If GOP scales back the mortgage interest deduction, Californians would be hit hardest

Real estate agents maintain that such a move would cause a sharp downturn in the housing market. (Aug. 28, 2017) (Sign up for our free video newsletter here http://bit.ly/2n6VKPR)

For decades, the home mortgage interest deduction has been one of the most sacred of cows in the U.S. tax code.

It is particularly revered in Los Angeles and other areas with high real estate prices, where the annual tax savings can be the difference between being able to afford a house or continuing to rent.

Now,

And thousands of Californians could feel the pain.

The move comes as GOP lawmakers and

No one is talking about totally eliminating the deduction for mortgage interest. It has powerful backers in real estate agents and home builders, who maintain that such a move would cause a sharp downturn in the housing market and hurt broader homeownership efforts.

But Republicans have to target some significant tax breaks to help offset part of the lost revenue from a cut in corporate and personal tax rates.

The need to eliminate or scale back deductions increased after Republicans failed to repeal former President Obama’s healthcare law, which would have provided more budget flexibility to cut taxes.

Some liberals have long complained the mortgage interest deduction largely benefits wealthier homeowners and would like to see it limited, but they want the savings to pay for more affordable housing.

The housing industry strongly opposes efforts to place new restrictions on the deduction, arguing that would lead to lower housing prices because there would be less of a financial incentive to buy instead of rent.

At the same time, Democrats from California and other states with high housing prices are gearing up to fight any change.

“I think that harming the ability for Americans to own their home is like attacking motherhood and apple pie,” said Rep.

“I represent a district with homes that are very high-cost, so they have even more reason to be concerned about it,” Chu said.

Homeowners now are allowed to deduct interest paid on as much as $1 million of mortgage debt. Congressional Republicans and White House officials are looking at reducing the limit to $500,000, which would lead to billions of dollars more in federal revenue every year.

Homeowners still would be able to deduct interest on the first $500,000 of a mortgage, but would lose the deduction for interest paid on any amount above that level.

Most Americans would not be affected by such a change, either because they own their homes outright, their mortgages are less than $500,000, or they don’t have enough deductions to file an itemized tax return.

But in states with high earners and pricey real estate, reducing the mortgage interest deduction would force hundreds of thousands of homeowners to pay more taxes.

“Limiting the mortgage interest deduction to $500,000 hurts the high-cost areas across the country, from Boston to San Francisco, from Miami to Los Angeles,” said Gerald M. Howard, chief executive of the National Assn. of Homebuilders.

A big hit for California

California would face the biggest hit.

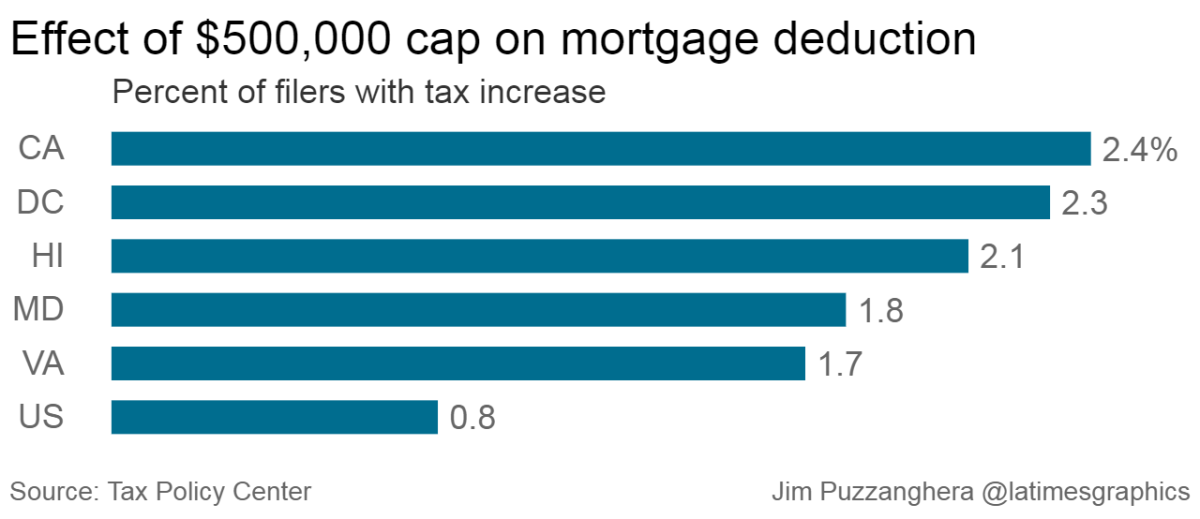

About 489,000 tax filers — 2.4% of all those in the state — would see their tax bills go up, according to an analysis by the Tax Policy Center. That’s a greater percentage than in any other state.

