In 2017, anywhere investors threw money it multiplied

Investors weren't challenged to make money in 2017. It was almost impossible to lose it.

The trading year that ended Friday was remarkable for the breadth of positive returns. Nearly every major category of investments — including U.S. stocks and bonds, foreign stocks and bonds, real estate and gold — finished the year in the black.

That would be unusual on its own, but was more so because it happened in a year when the Federal Reserve was pushing short-term interest rates up. Rising rates can be poisonous for investments across the board. But not in 2017.

True, conventional investments paled compared with the mania for so-called cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, which rocketed 1,400% to about $14,500. But in the core stock and bond portfolios held by most investors, here's a look at what drove market returns this year, and the potential implications for 2018.

U.S. stocks

Wall Street has nearly run out of superlatives to describe the year's surge in share prices. The Dow Jones industrial average ended Friday at 24,719.22, down 118.29 points for the day but up 4,956 points, or 25.1%, for 2017. The index hit a record closing high of 24,837.51 on Thursday.

Technology giants were among the market's biggest stars, driving the tech-dominated Nasdaq composite index to Friday's close of 6,903.39, up 28.2% for the year — its best return since 2013. Market leaders included Nvidia, up 81%, Amazon, up 56% and Facebook, up 53%.

But the 2017 rally broadened well beyond tech issues. The blue-chip Standard & Poor's 500 index, which slipped 0.5% on Friday to 2,673.61, rose 19.4% for the year. Including dividends, the return was 21.8%. Shares of smaller companies, which had outpaced blue chips in 2016, lagged this year but still posted healthy results. The Russell 2000 small-stock index was up 13.2%.

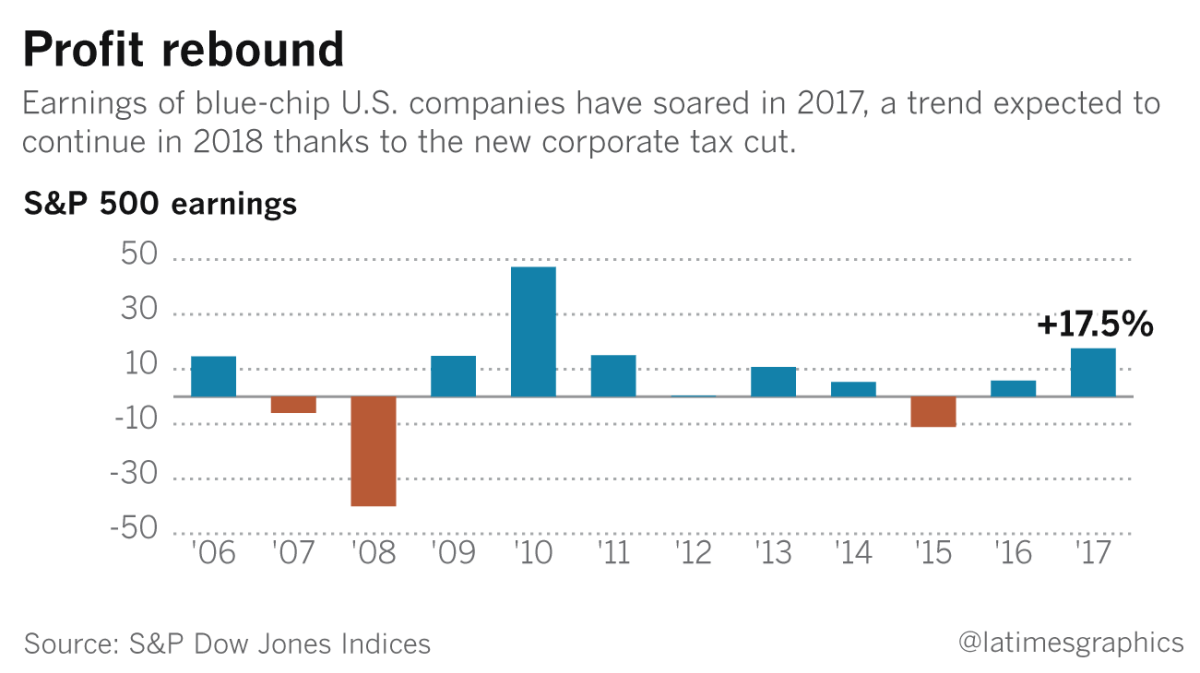

Stocks were fueled by unexpected strength in corporate earnings. Underpinned by consumer and business spending worldwide, earnings of the S&P 500 companies are projected to rise 17.6% in 2017, according to S&P Dow Jones Indices. That would be the biggest gain since the rebound that followed the financial crisis.

