Borrow $5,000, repay $42,000 — How super high-interest loans have boomed in California

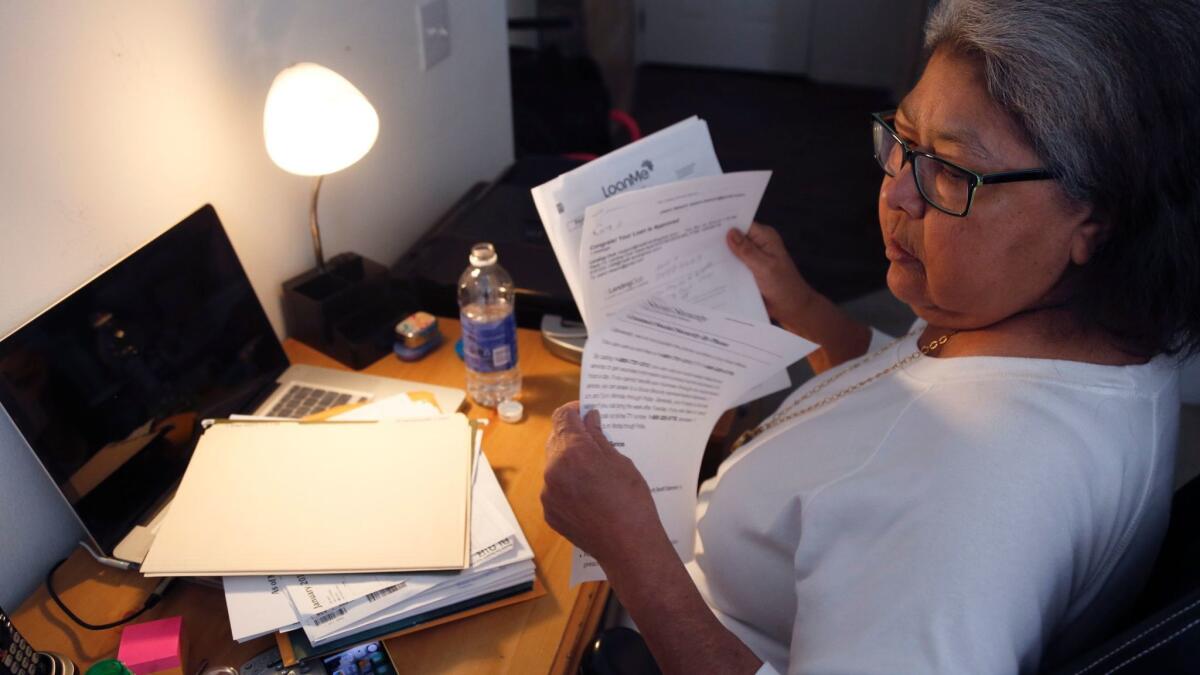

JoAnn Hesson, sick with diabetes for years, was desperate.

After medical bills for a leg amputation and kidney transplant wiped out most of her retirement nest egg, she found that her Social Security and small pension weren’t enough to make ends meet.

As the Marine Corps veteran waited for approval for a special pension from the Department of Veterans Affairs, she racked up debt with a series of increasingly pricey online loans.

In May 2015, the Rancho Santa Margarita resident borrowed $5,125 from Anaheim lender LoanMe at the eye-popping annual interest rate of 116%. The following month, she borrowed $2,501 from Ohio firm Cash Central at an even higher APR: 183%.

“I don’t consider myself a dumb person,” said Hesson, 68. “I knew the rates were high, but I did it out of desperation.”

Not long ago, personal loans of this size with sky-high interest rates were nearly unheard of in California. But over the last decade, they’ve exploded in popularity as struggling households — typically with poor credit scores — have found a new source of quick cash from an emerging class of online lenders.

Unlike payday loans, which can carry even higher annual percentage rates but are capped in California at $300 and are designed to be paid off in a matter of weeks, installment loans are typically for several thousand dollars and structured to be repaid over a year or more. The end result is a loan that can cost many times the amount borrowed.

Hesson’s $5,125 loan was scheduled to be repaid over more than seven years, with $495 due monthly, for a total of $42,099.85 — that’s nearly $37,000 in interest.

“Access to credit of this kind is like giving starving people poisoned food,” said consumer advocate Margot Saunders, an attorney with the National Consumer Law Center. “It doesn’t really help, and it has devastating consequences.”

