‘Factory Man’: how a Virginia furniture maker took on China

Most people in business have a story about how China has changed their industry, how over the past 30 years it has upended supply chains and grabbed daunting market share. But very few have the sort of China story that John Bassett III has.

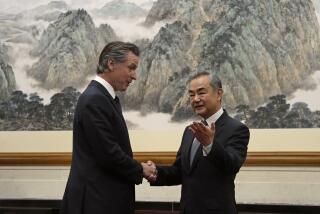

One day in November 2002, Bassett, a third-generation furniture maker from Virginia, found himself in China meeting the Communist party official and businessman intent on putting him out of business.

This official’s ambitions and instructions were clear and direct: His company would soon be the biggest furniture manufacturer in the world, and resistance was futile. Bassett was told he should shut his U.S. factories and contract his production to China. It was the only way his business would survive.

“He was not belligerent, but it was just like you were speaking to a judge,” Bassett recalls for author Beth Macy in her new book, “Factory Man: How One Furniture Maker Battled Offshoring, Stayed Local — And Helped Save an American Town.”

The book, published by Little Brown, recounts Bassett’s struggle to save his business and take on China. “He was absolutely serious and confident in what he was saying,” Bassett said of the official. Bassett’s reaction was to do the very opposite.

Within a year he had mobilized much of the U.S. furniture industry and hired a top lawyer to mount a trade case against Chinese manufacturers for dumping bedroom furniture suites below cost on the U.S. market. And if his furniture business is alive today, it is largely because Bassett won that fight.

We have for some time been awash in books detailing the costs in shut factories and lost jobs that have come with rise of China and the advent of truly international supply chains.

But “Factory Man” deserves to be read for anyone wanting to wrap their heads around the present-day dynamics and politics of globalization. Macy’s book is an important read, whether or not you agree with its premise and economics.

“Factory Man” tells the story of one man’s fight to save a dying industry and the small southern towns that depend on it. There is an element of Don Quixote about it, as some of Bassett’s critics point out.

But it is also about the much bigger theme of U.S. competitiveness and the angst over lost manufacturing jobs that has been at the heart of the debate over trade ever since Bill Clinton signed the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1993.

The figures are stunning. In the two years after China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001 and cheap Chinese-made furniture began flooding the U.S. market, almost a million jobs were lost as American furniture factories were shuttered. Many of them were in the rural Virginia and North Carolina company towns that over the previous century had become the focus of the industry in North America.

In truth, as Macy acknowledges, China did to those Southern towns what the Southern firms had done to Grand Rapids, Mich., just a few decades before, by paying lower wages and shamelessly turning out cheaper copies of popular furniture to grab market share.

The U.S. industry also had its fair share of problems and misplaced arrogance. Among them was a boozy and sexually charged business culture that leads Macy to describe its heyday as “Mad Men in the mountains. With moonshine instead of martinis.”

But the book nevertheless does a good job of showing how some successful U.S. businesses have learned to adapt and compete with China and have started to “reshore” their production.

Bassett relentlessly invests in new machinery for his factories and decides that he will beat his Chinese competitors on quality and service — rather than just price. The answer to China is not just to hire lawyers, the message goes, but to innovate.

It is also clear that there is an element of futility in fighting globalization. After punitive anti-dumping duties are levied by the U.S., the production of bedroom furniture does not come home to Virginia as Bassett hopes — it moves to Vietnam.

And the fight is costly: One economist estimates that the legal battle ends up costing $800,000 per job saved.

Yet Bassett remains a compelling character with a compelling case.

Near the end of the book, his anti-dumping fight won and retirement nearing at age 75, he offers a typically plain-spoken account of why it is important to preserve a U.S. manufacturing industry.

“Everybody thinks all the great ideas come outta MIT, but let me tell you, there’s a great deal of innovation that comes off the factory floor,” he tells the author. “If we close everything, that innovation’s gonna move to wherever the factory is. We gotta invest in America, instead of derivatives.”

That is the sort of argument that plenty of Americans find appealing these days.

Donnan is the world trade editor at the Financial Times of London, in which the review first appeared.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.