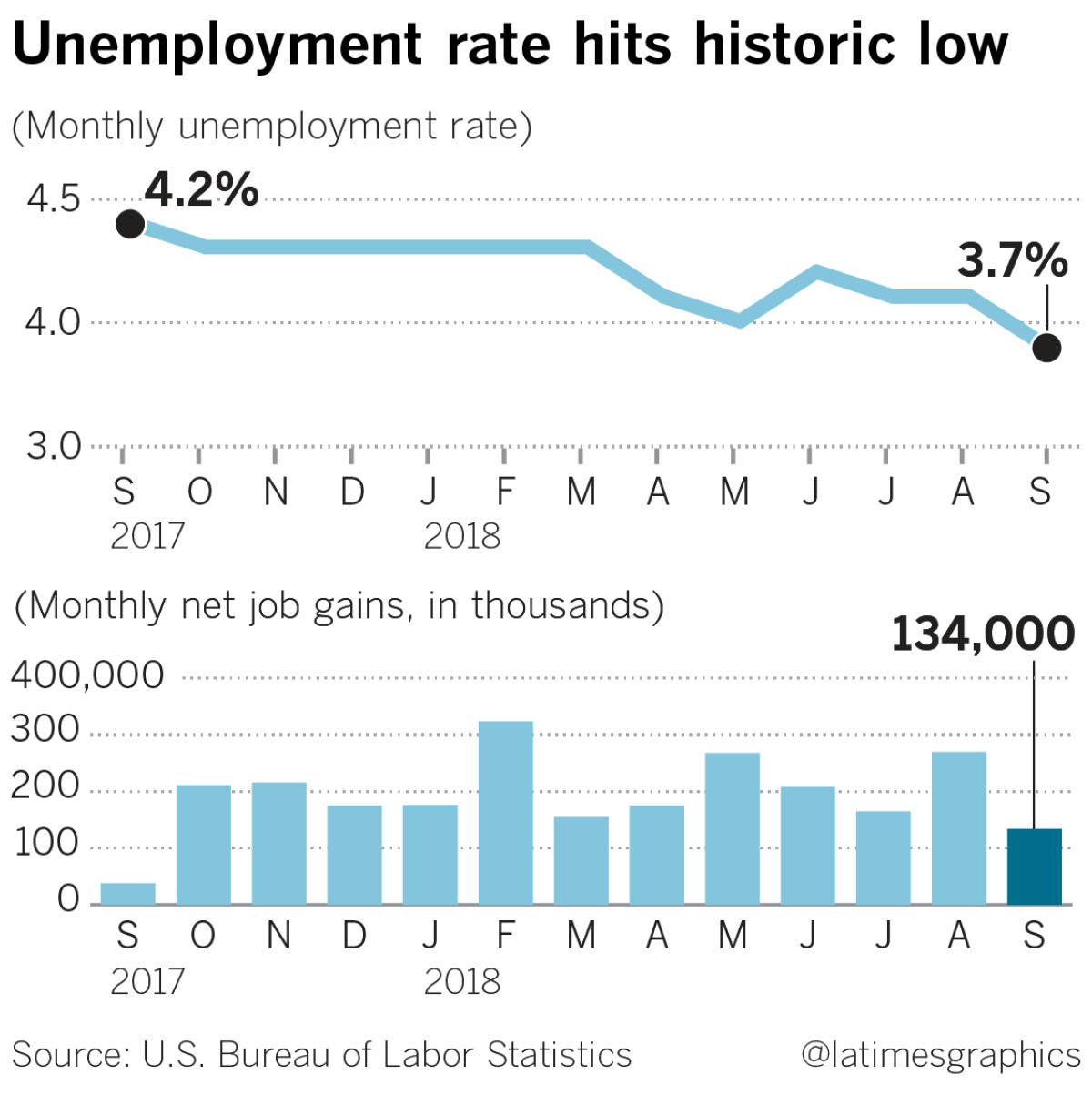

U.S. hiring and wage growth slow; unemployment hits its lowest level since 1969

U.S. employers added just 134,000 jobs in September, the fewest in a year, though the figure probably was lowered by Hurricane Florence, the Labor Department reported Friday. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate fell to 3.7%, the lowest level since 1969.

Hurricane Florence struck North and South Carolina in the middle of September and closed thousands of businesses. A category that includes restaurants, hotels and casinos lost jobs for the first time since last September, when Hurricane Harvey had a similar effect.

Even with unemployment now at a historic low, average hourly pay in September increased just 2.8% from a year earlier, one tick below the year-over-year gain in August.

September extended the longest streak of hiring on record, with millions of Americans having gone back to work since the Great Recession. Healthy consumer and business spending has been fueling brisk economic growth and emboldening employers to continue hiring. The September gain extended an 8½-year streak of monthly job growth.

