Career coach: Why companies should care about work-life balance

Recently, there have been a number of stories highlighting practices at companies that have or have not reinforced having both a job and a family (life). Take Netflix, which began offering new parents unlimited paid leave for a year, allowing them to take off as much time as they want during the first 12 months after a child’s birth or adoption. The employees can return to work on a full-time or part-time basis, and even take additional time off later in the year if needed.

Netflix said it would keep paying them normally, eliminating the need to switch to disability leave. Of course, there has been criticism, most notably that the policy only applies to salaried employees, not hourly workers.

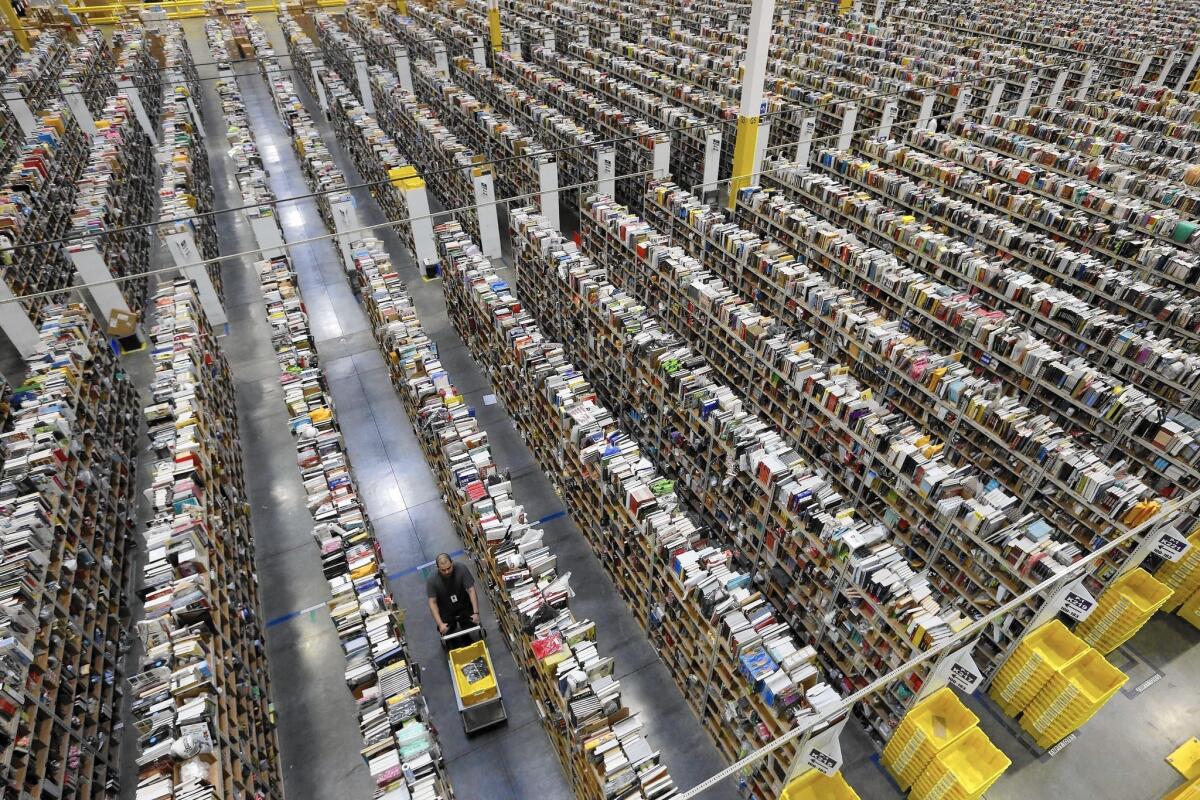

Then there was the recent coverage of Amazon workers who have complained about a punishing work culture in which people work nights and weekends, leaving little if any time for employees to even think about having families. Why is all of this important? People are struggling to figure out how to fit everything into their lives.

How do they manage work, families, community and leisure? And if they are part of the “sandwich” generation (i.e., people in their 40s and older), they are also responsible for bringing up their own children and for the care of their aging parents. They are being squeezed from every direction — from work demands to do more faster, from families, from communities who want them to be more involved, and the list goes on.

And they want to be successful at all of these facets of their lives. Just ask people how they want to be remembered when they die. Many don’t mention work as the No. 1 thing they want to be remembered for. Instead, they mention their families, their communities and the impact they want to have on the lives of others.

Yet it seems that our workplaces are increasingly being designed so that it is harder for people to manage all the parts of their lives. Researchers have shown that employees continually argue that work intrudes on their personal time, has forced them to miss important life events and made them distracted when they are with their families.

In the United States, the Family and Medical Leave Act was adopted in 1993 and was intended “to balance the demands of the workplace with the needs of families.” The act allows eligible employees to take up to 12 workweeks of unpaid leave during any 12-month period to attend to the serious health condition of the employee, parent, spouse or child, or for pregnancy or care of a newborn child, or for adoption or foster care of a child. To be eligible, an employee must have been worked at least 1,250 hours over the previous 12 months at the firm, and work at a location where the company employs 50 or more employees within 75 miles.

As a result of the many conditions attached to eligibility for leave under the FMLA, many American workers find themselves ineligible to take job-protected leave. Some researchers have indicated that only about 60% of private sector workers are covered. In addition, since FMLA does not come with pay, even fewer employees can afford to take the time off.

Compare this to other advanced nations, which provide three or four months paid leave to parents and also offer paid sick leave, generous vacation time and limits on how many work hours employers can demand. The FMLA could be expanded by the FAMILY Act — the Family and Medical Insurance Leave Act, a federal paid-leave bill introduced in March. This would allow employees to receive a portion of their pay no matter where they live or work.

So while we have some policies in place, they don’t cover everyone, and even employees who are covered are often worried about actually taking leave if they have to forgo pay. Some are anxious about using a firm’s family work policies for fear of being turned down for promotions and other perks; for being seen as “not committed.” The pressure to perform at work is so intense that some millennials are simply opting out of having children. And older employees are increasingly feeling unable to meet everyone’s demands.

Sure, we want workers to be 100% committed. But at what cost? It’s called human capital for a reason. Maybe we should remember the “human” part as we come up with company policies that meet employers’ needs for quality and productivity and at the same time meet employees’ needs for a balanced life

Joyce E.A. Russell is vice dean at the University of Maryland’s Robert H. Smith School of Business and director of its Executive Coaching and Leadership Development Program. She is a licensed industrial and organizational psychologist. She writes a weekly Career Coach column for the Washington Post. She can be reached at [email protected]..

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.