Column: Remembering Si Ramo, America’s pioneering renaissance man

The obituaries are all in, chronicling the amazing career of Simon Ramo, who died June 28 at the age of 103. But Ramo was one of those extraordinary individuals whose life can’t be confined, or defined, within columns of newsprint or the pixels on a screen.

I can’t do any better than the thorough obit written by my colleagues Peter Pae and W.J. Hennigan in outlining the milestones of Ramo’s career. I can, however, contribute a few personal observations, drawn from the regular lunches I spent with Ramo over the last few years.

Starting in mid-2010, when I first visited him to gather material for a profile, Si would invite me to see him every six or eight weeks. We usually met at the Los Angeles Country Club; it was a rare lunchtime that we weren’t interrupted by a well-wisher or former associate. Sometimes I would arrive with a question or agenda of my own, related to a column I was planning or a book project. It rarely mattered, because Ramo always had an agenda of his own, and his thoughts were invariably more interesting and illuminating than mine.

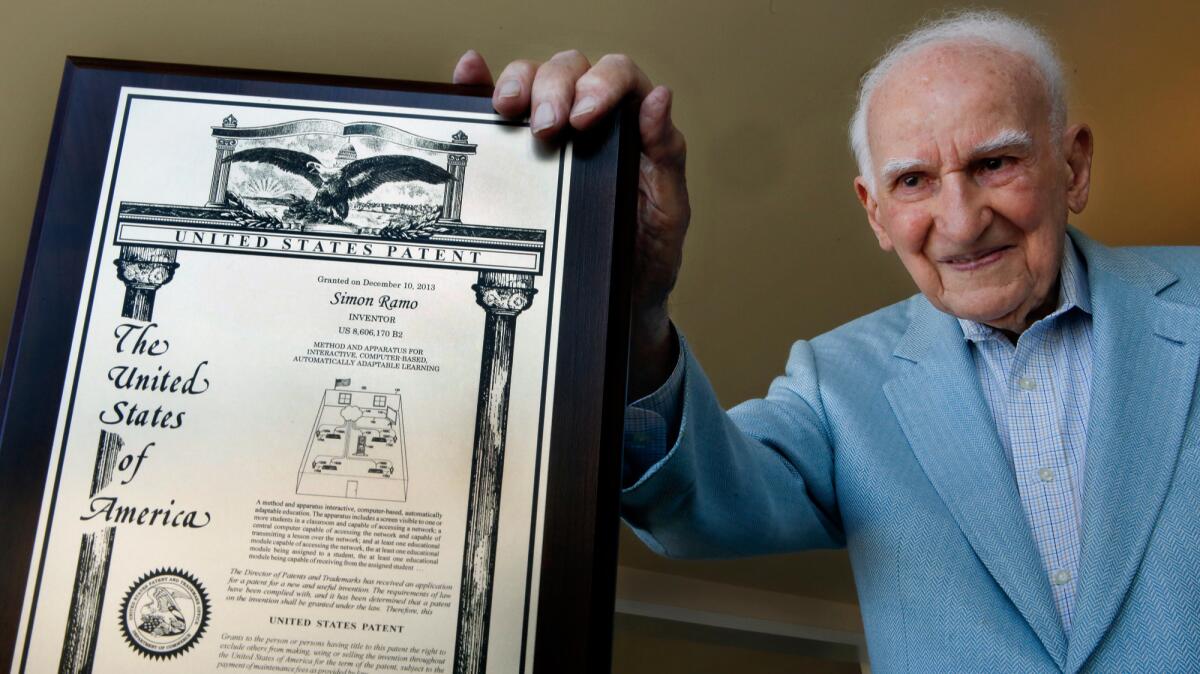

Si Ramo was a skilled amateur musician, an engineering pioneer, a management guru, a builder and teacher. The Utah-born Ramo had come west to study at Caltech in 1933 and joined General Electric before the war. He received his first patent just after his 28th birthday and the last of his portfolio of about 40 at the age of 100, making him the oldest inventor to earn a patent.

By my count he published 18 books on topics ranging from microwaves to tennis. He was retired, formally, but intellectually not at rest; about a year before he died he sent me the manuscript of a work of fiction he was hoping to publish, a somewhat randy tale with a business moral built in.

To be a CEO and to be a political leader each demands about 10 important qualities... [Most] have absolutely nothing in common with each other.

