Remember when Amazon only sold books?

When

“That’s actually a very liberating expectation, expecting to fail,” he said to Time magazine when it named him Person of the Year in 2000.

By then, sales had ticked past $1 billion, but the company had yet to turn a profit. Some analysts remained skeptical that Bezos could deliver on his plan to sell everything and anything. (“Anything with a capital A,” he told Time.)

But two decades after its launch, Amazon has conquered online retail, racking up $136 billion in sales in 2016. It’s also taken on cloud computing, tech gadgets and the entertainment world. With its blockbuster announcement Friday that it is buying upscale grocery chain

As consumers increasing rely on the Seattle-based e-commerce giant, it’s hard to remember a time when Amazon sold only one product: books.

“There's virtually nothing left that they haven't touched,” said Kelly O’Keefe, professor at the Virginia Commonwealth University Brandcenter.

Books

Amazon.com launched its online bookselling site at a time when bookstore chains such as Barnes & Noble, Waldenbooks and Crown Books were familiar storefronts in American shopping malls.

Promoting itself as “Earth’s Biggest Bookstore,” Amazon opened for business in July 1995, using major book distributors and wholesalers to rapidly fill its orders. “The idea of selling books online was a foreign one, it took a while to take off,” O’Keefe said.

But not long. Not beholden to the physical constraints of a brick-and-mortar shop, Amazon was carrying more than 2.5 million titles by 1997, and its sales totaled $148 million that year. The company had 1.5 million customers in more than 150 countries.

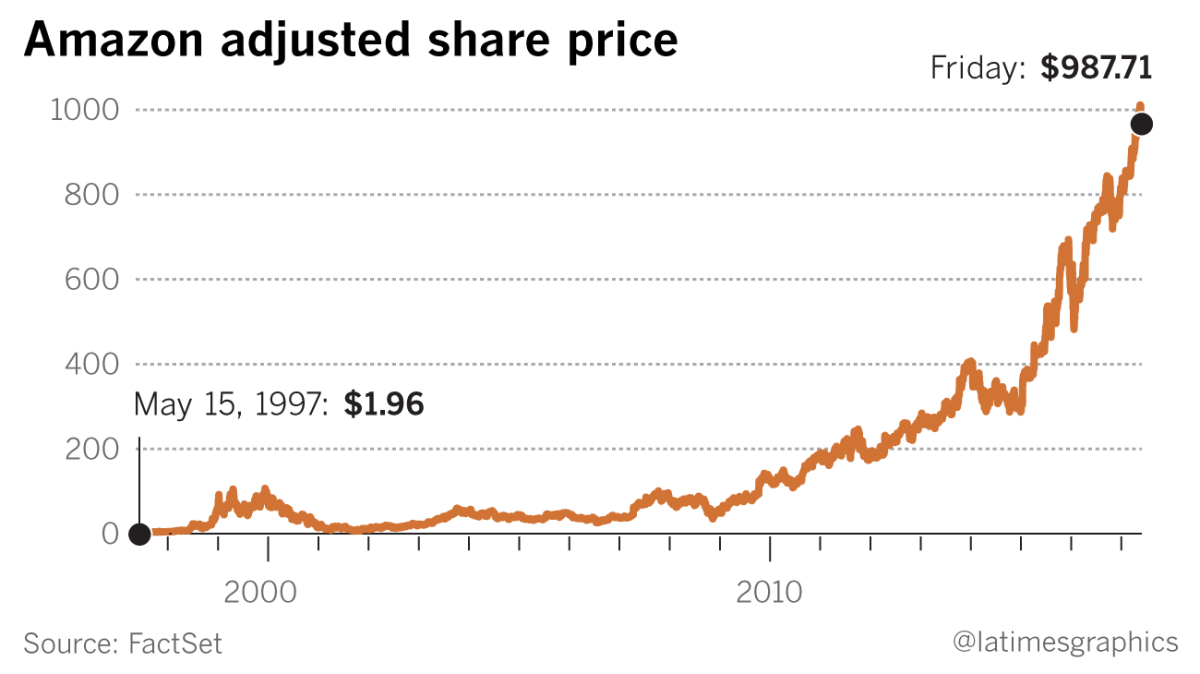

The company went public on May 15, 1997 with its stock priced at $18 a share and a market capitalization of roughly $438 million.

The stock closed Friday at $987.71, giving Amazon a total market value of $475 billion.

The Everything Store

Amazon’s success with books allowed the e-commerce behemoth to expand far beyond its origins.

Selling electronics helped the company grow rapidly and put traditional electronics stores like Circuit City out of business. It’s also possible that consumers learned new ways to price-shop; they “unintentionally were able to leverage brick-and-mortar stores as showrooms for their own products,” O’Keefe said.

From computers and home goods to sex toys and shoes, there’s not much that Amazon doesn’t offer shoppers these days.

Amazon Web services

In the early 2000s, Amazon realized it had been sitting on a technology gold mine. The computer systems that powered its online shop were so robust that Amazon figured it could expand its network and be the backbone of many more online stores.

The idea of a company trusting a third party to store its proprietary data didn’t take off overnight. But Amazon can thank Apple’s

The company is setting itself up to be a major foundation — though with unproven financial returns — for the next generation of technology by allowing software developers to build upon Alexa and machine learning, or automated computing, tools.

The computing infrastructure also has helped Amazon quickly launch an advertising technology business that helps other shops identify potential customers based on their interests. With just over $1 billion in ad sales, Amazon isn't making a big dent in the businesses of industry leaders Google and Facebook. But advertising experts say Amazon has the data and software expertise to catch up fast.