The average tax increase for those people would be $3,290, and it would rise in following years as the amount of deductible interest grows along with the economy. That ranks sixth, topped only by Washington, D.C., New Jersey, Connecticut, New York and Illinois, said the Tax Policy Center, which is a joint venture of the Urban Institute and Brookings Institution.

Nationwide, 1.4 million tax filers, about 0.8%, would face higher taxes, with an average increase of $3,100.

Although California accounts for about 12% of all tax filers in the country, state residents would make up more than a third of those who would have higher taxes if the cap on mortgage interest deductions were reduced to $500,000.

Such a change would also hit future home buyers, particularly in Southern California, said Geoff McIntosh, president of the California Assn. of Realtors.

“If Congress were to move forward with a cap on the mortgage interest deduction for loan amounts up to $500,000, a quarter of California’s home sales would be impacted, and those home buyers would end up paying more in taxes,” McIntosh said. “And for those in Southern California, nearly one-third would be affected.”

The effects of limiting the mortgage interest deduction would be lessened if the Trump administration and House Republicans also move ahead with plans to roughly double the standard deduction, to $24,000 for married couples filing jointly. The larger standard deduction would mean fewer people would itemize their deductions.

Republicans are in a bind because they need to offset the revenue that would be lost by slashing the corporate tax rate to as low as 15% from 35%, as well as reducing some personal tax rates.

The mortgage interest deduction is one of the most significant in the tax code. The Treasury Department estimates it will reduce federal tax revenue by about $64 billion in the 2017 fiscal year.

So limiting it would generate more money for the Treasury.

Lowering the cap to $500,000 would produce about $300 billion more in federal revenue over the next decade assuming it’s not slowly phased in, according to an analysis by the Tax Foundation. And just as with eliminating the deductibility of state and local taxes, the mortgage change would mostly hurt residents in California and other states that did not vote for Trump last year.

That restricted effect in much of the nation is part of the reason scaling back the mortgage interest deduction has political appeal to Republicans. A 2012 poll by the Pew Research Center found Americans nearly split on the idea — 47% said they supported limiting the deduction, while 44% opposed it.

Deduction limits on the table

Republicans said they are not targeting blue states and not trying to hurt the housing market.

White House spokeswoman Natalie Strom said Trump officials “intend to protect homeownership.”

But the Trump administration has released only the bare bones of a tax plan so far. Key congressional Republicans said limiting the deduction is on the table as they try to hammer out legislation they hope to unveil in September.

“House Republicans recognize that a deduction for mortgage interest is a key source of tax relief for millions of American homeowners -- and they are committed to preserving a tax benefit for mortgage interest,” said Rep.

“And we also are working to identify ways to strengthen this important provision so that a greater number of Americans can achieve the dream of homeownership,” he said.

Diane Yentel, president of the National Low Income Housing Coalition, which advocates for more affordable housing, said the ability to deduct interest on mortgages as large as $1 million means the provision benefits mostly upper-income households.

“We’re paying about $10.5 billion a year to subsidize the homes of some of the wealthiest people in the world at the same time that we have hundreds of thousands of people with no homes at all,” she said.

Wealthier homeowners benefit

The deduction distorts housing prices, making them higher because the overall cost of buying a home is reduced, said Nela Richardson, chief economist at online real estate brokerage Redfin.

“The deduction has been a sacred cow for a long time, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s good for first-time home buyers,” Richardson said. “It makes me wince a bit that we continue to subsidize the most sure-footed among us when it comes to buying a house.”

Scaling back the deduction makes sense now because the effect would be lessened because of historically low interest rates, Richardson said. But, she added, it would be “really disappointing” if the extra revenue were used for tax cuts for corporations and the wealthy instead of affordable housing.

The debate has been playing out in California, which has a separate state mortgage interest deduction that mirrors the federal one.

Interest paid on the first $1 million in mortgage debt for couples filing jointly can be deducted by taxpayers who itemize. Interest on the first $100,000 of home equity loans also can be deducted.