— Simon Ramo, on why business leaders make poor political leaders

Ramo walked with a cane and his once-powerful frame was a bit bent over as he sat at the table. But one could easily detect the air of command he once wielded, and that prompted President Dwight Eisenhower to place the ICBM development program in his hands in the 1950s. He would furrow his brow and fix me with two eyes burning bright, then launch into a penetrating and witty monologue, brimming with the self-effacing humor and deserved conviction in the cogency of his viewpoint that his associates would recognize.

“I’d like to talk about this today,” he’d begin, naming a topic. It might be the virtues of using unmanned drones in warfare rather than platoons of young men and women — his point was encapsulated in the title of his book “Let the Robots Do the Dying” published in 2011 by USC’s Figueroa Press — or the folly of sending humans to explore Mars (on which he wrote a Los Angeles Times op-ed in 2010), or the wastefulness of Pentagon spending to build weapons systems utterly unsuited to 21st century battlefields.

After the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, he wanted to talk about the challenges of systems engineering. As I wrote at the time, Ramo defined the concept as the art of engineering complicated arrangements so the failure of one element — information, communications, apparatus or human beings — wouldn’t destroy the whole.

Even if every element is engineered to the utmost reliability, he explained, “you have to expect failure of a new complicated system — part of the process of getting it right is to find out what goes wrong and cure that.”

Of the Gulf of Mexico spill, he called it “pathetic, sad, ridiculous to not have proper plans properly worked out” and speculated that “systems engineering didn’t have a high priority, and risks were taken that were greater than they should be.”

A question I once managed to get in edgewise concerned the reasons that top business executives tended to fail as political leaders. It was just before election day 2010 and ex-CEOs Meg Whitman and Carly Fiorina were faltering in their campaigns to become California governor and U.S. senator. Although some business luminaries had succeeded in political careers — then-New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg was exhibit A — the graveyards were filled with CEOs’ political ambitions.

TRW co-founder Simon Ramo: the epitome of a “Renaissance man” »

Tales from Simon Ramo, the voice of experience in management »

Why big time CEOs make terrible politicians »

“To be a CEO and to be a political leader each demands about 10 important qualities,” Ramo told me. “Maybe five of those are the same — you have to know how to read a budget and delegate authority and manage people, for example — but the others have absolutely nothing in common with each other.”

His point was that many qualities that make a good CEO are necessary, but not sufficient, to make a good politician, in the same sense that a concert violinist and a neurosurgeon need supple fingers — “but that doesn’t mean you’d want a violinist to perform your surgery.”

Si was happy to talk about the eminent individuals he had known, befriended or worked with over a long and eventful life, such as violinist Jascha Heifetz, with whom he once played a duet. On the “Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson” he explained the secret of tennis success outlined in his 1970 book “Extraordinary Tennis for the Ordinary Player.” Not unexpectedly, the book took a systems approach.

“An ordinary tennis player thinks he should emulate the pros,” Ramo observed. But amateurs reaching for techniques they couldn’t hope to execute just left them exhausted. Instead, he recommended that players adjust their strategy to their skill level, eliminating unnecessary errors.

Howard Hughes was one of the more influential figures in his career, mostly because of his absence. It was right after World War II and Ramo was hoping to move back west with his wife, Virginia. The aircraft industry, which understood that it would have to understand electronics to advance in the postwar world, beckoned.

Ramo met with a team that worked for Hughes Aircraft, and what they told him about their proprietor sounded intriguing. Hughes Aircraft, as Ramo related in 1995 to Frederik Nebeker of the Center for the History of Electrical Engineering, was “a hobby shop” run by a “preposterous eccentric who was horsing around with ridiculous projects.” Hughes Aircraft held contracts with the newly created Air Force, but Hughes himself was barred from direct involvement because he lacked a security clearance (he had refused to be fingerprinted).

“The point is, he didn’t know what was going on,” Ramo said. “He was hardly around, and these fellows were doing whatever they pleased.”

Ramo, who was known to the Pentagon as an expert in guidance systems, came on board and began collecting government contracts. In partnership with Caltech classmate Dean Wooldridge, he stayed with Hughes until 1953, when they and the Air Force finally got exasperated with the mercurial industrialist. Ramo and Wooldridge formed their own company in a refurbished Westchester barbershop. After it merged with the engineering company Thompson Products, they became the “R” and “W” of TRW Inc.

Si and his partner built TRW into a Fortune 500 company, but conventional corporate metrics can’t encompass the mark he left on the lives of his friends and colleagues. For them, the loss is personal.