Even after a brutal hurricane season, airlines are doing just fine

Only days after monster storm Irma made landfall in Florida, canceling and delaying thousands of flights, the head of the world’s largest airline appeared unfazed, voicing glowing optimism about the future of air carriers.

Speaking at an industry conference in Washington, D.C., Doug Parker, the chief executive of

“I don’t anticipate a financial impact to us other than the near-term financial impact,” he said. “I feel as good about this business as I ever have.

How could that be in a time when monster storms are more common — and some fear that travel disruptions could become a regular occurrence amid quickening climate change?

Chalk it up to science, technology and profits.

The nation’s $1.5 trillion airline industry is in the midst of one of its most financially stable eras in decades, which will help the biggest carriers absorb the short-term impacts of the unusually destructive hurricane season. Increasing passenger demand and cheap fuel costs have been key in helping build the carrier’s profit margins and cash reserves.

But advances in science and technology are also playing a role. Modern weather forecasting has improved to the point that airlines can now tell with high reliability the moment a storm is expected to reach a major airline hub, making it easier to cancel and reschedule flights.

“It has helped them to be prepared, move equipment out of harm's way and recover faster than in past decades,” said Helane Becker, an airline analyst for Cowen & Co.

Although it is too early to estimate the final dollar cost of the two hurricanes, the nation’s bigger airlines seem prepared to overcome the financial blow despite the storms’ enormous impact.

Between the end of August and the first week of September, Hurricane Harvey pounded south Texas, prompting the cancellation of 11,300 flights to and from airports in Houston, according to the flight-tracking website Flightaware.com.

United Airlines, the biggest carrier at George Bush Intercontinental Airport, and

About a week later, Hurricane Irma began to tear through Florida and the Caribbean, forcing the closure of 40 airports and the cancellation of 14,500 flights in and out of the state and the nearby islands.

As the biggest airline at Miami International Airport, American Airlines had to cancel more than 5,000 flights. As the storm moved inland, another 1,100 flights were canceled from Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport, the world’s busiest airport.

The canceled flights represented a fraction — less than two-tenths of 1% — of the more than 16 million flights that take off every year in the U.S.

Still, the financial impact of the storms would, in previous times, have put a big dent in the profit margins of most airlines, said Seth Kaplan, managing partner at Airline Weekly, a trade publication.

“At a different moment in history, this kind of impact could have made the difference between profits and losses,” he said.

Instead, airline executives have been downplaying the impact on themselves and passengers.

The airlines are expected to lose money on some canceled airfares but not all of them. On all canceled flights, passengers received full refunds and most of the airlines agreed to waive change fees for those passengers whose flights were not canceled but decided to stay clear of the storm.

“There’s a blow, and we are going to absorb it,” Gary Kelly, chief executive of Southwest Airlines, said at the Sept. 13 aviation conference. “We’ll still be healthy. We’ll take care of our people, and we’ll take care of our customers.”

American Airlines issued a report, two days after Hurricane Irma made land in Florida, saying that instead of a pre-tax profit margin of 10% to 12%, the carrier was now expecting a slightly smaller margin of 8.5% to 10.5% for the July-to-September quarter.

During the storms, weather forecasts were able to monitor the speed and direction of the hurricanes to give airlines a good idea when to begin canceling flights and where to dispatch the planes and crews to ride out the storm.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration now deploys a network of radar systems that scan the skies, satellites that take images from space, buoys on the sea to measure water temperatures and wave heights, and scores of weather balloons — all sending data into super computers that conduct atmospheric modeling to predict the size, speed and direction of storms and hurricanes.

That data allow carriers to avoid having planes loaded with passengers stuck at a storm-ravaged airport. During the recent storms, the carriers were able to cancel flights sooner and dispatch their multimillion-dollar planes to airports where they could avoid wind damage or undergo needed maintenance.

More accurate forecasts also made it easier for airlines to know when to relaunch flights after the winds subsided.

The changing nature of travel booking also has made it easier for air travelers to reschedule in the event of a weather disaster.

Not only has online travel booking outgrown booking through a travel agent, but more than half of all online reservations are made using mobile devices instead of a desktop or laptop computer. This means travelers can literally book and reschedule travel plans on the go.

Leisure travelers who were prevented by the hurricanes from flying to tourist destinations such as Walt Disney World in Orlando or the Florida Keys either postponed their trips or made plans to fly to other vacation spots, industry experts said.

The biggest financial hit to the airlines will be the loss of those airfares booked by business travelers, who tend to buy more expensive first-class seats but are less likely to reschedule a canceled business trip.

But today’s airlines can absorb a more severe financial blow because they are bigger and more efficient.

Fort Worth-based American Airlines became the world’s largest carrier by merging with one of its rivals

It was one of several mergers and acquisitions in the airline industry over the past decade, prompted by the financial double-hit of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist strikes and the ensuing recession. From 2001 to 2009, the nation’s biggest airlines lost a combined $65 billion, with more than a dozen major carriers filing for bankruptcy or ceasing operations.

The industry emerged stronger, though, with four mega airlines — American, United, Delta and Southwest — now controlling more than 80% of all domestic flights.

“They’ve got an oligopoly now, and they are dictating everything,” said Richard Gritta, a professor of finance at the University of Portland's Pamplin School of Business.

Other trends have further strengthened the financial footing of the enlarged airlines.