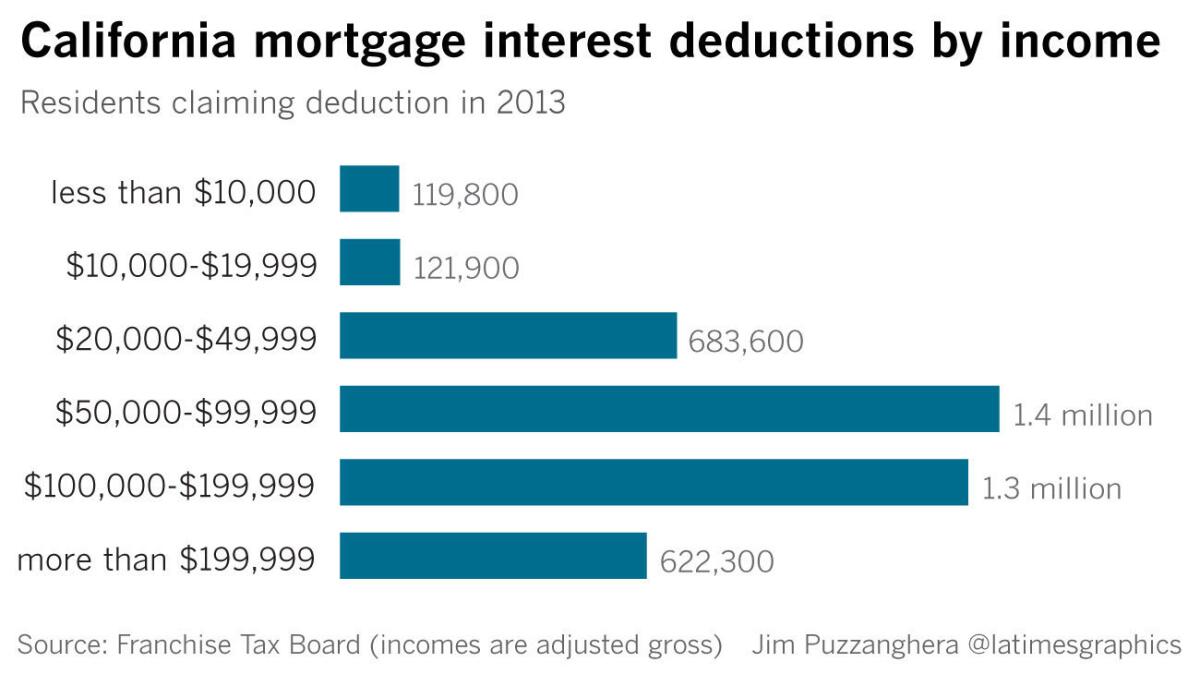

Nearly half — 46% — of the 4.2 million California residents whose tax returns reported a mortgage interest deduction in 2013 had adjusted gross incomes of at least $100,000, according to the state’s Franchise Tax Board.

The deduction reduced state revenues $3.3 billion in 2013.

Although the goal is “to provide an incentive for homeownership” the deduction “doesn’t actually make housing more affordable for homeowners,” the Franchise Tax Board said in a report on 2013 tax data, the most recent available.

The report suggested that lowering the cap on the amount of deductible mortgage interest or limiting the deduction to first-time home purchases “may bring this program more in line with its intended objectives.”

A bill in California’s General Assembly would end the tax break for second homes. The $300 million in savings would help finance low-income housing construction.

The National Low Income Housing Coalition wants to lower the federal cap on the mortgage interest deduction to $500,000 and turn it into a 15% nonrefundable tax credit.

Turning the deduction into a tax credit would allow homeowners who don’t itemize their deductions to use it.

That change also would produce more tax revenue.

An across-the-board 15% tax credit would cost federal coffers less because many of the people who use the deduction now have incomes that are taxed at a higher rate. The current deduction reduces their taxes at those higher personal tax rates, which can be as much as 39.6%.

Those changes would make the mortgage interest deduction more progressive, meaning it provides a greater benefit to lower income people than those with higher incomes, said Chenxi Lu, a research associate at the Tax Policy Center.

But Chu, who serves on the House Ways and Means Committee, said California’s high real estate costs mean limiting the mortgage interest deduction would make homeownership even more difficult for state residents.

The median home price in Los Angeles County in June was a record high $569,000, according to data firm CoreLogic. That means there were as many homes that sold above that price as below it. The median home price statewide was $470,000.

Because of those housing prices, Chu wants a study of the effects of limits to the deduction.

“The mortgage interest deduction has to do with the dreams of individual families,” she said, “and to cut this benefit for hardworking families just to pad the pockets of CEOs and large corporations is very objectionable.”

Twitter: @JimPuzzanghera

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.