These pricey loans are perfectly legal in California and a handful of other states with lax lending rules. While California has strict rules governing payday loans, and a complicated system of interest-rate caps for installment loans of less than $2,500, there’s no limit to the amount of interest on bigger loans.

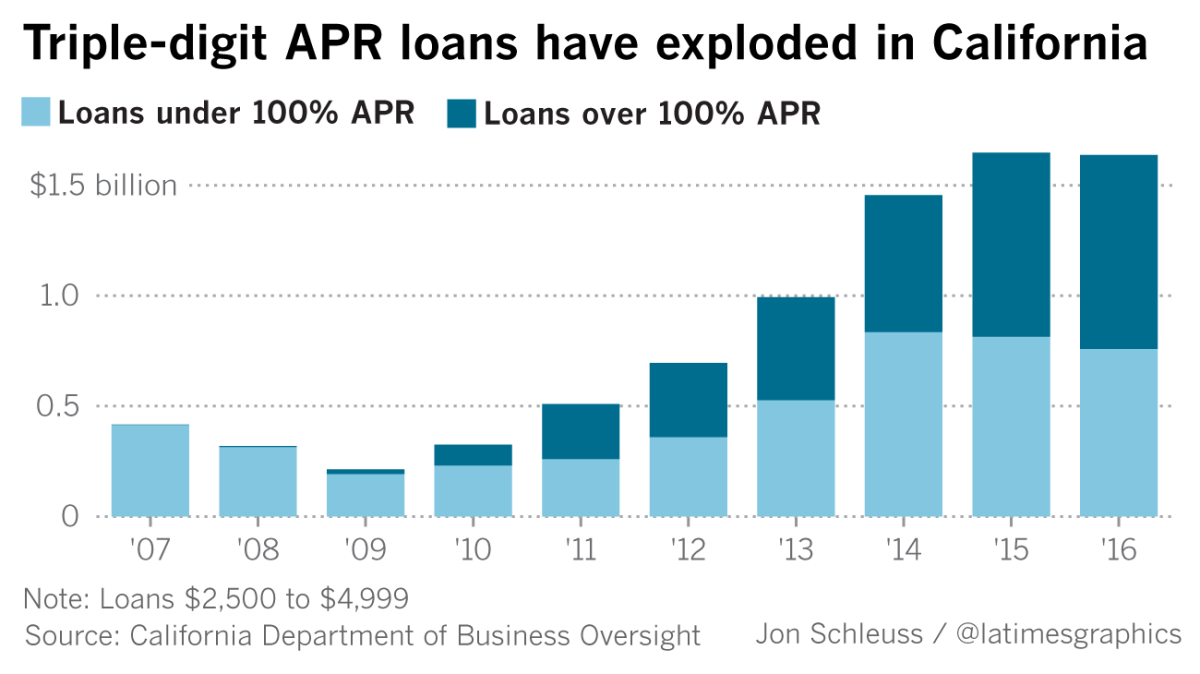

State lawmakers in 1985 removed an interest-rate cap on loans between $2,500 and $5,000. Now, more than half of all loans in that range carry triple-digit interest rates.

In 2009, Californians took out $214 million in installment loans of between $2,500 and $5,000, now the most common size of loan without a rate cap, according to the state Department of Business Oversight. In 2016, the volume hit $1.6 billion. Loans with triple-digit rates accounted for more than half, or $879 million — a nearly 40-fold increase since 2009.

The number of loans between $5,000 and $10,000 with triple-digit rates also has seen a dramatic 5,500% increase, though they are less common. In 2016, loans of that size totaled $1.06 billion, with $224 million carrying rates of 100% or higher.

Many of the loans can be tied to just three lenders, who account for half of the triple-digit interest rate loans in the popular $2,500-to-$5,000 size range. LoanMe, Cincinnati firm Check ‘n Go and Fort Worth’s Elevate Credit each issued more than $100 million in such loans in 2016, as well as tens of millions of dollars of loans up to $10,000 with triple-digit APRs.

Lenders argue they need to charge such high rates because the majority of these loans are unsecured: If borrowers stop paying, there are no assets for lenders to seize.

“Lenders don’t have a meaningful way to recover from a customer who walks away from it,” said Doug Clark, president of Check ‘n Go. “There’s a segment of the population that knows that and has no intention of paying us.”

For these borrowers, pawn shops and local storefront lenders used to be the most likely options, but those businesses can’t match the volume or convenience of today’s online lenders, which can reach millions of potential borrowers on the internet.

