Weinstein Co., the once prominent indie studio, filed for bankruptcy with only $500,000 in cash

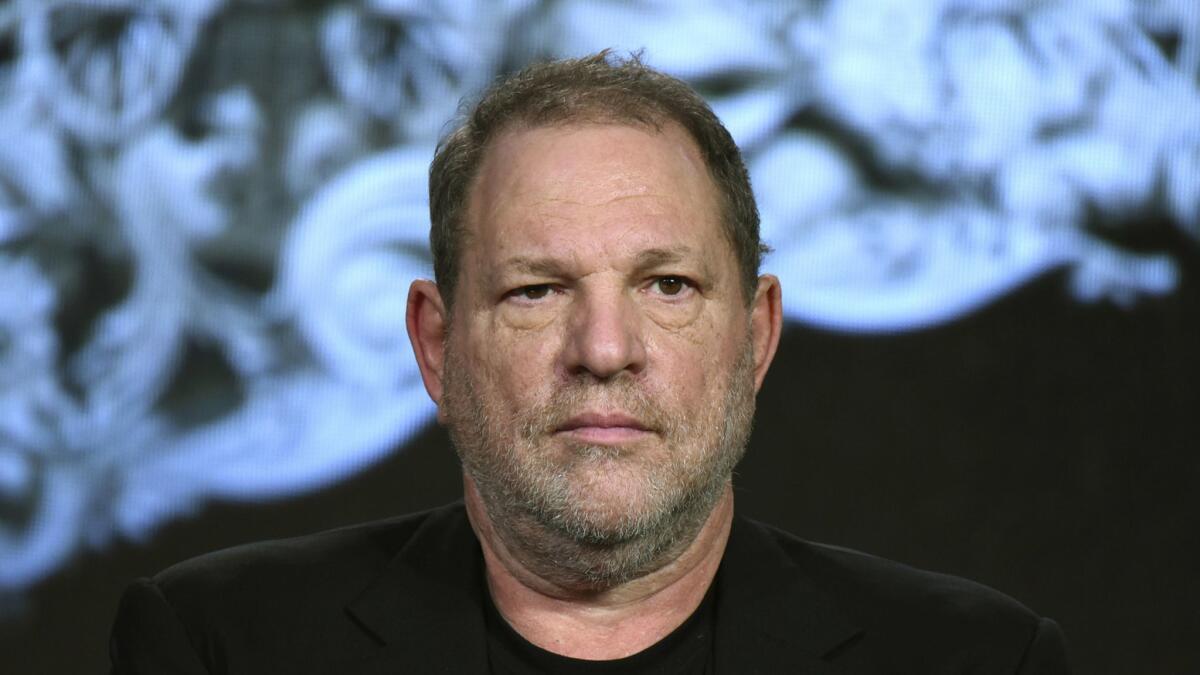

Weinstein Co.’s Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing had long been viewed in financial circles as the inevitable result of the sexual abuse allegations against its namesake founder. Even so, the bankruptcy documents, filed late Monday night, paint a bleak picture of a once-formidable entertainment company that had nearly run out of funds after a desperate search for a buyer.

More than five months after dozens of women accused Harvey Weinstein of sexual harassment and assault, the studio known for “The King’s Speech” and “Django Unchained” had less than $500,000 in cash before seeking Chapter 11 protection from creditors, according to federal court documents.

The filing reveals that the company owed more than $500 million to a list of creditors spanning 394 pages.

The financial strain illustrates the catastrophic impact of the allegations and ensuing lawsuits against Harvey Weinstein on the New York company and its employees. Since the first allegations surfaced in October after an expose by the New York Times, the company’s workforce shrank to just 85 full-time employees from 120.

MORE: Fate of Harvey Weinstein sexual assault cases now in hands of two cautious prosecutors »

As Weinstein Co.’s standing in Hollywood deteriorated, companies such as Amazon, Apple and Hachette Book Group cut ties and canceled projects. Quentin Tarantino, long a prized filmmaker for Weinstein, jumped to another studio for his next movie.

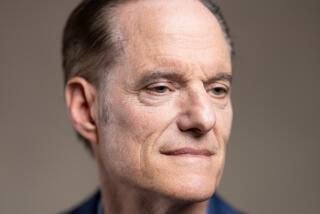

The allegations left the company unable to function, Robert Del Genio, the chief restructuring officer for Weinstein Co. overseeing the bankruptcy process, wrote in his declaration.

