Column: While you watched Comey, Senate GOP moved to cripple healthcare (and California moved to expand it)

Having learned from their colleagues in the House that the best way — possibly the only way — to pass a grossly unpopular healthcare repeal bill is to hide the details, the Senate GOP used the cover of the Comey hearing Thursday to move the repeal along.

While the eyes of political wonks across Washington, D.C., and the nation were glued to telecasts of former FBI Director James Comey’s testimony about his closed-door encounters with President Trump, Senate Republicans worked to fast-track their version of the American Health Care Act, the measure to repeal the Affordable Care Act that was passed by the House GOP on May 4.

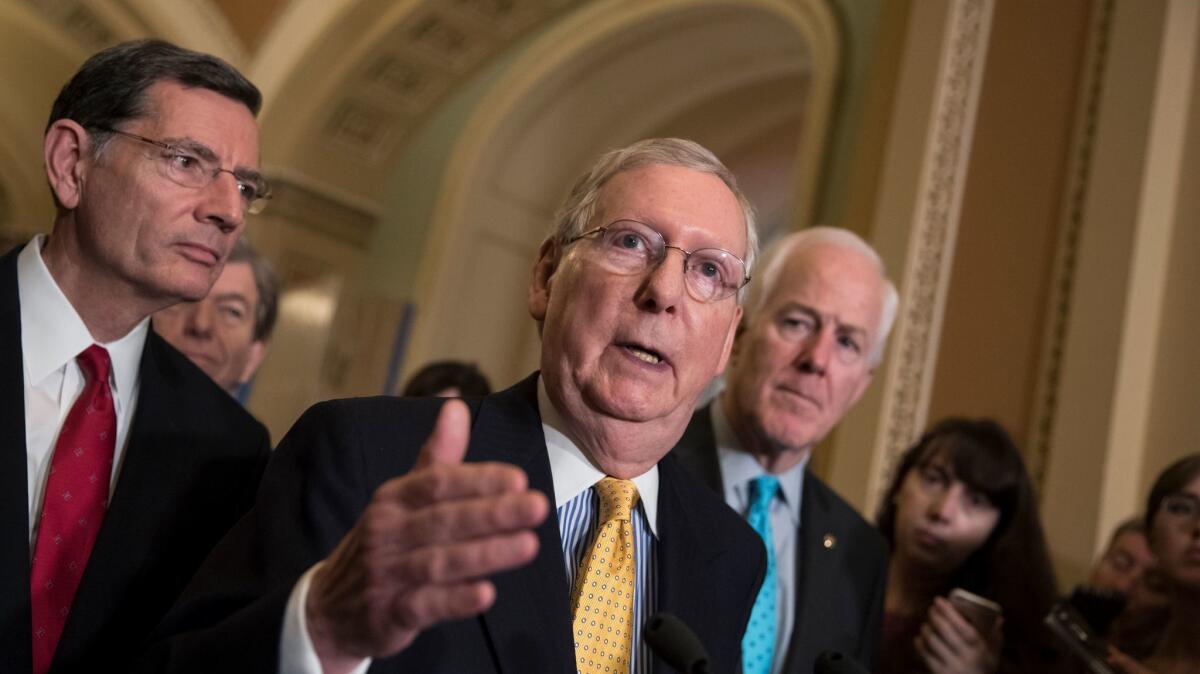

On Wednesday, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., invoked Senate Rule 14, which allows a bill to bypass committee consideration and be brought to the floor for a vote. That means no hearings and no debate, and improves the prospect of a vote before the Senate leaves Washington for its August recess.

We’re not even going to have a hearing on a bill that impacts one-sixth of our economy.

— Sen. Claire McCaskill, D-Mo.

As it happens, the Senate’s work on a measure to cut back the health coverage gains secured by the ACA took place as California budget negotiators reached agreement on restoring dental and optical coverage cut from the state’s Medicaid program, known as Medi-Cal, in 2009. The plan is to restore dental coverage for Medicaid patients in 2018 and eyeglasses in 2020. Some details are still being negotiated, but this is what political leaders do when they’re serious about improving the health of their constituents.