Many banks don’t offer personal loans at all — and certainly not to customers with weak credit looking for fast cash. After the financial crisis, banks reined in their credit card offers and stopped offering mortgages and home equity loans to customers with bad credit.

Additional regulation or interest rate caps would further cut those individuals out of the financial system, lenders argue.

“Unfortunately, banks and other traditional lenders refuse to make needed loans to a large segment of the population,” LoanMe executive Jonathan Williams wrote in an emailed statement. “We believe that these borrowers should be given the option to borrow at these higher interest rates rather than lose access to all credit.”

The cap on the size of payday loans also has played a role. In California, after fees, the most a customer can walk away with is $255.

Clark of Check ‘n Go, which for years offered only payday loans, said many of his customers switched to installment loans once the company started offering them in 2010.

“Consumers need larger amounts and more time to pay,” Clark said. “Demand was there.”

There’s a lot of room between $255 and $2,500. But many lenders — like LoanMe, Elevate and Check ‘n Go — simply choose not to offer loans in the middle, as they are subject to rate caps.

Marketing deluge

High-cost lenders attract consumers in part by spending heavily on advertising, bombarding Californians with direct mail, radio jingles and TV ads promising easy money fast. LoanMe alone spent $40 million on advertising in California in 2016, according to its annual report to the Department of Business Oversight.

In one ad, LoanMe promised “from $2,600 to $100,000 in as fast as four hours with no collateral — even if you’ve had credit problems.”

Say you get a $2,600 loan at an annual interest rate of 179%. You agree to pay it back in monthly installments over the next four years. In all, how much will you pay?

by month 32

by month 43

Sample loan from LoanMe with 2,600 principal, 179% APR over 47 months.

Lisa Servon, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania who worked at a check-cashing store and a payday lender while researching her recent book — “The Unbanking of America: How the New Middle Class Survives” — said consumers with an urgent need for money aren’t in a position to shop around or wait even a few days for an approval.

“How much time from the moment I apply to the moment I have money in my hand?” she said. “That’s what people want to know.”

Caren Jefferson found herself in just such a situation 2½ years ago. The 50-year-old South Los Angeles resident, who had uterine cancer, was frequently overdrafting her bank account and desperate to pay bills. She estimated it took 24 hours or less for LoanMe to deposit $3,000 into her bank account.

Jefferson said she wasn’t told that the loan carried a 135% interest rate or that after an initial payment of $267 she would owe $351 a month for just shy of four years — though she clicked quickly through the online application without reading much of it.

A real estate escrow officer, Jefferson made only one payment before she started overdrafting again. She told LoanMe’s customer service department that she had made a “big financial mistake.”

“Being desperate for money may lead one to make a bad/hasty decision,” she wrote the company in October 2015, according to a letter contained in a lawsuit she filed alleging unfair debt collection practices by LoanMe. “I have to rob Peter to pay Paul and someone will go unpaid.”

Many consumer advocacy groups consider these loans predatory by nature, with desperate borrowers taken in by aggressive marketing and promises of quick cash.

“They’re exploiting people’s financial hardships,” said Liana Molina of the California Reinvestment Coalition. “You can’t make a rational decision when you’re in a moment of crisis.”

What’s more, advocates argue that installment loan companies do little to determine whether borrowers can repay a loan, because it’s just not that important to them.

“As long as the borrower pays long enough before defaulting, a high-rate installment loan will be profitable,” the National Consumer Law Center said in a 2016 report.

If a borrower, such as Jefferson, makes only a few payments, a lender is certainly losing money. But if Jefferson had made a year’s worth of payments, LoanMe would have received $4,129, about $1,000 more than she borrowed — and Jefferson would still be on the hook for more than $12,000 in payments.

Many lenders, including LoanMe, Elevate and Check ‘n Go, do not charge a prepayment penalty, so borrowers can save thousands of dollars if they pay off their loans early.

Al Comeaux, a spokesman for Elevate, pushed back against the notion that lenders don’t care if borrowers can’t pay back their loans. His company won’t lend to customers whose loans are charged off, and Comeaux said Elevate wants to try to keep its customers.

In part, that’s because new borrowers are expensive. The company spends as much as $300 on advertising and other measures to bring in new customers. Return borrowers are cheaper, less prone to fraud and potentially more profitable, even though they generally pay lower rates.

What’s more, Elevate loans, on average, are scheduled to be repaid in 14 months, according to the company’s report to California regulators.