“Even longstanding business partners have refused to return the company’s phone calls,” said Del Genio, a senior managing director for corporate finance and restructuring at Washington, D.C.-based FTI Consulting.

To remain in business, the studio sold off major films including “Paddington 2” and “Six Billion Dollar Man.” The company collected $13 million by selling the rights to the “Paddington” sequel to Warner Bros., which also bought “Six Billion Dollar Man” for $7.2 million. Weinstein Co. also sold the Robert De Niro comedy “War With Grandpa” to its producers for $2.5 million.

“They were selling film rights and film properties left and right,” said Jack Tracy, a legal analyst with Debtwire, a firm that provides information about bankruptcy cases. “Despite all those efforts, they only had $500,000 in cash.”

Weinstein Co.’s lengthy lineup of creditors includes the expected cadre of banks, production companies, attorneys and vendors. But the list also contains some surprises among the names, including the late David Bowie, Malia Obama (the former president’s daughter who interned for the company) and the right-wing outlet Breitbart News. New Zealand-born model Zoe Brock, who is part of a class-action lawsuit against Weinstein Co., also appears on the list.

Despite its cash woes, court documents paint a picture of a studio spending on luxury items. Its creditors include a limo service, a ski tour company in Aspen, Colo., and a Porsche dealership in Beverly Hills.

Secured creditors including Union Bank and billionaire Len Blavatnik’s Access Industries, who are first in line to be paid in a bankruptcy sale, are owed a total of about $345 million, according to court filings. That includes $156.4 million owed to Union Bank under a senior credit facility, $18.1 million owed to Bank of America under a term loan agreement, and $45.5 million in obligations to Access Industries.

The bankruptcy petition lists 30 top unsecured creditors — including law firms, production companies, studios and other vendors — who have claims totaling at least $100 million.

Among the largest unsecured creditors is Wanda Pictures, the film subsidiary of a Chinese real estate and entertainment conglomerate that has invested in Weinstein movies. Wanda is owed $14.4 million. Law firm Boies, Schiller & Flexner, which has represented the company and its founders in numerous matters, is owed more than $10 million.

Major unsecured creditors also include Viacom, Technicolor, Disney and Sony Pictures. The document lists law firm Leto Bassuk as the largest unsecured creditor, seeking payment of a disputed $17.4-million judgment.

The bankruptcy filing is merely the first step in Weinstein Co.’s effort to rise from the ashes after previous attempts to sell assets failed.

Weinstein’s filing comes just weeks after the sudden collapse of an agreement to sell the company to billionaire Ron Burkle and former Small Business Administration head Maria Contreras-Sweet for $500 million. People close to the Burkle deal said they walked away from the agreement in early March because they found more than $50 million in undisclosed liabilities on the company’s books.

On Monday, Weinstein Co.’s board of directors said it had secured a “stalking horse” bid from Dallas private equity firm Lantern Capital Partners that sets a floor for an auction for the assets.

Lantern, which was a minority backer of the failed bid by Burkle and Contreras-Sweet, has offered $310 million in cash for the company. Under the deal terms, Lantern would also assume $115 million in liabilities related to TV shows — tied to franchises such as “Scream,” “Spy Kids” and “The Mist” — and individual movies, including “The Upside,” “The Current War” and “Polaroid.”

Competing bids for the assets are due April 30. Companies such as Lionsgate and Miramax parent company BeIN Media have expressed interest in the assets and are expected to bid on them in Bankruptcy Court. Any sale must be approved by the bankruptcy judge.

To stay in business during bankruptcy, Weinstein Co. is counting on $25 million in new financing from Union Bank.

Weinstein Co.’s board said the Lantern bid was attractive because it promised to hire most of the company’s employees and keep the studio going.

Most of the bidders that previously expressed interest were looking for individual assets, including the TV division and individual films, not the whole company, according to people familiar with the process. A group of outsiders could cobble together a bid for the various assets that exceeds Lantern’s offer.

However, Debtwire’s Tracy said, the court is more likely to favor a deal that hands the bulk of the assets to one buyer, making for a simpler process with fewer pitfalls.

“For someone to really compete in this, either Lantern has to step away or someone else has to come to the table with a better price for the whole enchilada,” Tracy said.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.