Hardware

The company gave the world a glimpse of its enormous ambition when it starting making its own tech devices.

It launched the popular Kindle e-reader in 2007, a product that has gone on to be a category leader. Morgan Stanley estimates that the company sold $5 billion in Kindle devices in 2014.

It also got in on the tablet market with the Amazon Fire HD in 2012, and the video and audio streaming marketing in 2014 with the Amazon Fire TV — both with moderate success.

Its 2014 Fire Phone — meant to compete with the iPhone and Android phones — was a total flop, though, and the company took a $170-million hit. It discontinued the phone a year later.

Instead of being burned by its smartphone venture, the company launched its digital home assistant device, the Amazon Echo, in 2015. The company was the first to release such a device, which doubled as a home speaker and came packaged with Alexa, the voice-commanded artificial intelligence that can answer questions, make orders on Amazon and play music.

While the Echo was initially slow to gain traction, the launch of similar devices from Google and Apple introduced more customers to the relatively new product category.

Analysts describe voice-enabled assistants as the next frontier, and the Echo as the front-runner. Patrick Moorhead, a principal analyst at Moor Insights and Strategy, once described the Echo as a “Trojan horse."

“You bought it to do a few simple things and be a speaker, then they get you comfortable and send you weekly updates to let you know what you can do with it and ultimately once you go out and get those smart lights or smart door locks, you will be comfortable telling it to do things,” Moorhead said.

Entertainment

When Amazon Studios launched in 2010, few in Hollywood knew what to make of the nascent production company’s ambitions. The fledgling division solicited online script submissions, receiving thousands of screenplays for feature films and television pilots but developing few of them.

Run by former Walt Disney Co. executive Roy Price, Amazon’s foray into original programming started modestly, with series including the

Then in 2017, Amazon made history by becoming the first streaming company to score an Oscar nomination for best picture, with the Casey Affleck drama “Manchester by the Sea.” Amazon paid an eye-popping $10 million for the domestic rights to the film at the 2016 Sundance Film Festival.

“To imagine two or three years ago that Amazon would have a film in Oscar contention would’ve been almost unthinkable,” Paul Dergarabedian, senior media analyst at comScore, said at the time.

AmazonStudios, nominated for seven Academy Awards, ultimately took home three wins — with “Manchester by the Sea” being recognized for best original screenplay and best actor and “The Salesman” getting the nod for best foreign film.

Amazon’s lineup of upcoming films includes the

The company’s media division has also grown through acquisitions. Buying Twitch gave Amazon a video rival to YouTube best known for live streams of video-game matches. Amazon Prime subscribers get access to special features on Twitch, which has seen an uptick in productions from other genres. That includes cooking shows, marathons of TV shows such as “Mister Rogers” and live sewing demonstrations.

Amazon also purchased a video-game studio that’s begun releasing a slate of games, including the team brawler “Breakaway.” And for a brief time through Twitch, it owned an e-sports team.

More recently, job postings show Amazon is looking for news editors to produce digests of trending topics that likely would be fed into Alexa, the virtual assistant found on Echo speakers.

Last year, the company also launched a music-streaming subscription, Amazon Music Unlimited, to compete with Pandora and Spotify.

Groceries

Amazon has long had aspirations as a grocer, starting in 1999 when it invested millions in HomeGrocer.com, a first-of-its-kind online supermarket that was ultimately doomed by the dot-com bust.

It wasn’t until 2007 that the company launched its first grocery delivery service, AmazonFresh, rolling it out slowly by invitation-only to residents of the affluent Seattle suburb of Mercer Island. Pick-up locations were later added in nearby Kirkland and Bellevue.

In 2013, AmazonFresh expanded to Los Angeles and San Francisco. More cities have been added, including San Diego, New York and Philadelphia as well as Tokyo and London.

The service was initially met with skepticism given the difficulty getting perishables to customers on time — particularly in cities such as L.A. known for traffic gridlock. And for all the convenience AmazonFresh provides, it often remains pricier than your neighborhood market. Subscribers must be Amazon Prime members, which costs $99 a year. AmazonFresh is an additional monthly membership for $14.99.

The $13.7-billion Whole Foods deal marks Amazon’s biggest foray into groceries.

“The final was always food,” O'Keefe said. “It's a smart deal for continuing the sales of online groceries and it is likely that we'll see them grow rapidly.”

What's next for Amazon?

Amazon’s deal-making team, led by senior vice president for business development Jeffrey Blackburn, doesn’t appear to be slowing down. Amazon has showed interest in acquiring workplace chat app Slack in a deal that could value the start-up at $9 billion, Bloomberg reported last week.

Another possible next venture for Amazon is same-day delivery services like GrubHub or Postmates, some analysts say.

“The next logical move is … strategic partnerships that allow Amazon to streamline the consumer experience from delivery to in-store shopping experience,” said Tom Ball, co-founder and managing director of Next Coast Ventures. “Let the multibillion-dollar grocery market games begin."

For some, Amazon's acquisitions signal lower costs for all the products consumers use on a daily basis. But Lloyd Greif, president and CEO of Greif & Co., warns that once Amazon has complete control, it will be free to raise prices dramatically as it sees fit.

“Amazon is an octopus and it has its tentacles everywhere,” Greif said. “Once it's completed its mission, then you're going to have the price inflexibility that's not in the consumers’ interest.”

Ryan Faughnder, Tracey Lien and James Peltz contributed to this report.

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.