In the third quarter the U.S. economy grew at the fastest pace in three years, thanks partly to a jump in business investment. Also, the dollar's almost 10% drop against an index of other major currencies this year has helped make U.S. exports cheaper overseas. With that backdrop, stock bulls viewed the Fed's rate hikes more as confirmation of the economy's health than as trouble.

The Republican tax-reform plan that passed in December further stoked investor optimism. The plan's centerpiece slashes the top corporate tax rate to 21% from 35%, guaranteeing a 2018 windfall for many companies.

Some investing pros attribute much of the stock market's 2017 swagger to faith in President Trump's controversial economic policies, including tax cuts and deregulation. Joshua Brown, chief executive of Ritholtz Wealth Management and "not a fan" of Trump, nonetheless credits him with "the ignition of 'animal spirits' in the stock market and the real economy" — citing a phrase the economist John Maynard Keynes used in the 1930s to account for the "spontaneous optimism" that often drives human decision-making.

But with the average S&P 500 stock selling for a rich 18.5 times analysts' expected per-share earnings in 2018, a key fear is that there is no room in share prices for anything to go wrong — such as, say, a Trump-triggered global trade war. Mutual fund titan Vanguard Group, in its year-ahead forecast, warns that "for 2018 and beyond, our investment outlook is one of higher risks and lower returns" as the economic expansion and stock bull market both near their nine-year anniversaries.

But Brown cautions against underestimating the current momentum of the economy and markets. The history of markets over the last 200 years is "one impossible thing after another being toppled and then surpassed in rapid succession, just when everyone said no chance," he said.

A good year all around

Investors reaped positive returns in nearly all categories of domestic and foreign stocks and bonds in 2017 as well as in commodities.

| Fund | Return on investment |

|---|---|

| Emerging markets stock fund avg | Return on investment+33.7% |

| FundForeign blue-chip stock fund avg. | Return on investment25.0 |

| FundVanguard S&P 500 index fund | Return on investment21.8 |

| FundiShares Russell 2000 small-stock index fund | Return on investment14.6 |

| FundGold | Return on investment13.9 |

| FundEmerging markets bond fund avg. | Return on investment10.1 |

| FundJunk bond fund avg. | Return on investment6.4 |

| FundCalif. long-term muni bond fund avg. | Return on investment5.8 |

| FundVanguard Total Bond Market index fund | Return on investment3.5 |

| FundCommodity fund avg. | Return on investment3.1 |

| FundMoney market mutual fund avg. | Return on investment0.5 |

Sources: Morningstar Inc.; iMoneyNet

Foreign stocks

For the last few years many investment pros have been telling clients to favor foreign stocks over U.S. shares, arguing that foreign issues were bigger bargains. That advice finally paid off in 2017.

Hefty market gains in Asia and Latin America — including Hong Kong, up 36%, and Argentina, up 78% — drove the average emerging-markets stock mutual fund up 33.7%, the best showing since 2009. The average foreign blue-chip stock fund rose 25%, beating the U.S. S&P 500.

As in the U.S., earnings growth powered foreign stock markets. Money management giant BlackRock Inc. notes that year-over-year profit growth in 2017 is expected to top 10% in every major region of the world. The weak dollar also boosted foreign-market returns for U.S. investors as stronger foreign currencies translated into more dollars.

One advantage that foreign shares may have over U.S. stocks in 2018: In most of the world, including Europe and Japan, central banks are expected to maintain easy-money policies, even as the U.S. Fed continues to raise short-term interest rates.

Some analysts warn that China's economic slowdown could weigh on other emerging-market economies if it saps Chinese demand for imports, including raw materials. But Stephen H. Dover, head of equities at Franklin Templeton Investments, says many emerging markets are at a tipping point where natural resources and other exports "are no longer the primary drivers of growth and of the equity markets." Instead, those economies are relying more on their own consumers' spending and the shift toward service industries such as healthcare and entertainment.