But many lenders allow much longer terms, increasing the likelihood that borrowers will pay for years and still end up owing.

LoanMe’s loans issued in 2016 were scheduled to be repaid in just under five years on average, according to its state report.

Borrowers often need to provide only basic personal information, such as a name, address and Social Security and checking account numbers. Lenders will use bank records and online databases to check income and creditworthiness.

Ken Rees, chief executive of Elevate, said his firm’s borrowers have enough income — $72,000 annually on average in California — to make monthly loan payments and meet their other obligations.

“Our customers have integrity and want to pay off their loans, but they may have things outside their awareness or control that will affect their ability to repay,” he said, noting factors such as a job loss, illness or divorce. “There are limitations to what you can do, even with advanced analytics.”

In the case of Hesson, the LoanMe borrower who has diabetes, it might not have taken advanced analytics to know she’d run into trouble.

When Hesson applied for her $5,125 loan in May 2015, she had just received the last monthly payment from a long-term disability insurance policy. Without that $1,900, she had income of about $2,900 a month from Social Security, alimony and a small pension.

Her rent at a seniors-only apartment complex plus utilities and monthly payments for two larger loans totaled about $2,600.

LoanMe payments added $495, bringing her total obligations to $200 more than her monthly income. And that’s without even considering her medical bills, or food, cable, internet access and other miscellaneous expenses.

In an emailed statement, LoanMe’s Williams said bank statements and a credit check indicated that Hesson had enough income after other loan obligations to make her monthly payments. It’s not clear whether LoanMe considered basic living costs or knew Hesson’s income had recently changed. Williams did not respond to follow-up inquiries by The Times.

“LoanMe employs a rigorous underwriting process that strives to ensure that borrowers can, in fact, afford their repayment obligations — with full consideration of their other debts,” Williams wrote, adding that it’s “patently untrue” the company makes loans to people who can’t afford them.

Molina of the California Reinvestment Coalition said that some lenders are not doing even the most rudimentary underwriting.

“If your income can’t withstand the debt, that’s not the right thing to do,” she said.

Hesson knew she did not have the money to repay LoanMe. But she was hoping the loan would tide her over until she could qualify for an additional federal pension — which ended up being denied.

“I didn’t like not paying bills,” she said. “But they made it so easy.”

Repayment squeeze

Advocates say Hesson’s story has become common over the last several years.

Leigh Ferrin, an attorney at the nonprofit Public Law Center in Santa Ana, said about 1 in 3 bankruptcy cases that crosses her desk has a high-interest installment lender as a creditor.

“We see loans with 90% APR, 100%, 130% — that’s the new normal, which is kind of depressing,” she said.

When borrowers stop paying, lenders say they have little recourse to get the money they are owed — though that doesn’t mean they don’t try.

Jefferson, the LoanMe borrower, asked for a settlement or deferred payments, telling the company she hoped to provide a Thanksgiving meal and Christmas presents for her 5-year-old granddaughter.

“I am trying to make it so I can pay you and still live,” she wrote to LoanMe.

She said the company’s customer service representatives told her they didn’t offer settlements or modifications. One, she said, even scolded her for taking out a loan “if you didn’t know what you were doing.”

Collection calls came as many as 15 times a day on her cell, land line and at the office. Jefferson said she blocked LoanMe’s number, only to have the Orange County company call with Los Angeles area codes.

“I was going to bed and waking up to LoanMe,” she said.

After Jefferson hired an attorney, she said, LoanMe changed its tune and offered a loan modification.

Williams said the company offered Jefferson seven “offers of assistance” starting the month she stopped paying, which would have been before she hired an attorney.

He said Jefferson ignored or declined those offers. The company also said that interest rates and loan terms are “prominently disclosed” and that Jefferson provided a document that showed monthly net income of approximately $4,000 and monthly debts of $822.

But according to a bank statement reviewed by The Times, Jefferson took in $3,165 from her job and child support during the month before she got the loan, and had racked up nearly $2,000 in overdraft fees in the first six months of 2015.

LoanMe never sued Jefferson to recover money owed, but that is not always so.

In 2016 and 2017, LoanMe sued more than 3,000 borrowers in Los Angeles County small claims court, seeking repayment.

And in numerous bankruptcy cases, LoanMe has gone after borrowers alleging they either took out loans with no intent to repay them or were insolvent at the time they applied for loans — something good underwriting might catch.

