turned to California when legal doors in other states had long been shut.

Hall of Fame pitcher Jim Palmer of the Baltimore Orioles was among 1,980 workers' compensation claims filed just before AB 1309, which prohibits athletes who spent most of their careers playing for teams outside of California from filing claims in the state.

Pro Bowl lineman Conrad Dobler, for example, was never employed by a California team. But his California road games made Dobler, now 63, eligible to file a cumulative injury claim in the Golden State. In 2012 a workers' comp judge in Santa Ana granted him a $120,000 award, plus lifetime medical care, paid for by the Buffalo Bills.

Starting in 2006, rising awareness of the California option led to an explosion in claims for cumulative trauma. Between January 2006 and April 2013, some 4,400 claims were filed in the state by pro athletes, seven times more than over the previous 15 years, the Times analysis found.

Two-thirds of all the claims alleging cumulative injury in that time came from players who did not name a California team as the responsible employer.

The surge led the NFL and the other leagues to push for legislative action to reduce claims volume by restricting claims to athletes who played for California teams for significant portions of their careers.

Opponents, including organized labor, called the bill a handout to wealthy franchise owners that would effectively deny care to thousands of injured athletes who couldn't file anywhere else.

But AB 1309 bill passed easily and was signed into law Oct. 8. A provision of the bill, adopted at the last minute, set an effective date retroactive to Sept. 15; any filing after that date from an out-of-state athlete would be invalid.

In anticipation of that deadline, workers' compensation attorneys scrambled to find players and file on their behalf.

Between February, when the bill was introduced, and Sept. 15, a total of 1,980 athlete claims were filed in California — compared to 1,170 in all of 2012.

San Diego lawyer Ron Mix squeezed in almost 300 athlete cases in the final month, according to state data. To get through the mountain of paperwork, he said he paid his staff triple overtime and hired numerous temp workers.

"We were working 12 to 16 hours a day, seven days a week," said Mix, a former Hall of Fame lineman for the San Diego Chargers.

The Times analysis showed that 363 of the 1,064 claims made in the first two weeks of September listed a California-based team as the employer, indicating they likely didn't need to beat the Sept. 15 deadline. In addition, a number of still-active players filed injury claims, something that rarely occurred in the past because players feared being cut by their teams.

"Everyone wanted to beat the deadline," said Mel Owens, a Laguna Hills attorney and former Los Angeles Ram linebacker. He filed more than 250 claims for athletes in the final push, according to the analysis.

Overall, between February, when the bill was introduced, and Sept. 15, a total of 1,980 athlete claims were filed in California — compared to 1,170 in all of 2012. More claims were filed in that nine-month period than any other year, by far, the analysis found.

AB 1309 put that trend to a halt: In the six weeks following the deadline, just 49 filings from all sports came in.

Although it's impossible to determine how many athletes will be barred from filing under AB 1309, attorney Mix estimates it could top 4,000. In recent months, he said he's gotten calls from about 150 athletes that he had to turn away because they missed the deadline.

But advocates for injured players haven't given up the fight.

Diaz, the Santa Ana attorney, said he's urging active players to file workers' compensation claims as soon as they happen, rather than waiting to retire, in order to preserve their standing. Eventually, Diaz said, a constitutional challenge to AB 1309 could be in offing.

"I'm keeping my eyes open for the case with the right facts so we can take this matter to court," he said. "We're not done here."

Follow Armand Emamdjomeh (@emamd) and Ken Bensinger (@kenbensinger) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More coverage

California limits workers' comp sports injury claims

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.