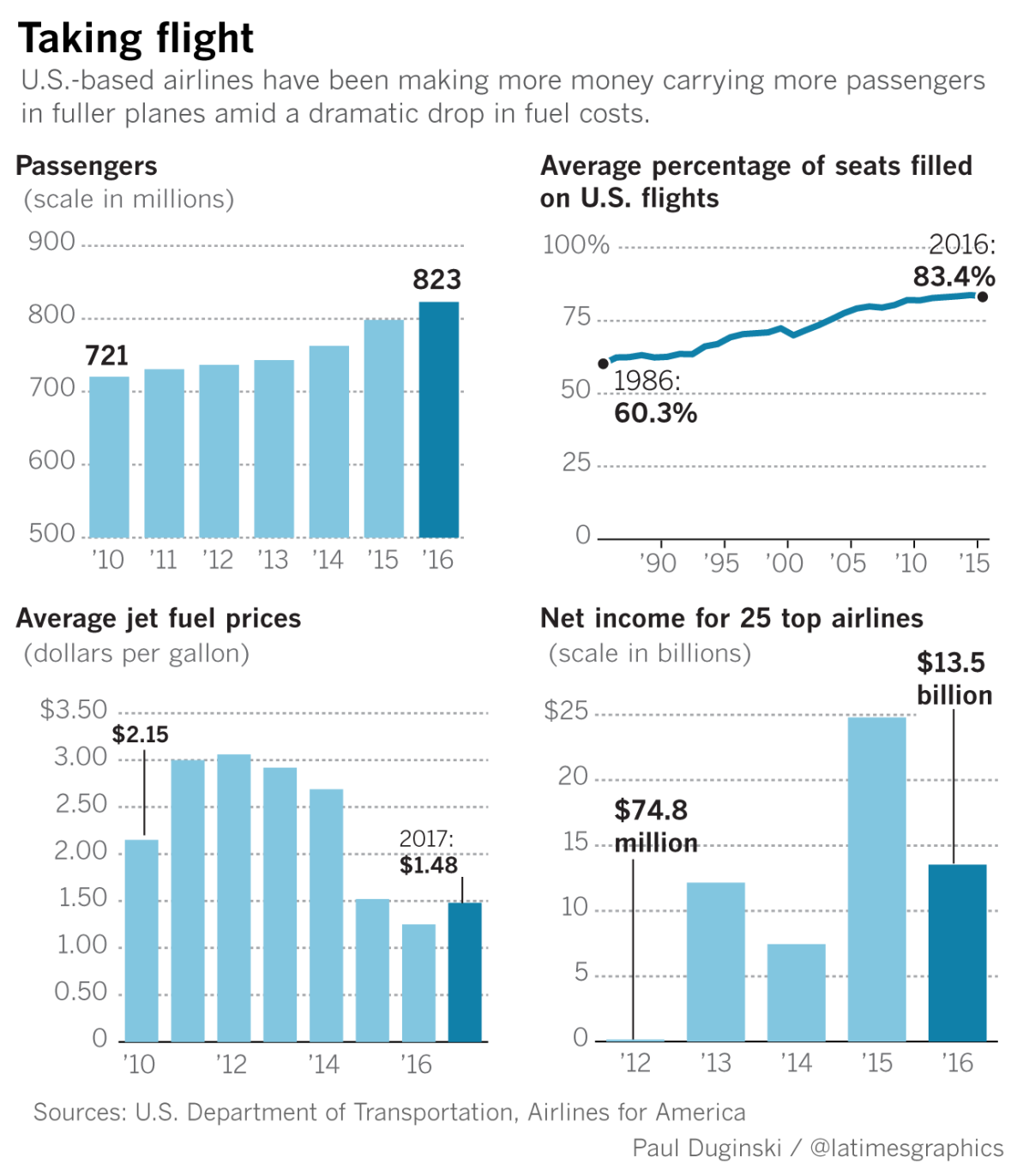

Since 2013, fuel prices — one of the biggest industry expenses — have dropped by about 50% while demand for air travel has been growing by more than 4% per year.

Earlier this month, the Department of Transportation reported that U.S.-based airlines carried an all-time high number of passengers during the first six months of 2017 — 414 million, up nearly 3% from the previous record for a six-month period set in 2016.

And U.S.-based airlines are now operating more efficiently by packing those passengers into smaller seats on larger planes.

The results have been record profits for nearly every major carrier. From 2010 to 2016, the country’s biggest airlines earned a combined $61.7 billion in profits.

“The airlines are certainly well-capitalized and can handle these disruptions,” Becker said.

Airlines have become so profitable that famed investor

The Omaha-based financial whiz invested nearly $10 billion through his holding company

Buffett says he’s changed his tune because he believes airlines have learned to operate with discipline, no longer adding more capacity — by buying planes and launching new routes — than is justified by demand.

“It’s true that the airlines had a bad 20th century,” Buffett said in an interview on CNBC. “They're like the Chicago Cubs. And they got that bad century out of the way, I hope.”

Of course, the airlines’ profit-making tactics have prompted a backlash from air travelers.

Nearly every major carrier has installed coach seats with less legroom and width, allowing airlines to cram nine to 12 more seats per plane. The seats are even thinner and have less cushioning.

Airline passengers — already frustrated by a growing menu of fees charged by airlines for onboard food, drinks and other extras — have erupted in feuds with their fellow fliers over the shrinking personal space. In 2014, at least three flights were diverted to quell passenger squabbles.

Passenger rights group, Flyersrights.org, filed a request with the

The organization argued that the average seat pitch — the distance between the back of one seat and the back of the next — has shrunk from an average of 35 inches to 31 inches, while the width has shrunk from 18.5 inches to 17 inches in the last decade or so.

But whatever final loss the airline industry suffers from the storm, industry experts say the carriers are not likely to raise airfares to make up for the financial blow.

“Airlines always do the same thing,” Kaplan said. “They charge only as much as people are willing to pay.”

To read more about the travel and tourism industries, follow @hugomartin on Twitter.

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.