The dollar and Treasury yields fluctuated after the report was released, with the 10-year rate briefly touching a fresh seven-year high.

“The markets could give this a little bit of a pass ’cause it’s not clear what impact the hurricane had at the moment. I would view this as a full-employment jobs report,” said Alan Krueger, a Princeton University economics professor who was head of the White House Council of Economic Advisors under former President Obama. “It’s going to reinforce the Fed’s path for raising rates.”

Payrolls

Revisions added a total of 87,000 jobs to payrolls in the previous two months, according to the figures, resulting in a three-month average of 190,000. Hiring data may show storm-related swings for October too, economists said.

Details across industries showed that construction payrolls grew by 23,000 jobs and manufacturing grew by 18,000 jobs. That’s consistent with other reports showing strength in such activity. Service providers increased payrolls by 75,000 workers, the lowest in a year, and retail showed a 20,000-job decline.

The Labor Department said 299,000 people weren’t at work due to bad weather, reflecting the storm’s effect. That compares with 23,000 in August, though the September 2017 count of 1.47 million — following hurricanes Harvey and Irma — was the highest since 1996.

Private employment rose by 121,000, falling short of a median estimate of 180,000. Overall government payrolls increased by 13,000.

Wages

Average hourly earnings rose 0.3% from the prior month, matching estimates, following a downwardly revised 0.3% gain the month before, the report showed. The year-over-year rise of 2.8% followed a 2.9% gain in August. Economists had penciled in some cooling in the year-over-year results, as a strong number for September 2017 wages presented a difficult comparison.

A separate measure, average hourly earnings for production and non-supervisory workers, increased 2.7% from a year earlier, after a 2.9% gain in August.

The average workweek for all private employees was unchanged at 34.5 hours. A shorter workweek has the effect of boosting average hourly pay.

Through most of the current expansion, wages have grown at a lackluster pace while other measures showed more progress, such as declines in the unemployment rate. Some companies are starting to boost wages to attract or retain workers; Amazon.com Inc. is among the latest to pledge raises.

Unemployment

The latest drop in the jobless rate puts it further below Fed estimates of levels sustainable in the long run. At the same time, some measures showed the labor market may still have some room for further improvement.

The U-6, or underemployment rate, rose to 7.5% from 7.4%. That gauge includes part-time workers who would prefer a full-time position and people who want a job but aren’t actively looking for one.

The participation rate, or share of working-age people in the labor force, was unchanged at 62.7%. The employment-to-population ratio, another broad measure of labor-market health that central bankers like to watch, rose to 60.4% from 60.3%.

Though better prospects for employment are helping to draw in people from the sidelines of the job market, boosting the participation rate, economists anticipate that retiring workers will put downward pressure on participation over coming years.

The outlook

Consumers, business executives and most economists remain optimistic. Measures of consumer confidence are at or near their highest levels in 18 years. Retailers have begun scrambling to hire enough workers for what’s expected to be a robust holiday shopping season. A survey of service-sector firms, including banks, hotels and healthcare providers, found that they are expanding at their fastest pace in a decade.

Americans have continued spending steadily and appear to be in generally stable financial shape. Households are saving nearly 7% of their incomes — more than twice the savings rate before the recession. That trend suggests that a brighter economic outlook hasn’t caused consumers to recklessly build up unsustainable debt.

During the April-through-June quarter, the U.S. economy expanded at a 4.2% annual rate, the best in four years. Economists have forecast that growth reached a 3% to 3.5% annual rate in the July-September quarter.

The economy does show some weak spots. Sales of existing homes have fallen over the last year. Increasingly expensive houses, higher mortgage rates and a shortage of properties for sale are slowing purchases. Auto sales have also slumped.

Other threats loom too. Borrowing costs for businesses and consumers are rising. Pointing to the economy’s health, the Federal Reserve last week raised the short-term interest rate it controls and predicted that it would continue to tighten credit into 2020 to manage growth and inflation. Over time, higher borrowing costs make auto loans, mortgages and corporate debt more expensive and can eventually slow the economy.

President Trump’s trade fights also weigh on the economy, though the effect on hiring probably won’t likely be felt until next year, economists say. The Trump administration has imposed tariffs on imported steel and aluminum as well as on about half of China’s imports to the United States. Most U.S. businesses will try to absorb the higher costs themselves, at least for now, and avoid layoffs, economists say.

Still, should the tariffs remain fully in effect a year from now, approximately 300,000 jobs could be lost by then, according to estimates by Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics.

Rugaber writes for the Associated Press. Chandra writes for Bloomberg.

UPDATES:

7:20 a.m.: This article was updated with additional figures about payrolls, wages and unemployment and with comment from economics professor Alan Krueger.

This article was originally published at 5:55 a.m.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.