At meeting with Boeing staff, pilots fumed about being left in dark on 737 software

Boeing executives sat down in November with pilots at the Allied Pilots Assn.’s low-slung brick headquarters in Fort Worth.

Tensions were running high. One of Boeing’s new jets — hailed by the company as an even more reliable version of Boeing’s stalwart 737 — had crashed into the ocean off Indonesia shortly after takeoff the month before, killing all 189 people aboard the flight, operated by Lion Air.

After the crash, Boeing issued a bulletin disclosing that this line of planes, known as the 737 Max 8, was equipped with new software as part of the plane’s automated functions. Some pilots were furious that they were not told about the new software when the plane was unveiled.

Dennis Tajer, a 737 captain who attended the meeting with Boeing executives, recalled, “They said, ‘Look, we didn’t include it because we have a lot of people flying on this and we didn’t want to inundate you with information.’”

“I’m certain I did say, ‘Well, that’s not acceptable,’” said Tajer, a leader in the association representing American Airlines pilots.

A Boeing spokesman said the company disputes that any of its executives made that statement.

On Wednesday, federal regulators ordered the grounding of the 737 Max 8 and a similar plane, the 737 Max 9, after another crash involving the plane, on this occasion in Ethiopia on Sunday. Many other countries had already acted.

In statements throughout the week, Boeing has said that safety is its top priority. But it also announced that it would take several steps to make the planes “even safer,” including updating the flight control software as well as pilot displays, operating manuals and crew training. The company said these changes would be implemented over the coming weeks.

The announcement comes after years in which Boeing had trumpeted the new plane as offering a “seamless” transition from previous models, a changeover that would not require carriers to invest in extensive retraining.

And it highlights concerns from pilots and other groups about whether Boeing moved fast enough to address potential problems after the Lion Air crash.

Congress, regulators and the company’s shareholders are now scrutinizing the decisions.

On Wednesday, Rep. Peter A. DeFazio (D-Ore.), chairman of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, said he would hold hearings to study the Federal Aviation Administration’s process for approving the planes.

DeFazio cited a concern that has particularly alarmed pilots: the software that was flagged in the bulletin sent after the Lion Air crash.

The software, known as the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System, or MCAS, can in some rare but dangerous situations override pilot control inputs unless it is switched off. This can interfere with pilots’ longtime training that pulling back on the control yoke raises a plane’s nose, putting the plane into a climb. That means that as a pilot tries to maneuver an airplane, the automated system may be counteracting that pilot’s inputs.

“I’m going to investigate how they came to the conclusion that retraining was not necessary, and then obviously we’re going to want to look at how foreign countries certify their pilots and retrain them,” DeFazio said.

After the Ethiopian Airlines crash Sunday, Boeing said it would update flight control software, provide more training, introduce “enhancements” to external sensors that measure the direction of an aircraft and make changes to how MCAS is activated.

But two pilots who attended the meeting with Boeing in November after the Lion Air crash said pilots had suggested that the company take these actions at that time.

“Whatever level of training they decided on [before the Lion Air crash], it resulted in an iPad course that I took for less than an hour,” Tajer, the American Airlines pilot, said. “A lot of pilots here at American did that course.”

But he said the course did not cover the new MCAS. “There was nothing on the MCAS because even American didn’t know about that. It was just about the display scenes and how the engines are a little different,” he said.

Boeing did not comment on the pilots’ concerns.

The same week Boeing executives met with pilots in Fort Worth, they also asked pilots at Southwest Airlines — which also owns 737 Max planes — to meet with them. They hurriedly arranged a conference room at the Reno airport the Sunday after Thanksgiving, said Jon Weaks, president of the Southwest Airlines Pilots Assn.

“At that meeting, they told us that a software update would probably be forthcoming in the near future,” Weaks said.

But no update came in the following two months.

Boeing did not comment on the meeting. In a statement earlier this week, Boeing said it had been working on the software enhancements for the 737 Max for the last several months in the aftermath of the crash of Lion Air Flight 610.

The company said it had been working closely with the FAA on the software update and had also been soliciting feedback from airlines that operate the plane.

The concerns in meetings with Boeing executives were not the only signs that pilots were worried about the airplane. A federal flight safety reporting system contains about a dozen reports by pilots expressing exasperation about systems that limited their control of the 737 Max.

Nearly two-thirds of the complaints were mainly flagging perceived faults with the aircraft or shortcomings and ambiguities in instruction, according to an analysis of the Aviation Safety Reporting System by the Washington Post. The Dallas Morning News first reported on the pilots’ complaints.

“I think it is unconscionable that a manufacturer, the FAA, and the airlines would have pilots flying an airplane without adequately training, or even providing available resources and sufficient documentation to understand the highly complex systems that differentiate this aircraft from prior models,” one pilot wrote in November. “The fact that this airplane requires such jury rigging to fly is a red flag. Now we know the systems employed are error prone — even if the pilots aren’t sure what those systems are, what redundancies are in place, and failure modes.”

Pilots expressed confusion about various features of the airplane.

“I reviewed in my mind our automation setup and flight profile but can’t think of any reason the aircraft would pitch nose down so aggressively,” one pilot wrote.

“How can a captain not know what switch is meant during a preflight setup?” asked another. “Poor training and even poorer documentation; that is how.”