McConnell’s goal is to present a bill to the Congressional Budget Office for analysis as soon as next week, so a final vote can be held before Sept. 30. That’s the deadline for a measure to be passed this year under Senate budget reconciliation rules, which would prevent a Democratic filibuster and allow passage by the GOP’s razor-thin 52-48 majority — with Vice President Mike Pence casting the deciding vote if two Republican senators bail out and produce a tie. (Amanda Michelle Gomez of Think Progress has a good rundown of the procedural complexities here.) Unlike the House, the Senate can’t vote on a bill that hasn’t first been scored by the CBO.

The Senate’s 13-member, all-male healthcare working group labored on the repeal measure Thursday while the Comey hearing was taking place. They might have pulled off the attempt at secrecy had not Sen. Claire McCaskill, D-Mo., raised hell about the process at a meeting of the Senate Finance Committee.

“Will we have a hearing on the healthcare proposal?” she asked committee Chairman Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, a member of the working group. A befuddled Hatch replied, “We’ve invited you to participate and give your ideas.”

“For what?” McCaskill shot back. “We have no idea what’s being proposed. There’s a group of guys in a back room somewhere that are making these decisions… We’re not even going to have a hearing on a bill that impacts one-sixth of our economy…. It is all being done with an eye to try to get it by with 50 votes and the vice president.”

Republicans often point to the all-Democratic vote to enact the ACA in 2010. But what often goes unmentioned is that that bill was subjected to multiple public hearings and amendments — as McCaskill observed, amendments proposed by Hatch and other Republican lawmakers made it into the bill.

Despite the procedural shroud, a few details have leaked out about what the GOP working group is considering. Its goal is to soften some of the more egregious elements of the House GOP’s American Health Care Act without losing the support of right-wingers such as Ted Cruz, R-Texas, and Mike Lee, R-Utah.

They’re walking a tightrope because the House bill, which the CBO says would cost 23 million Americans their health coverage, is hopelessly unpopular. A Quinnipac University poll released Thursday found that American voters disapprove of the measure by 62%-17%. Its unpopularity has only deepened over time; the disapproval split was 57%-20% on May 25. Even among Republicans the measure can’t muster more than a plurality in favor, with approval-disapproval at 42-25. “Every other listed party, gender, education, age or racial group disapproves by wide margins,” the pollsters say.

One provision under consideration by the Senate group is to protect people with pre-existing conditions from insurance rejections or rate hikes, though the mechanism of that guarantee is unclear. The House bill allows states to obtain waivers allowing insurers to reject applicants with medical conditions or surcharge them heavily under certain circumstances.

According to reports from Jonathan Cohn of Huffington Post and others, the working group is toying with slowing down the AHCA’s effective repeal of the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion. Under the AHCA, the federal share of Medicaid expansion, which will never fall below 90%, would be reduced to traditional Medicaid’s rate, which averages 57%, starting in 2020.

Existing enrollees would be funded at the old rate until they leave the program, and new enrollees would be subject to the lower rate. The CBO concluded that states would lose most of the expansion dollars within two years. The provision would triple the annual state cost of maintaining expansion in the 31 expansion states and the District of Columbia to a total of more than $30 billion a year, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. That’s unsustainable for any state budget, which means the effective death of the program.

The Senate’s idea is to stretch out that transition to seven years to give states and their Medicaid enrollees more breathing room. The idea is to settle the stomachs of Republican senators from 10 expansion states with Republican statehouses. But the CBPP calculates that the effect on Medicaid expansion enrollment and state costs would be identical, even with the delay—by 2027, only 100,000 of the 11.1 million Americans currently enrolled in expanded Medicaid would still be on the program.

Who would gain? The savings from cutting expansion, along with the AHCA’s provision converting traditional Medicaid to a skimpy per-capita or block-grant formula, “would help pay for the AHCA’s large tax cuts for people with very high incomes, drug companies, insurance companies, and other industries,” the CBPP says.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email [email protected].

Return to Michael Hiltzik’s blog.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.