Over the last two years, LoanMe has been listed as a plaintiff in 22 California bankruptcy cases, challenging some part of the proceeding. In one San Diego case filed last July, the company said the customer borrowed $5,100 at an APR of 106%, made a single payment, then filed for bankruptcy protection.

LoanMe’s attorneys argued that the debt should not be discharged because the borrower “knew or should have known he had no ability to repay the loan and/or was insolvent at the time the loan was obtained.”

The company’s court filing includes a copy of the borrower’s loan application, which indicates he told the company he had monthly income of $2,700 — and zero monthly expenses.

Rees of Elevate says his company makes collection calls and sells loans to third-party collection agencies — but it generally does not take legal action against borrowers. Between 20% and 25% of Elevate’s loans are charged off, and the company stops trying to collect.

“In nonprime, there is a real chance people will not be able to pay off the loan,” Rees said. “So you price the stated APR appropriately, and if the customer does have stresses, you don’t pile on.”

Rees said among Elevate borrowers in California who repay their loans in full, 99% pay early, so the company rarely collects as much interest as the rates and terms suggest.

At Orange County-based CashCall, an early player in the market for these loans, about 40% of borrowers defaulted and 50% paid early, according to written testimony by its chief financial officer in a long-running court case over the company’s interest rates.

With steep interest rates, the loans can be profitable despite the high number of defaults and early payoffs. But they can also lead to big losses.

CashCall lost money in 2003 and 2004 when the business was starting out, according to financial reports. Although it made a total of $39.6 million in 2005 and 2006, the company lost $25.6 million in 2007 as default rates climbed in the run-up to the recession.

Elevate, which went public last year, lost a combined $42.3 million in 2015 and 2016, though it was on pace for a profitable 2017, according to its most recent SEC filings.

Reform challenges

One thing lenders and advocacy groups agree on: There is demand for these loans, driven by low wage growth, climbing housing costs, catastrophic medical bills and a lack of job security — factors that have kept many Americans on the financial edge.

A May report from the Federal Reserve found that about 25% of American adults can’t cover all of their monthly bills, and 44% say they don’t have enough savings to cover an unexpected expense of $400. Nearly a quarter said they had paid an unexpected medical expense over the last year, and more than 40% of those — representing about 24 million Americans — said they were still paying debt related to those expenses.

That’s why lenders say their products are needed to help cash-strapped Americans make ends meet.

Consumer advocates say super-expensive debt is not the solution.

This gets to a central question: Should interest rates and underwriting be more closely regulated? Cracking down would probably mean fewer loans. But high demand could push borrowers to unregulated lenders, including those affiliated with Native American tribes. Tribal lenders argue that they are not subject to state lending laws and can charge whatever the market will bear.

“A lot of academics will say these loans should be illegal, but it’s not that simple. Some people who take out these loans say they’re glad they did. Others will say they wish these things didn’t exist,” said Servon, the University of Pennsylvania professor. “The million-dollar question is, is expensive credit better than no credit at all?”

For John Jeon, the answer was yes.

A year ago, he lost a seasonal job at a West Hollywood hotel and needed cash to pay rent and a medical bill.

With a poor credit score and limited options, he turned to Elevate.

He said he originally wanted only $1,500, but Elevate doesn’t offer loans that small and approved him for $3,000 at 224% APR.

The 28-year-old took it, thinking the extra money would give him time to find a steady job — which he eventually did as a manager of a Koreatown seafood restaurant. He also worked to pay off the loan two months early.

“The nature of this loan,” Jeon said, “it’s not good to be making minimum payments.”

Under new leadership installed by President Trump, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau may seek to pull back new payday loan rules, dimming the prospects of federal guidelines for installment lenders.

In California, state lawmakers have had little success reining in high-cost lenders.

Last year, state Assemblyman Ash Kalra (D-San Jose) proposed a bill that would have capped interest rates at 24% for all loans of $2,500 or more, calling triple-digit APRs “an abusive practice.” Kalra later pulled the bill and coauthored another that would also have put a cap on rates for loans of more than $2,500 by expanding a state pilot program that now governs smaller loans.

That bill, too, stalled. A handful of lenders — including Elevate and Check ‘n Go parent Axcess Financial — and industry trade groups spent more than $300,000 on lobbying against those and other bills last year.

Kalra said he plans to try again.

“A whole bunch of profits are being made off the backs of poor and working-class families,” he said. “I think ultimately it comes down to the political will of the Legislature to stand up to these interests.”

Follow me: @jrkoren

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.