The FAA pushed back against the idea that these pilot complaints could have assisted in identifying problems, saying they did not involve the MCAS that has been at the heart of pilots’ concerns.

“Some of the reports reference possible issues with the autopilot/autothrottle, which is a separate system from MCAS, and/or acknowledge the problems could have been due to pilot error,” it said in a statement.

Boeing declined to comment on the system. Southwest, which uses the 737 Max planes, said it had received no reports of issues with the MCAS. American Airlines said it reviewed data for more than 14,000 flights since the Lion Air crash in Indonesia and has “not seen a single anomaly related to the MCAS.”

In its order grounding the planes Wednesday, the FAA said it had received information from the Ethiopian Airlines wreckage “concerning the aircraft’s configuration just after takeoff that, taken together with newly refined data from satellite-based tracking of the aircraft’s flight path, indicates some similarities” between what happened with that flight and the Lion Air flight in Indonesia.

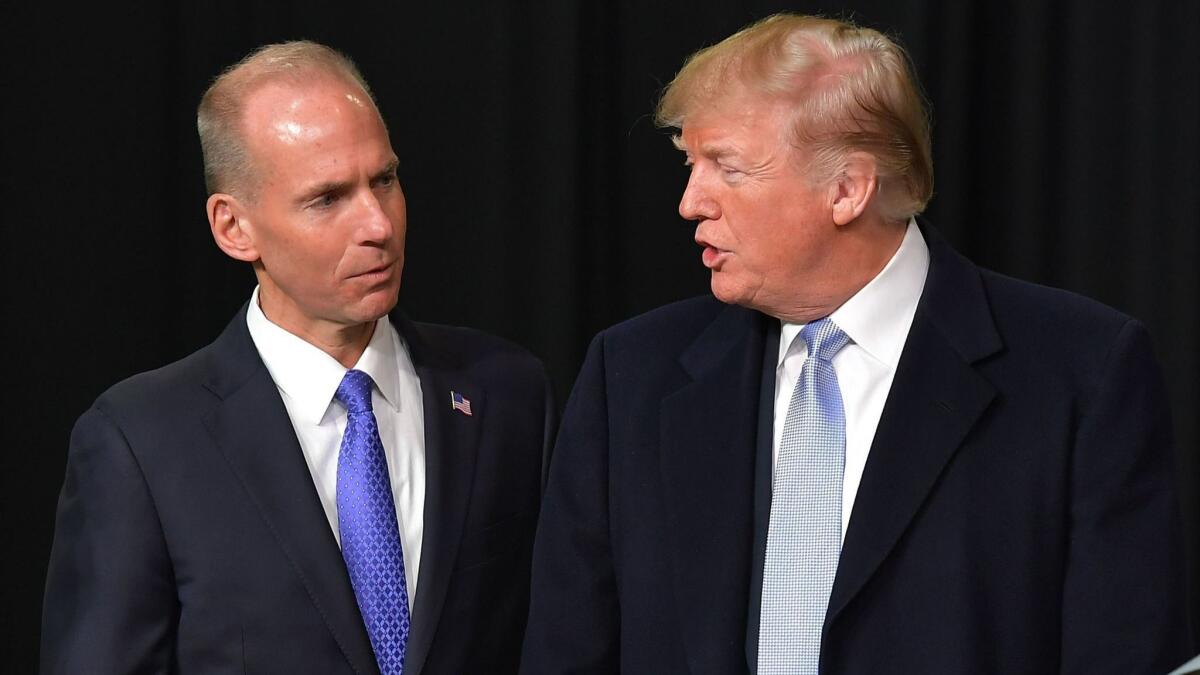

Boeing is scrambling to maintain its reputation for making safe and profitable airplanes. Chief Executive Dennis A. Muilenburg called President Trump on Tuesday, the White House said, to vouch for the safety of the planes.

On Wednesday, the company issued a statement saying that “out of an abundance of caution and to reassure the flying public of the aircraft’s safety,” it agreed with the FAA’s decision to ground the planes.

“Boeing continues to have full confidence in the safety of the 737 MAX,” the company said.

Boeing designed the 737 Max to fly up to 3,850 miles, and it became a key tool in the company’s global ambitions.

The Max uses engines that are both bigger and more fuel-efficient, and the new engines have been moved slightly forward on the wings compared with previous models. To compensate for the repositioning, Boeing added MCAS to replicate the handling characteristics of earlier models.

In the Lion Air crash, according to a preliminary report, the 737 Max seemed to careen up and down repeatedly. Analysts said this suggested the MCAS was redirecting the plane whenever it went into a nose-up position by pointing the nose down.

In an appearance on CNBC in December, Muilenburg was asked whether the company was doing enough to ensure pilots were properly trained after the October crash.

Muilenburg said that the company’s bulletin on the software helped in “directing pilots and airlines to these existing procedures” and that Boeing was “taking a look at that to make sure all the appropriate training is in place and that the communications with our customers are there.”

“It’s very, very important to us, but I will say bottom line here, very important, is that the Max 737 is safe,” he said.

Muilenburg’s comments came about a week after the meetings in Texas and Reno, when pilots said they heard similar promises.

Sitting around pullout tables in leather-backed chairs, Tajer said, some of the company’s top engineers were apologetic.

“We said, ‘Shame on you.’ They said, ‘I know.’ ”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.