Bonds

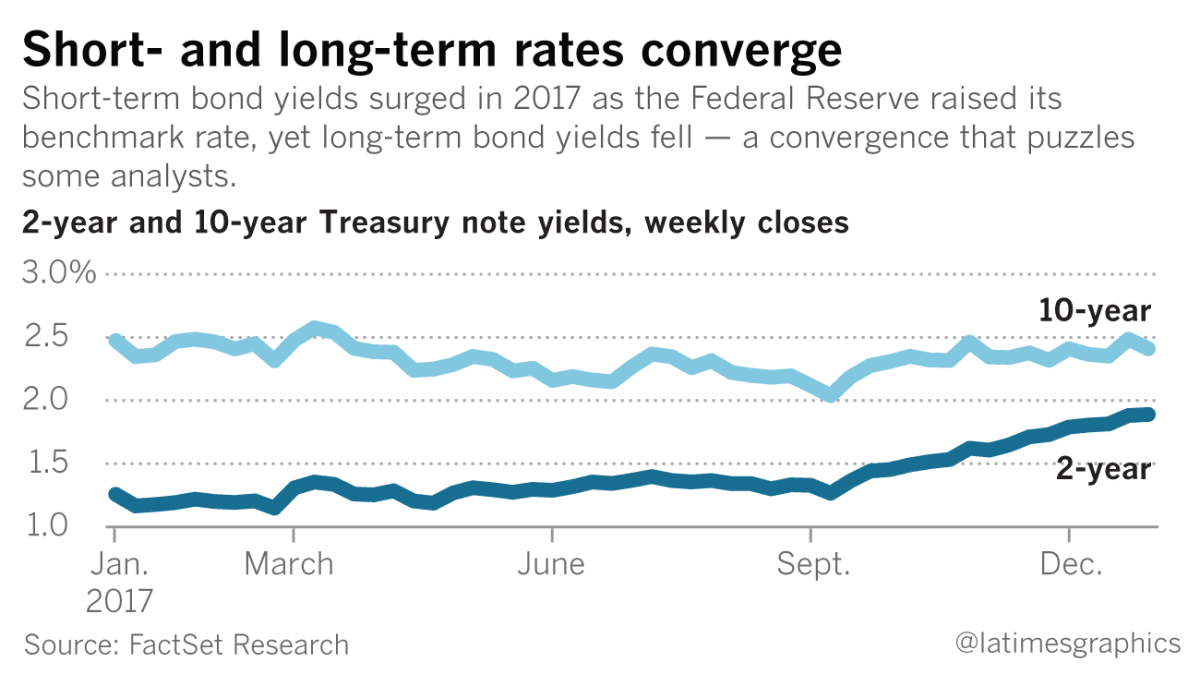

Investors who own bonds should have been braced for trouble in 2017, as the Fed raised its benchmark short-term interest rate by a quarter of a point three times — in March, June and December. Rising market interest rates can devalue older bonds that pay fixed rates.

What's more, with its target rate now set at a range of 1.25% to 1.50%, the Fed has signaled three more hikes in 2018 if the economy continues to expand.

Yet "despite the never-ending predictions about rising rates and a bond bear market, the bond market experienced another solid year of performance," notes Cullen Roche, head of financial advisory firm Orcam Financial Group.

The key: Even as the Fed boosted short-term rates, longer-term interest rates either held mostly level or declined. The yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury note ended Friday at 2.41%, down from 2.48% a year earlier. So older bonds held their value, and investors took home their interest earnings for the year.

The popular Vanguard Total Bond Market Index exchange-traded fund gained about 3.5% for the year. The average junk bond fund was up 6.4%. Emerging-market bond funds returned about 10%.

By contrast, investors who kept their savings in super-safe money market mutual funds earned just 0.5% for the year.

The crucial question for 2018 is whether longer-term U.S. interest rates can stay down even if the Fed, under new Chairman Jerome Powell, keeps raising short-term rates. That may depend on whether the economy kicks into a high enough gear to push "core" annual inflation above the Fed's 2% target level, from the current 1.7%. Bond owners fear inflation above all because it eats away at fixed bond yields.

Many analysts say that global economic growth remains moderate enough to keep overall inflation subdued. There's another force holding down longer-term bond yields: Still scarred by the 2008 financial crash, millions of investors worldwide continue to favor high-quality bonds for their relative safety. In the U.S., investors have poured a net $246 billion in new money into bond mutual funds this year, while they withdrew $193 billion from stock funds, according to the Investment Company Institute.

BlackRock believes "income-starved and safety-seeking investors" will remain hungry for bonds, keeping longer-term interest rates "well below historical averages."

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.