Column: Why do people still hate Obamacare? Probably because they still don’t know much about it.

Much about our current political climate may be volatile, but one feature seems to be as stable as the Rockies: Americans’ dislike of the Affordable Care Act.

The Kaiser Family Foundation, which has been tracking this sentiment almost since the law’s passage in early 2010 (its latest reading shows unfavorable opinion of Obamacare outpolling favorable 47% to 44%) thinks it may have a clue as to why that is. Its poll also shows that the vast majority of Americans still have no idea about what the law has accomplished.

Specifically, some three-quarters of the country isn’t aware that Obamacare has reduced the ranks of the medically uninsured to an all-time low. One in five respondents to the foundation’s poll (21%) believed the uninsured rate was at an all-time high. A plurality of 46% thought the rate is “about the same as it has been.” Only 26% of respondents knew that the uninsured rate of 10% among the nonelderly population marks a record low.

Without knowledge of the facts, people are more susceptible to spin and misrepresentation.

— Kaiser Family Foundation Chief Executive Drew Altman

“Why don’t more people know this?” asks the foundation’s CEO, Drew Altman, in a Wall Street Journal op-ed. “It’s not that the news media have failed to cover the story. There have been regular news reports about government and private surveys showing progress on this issue because of the ACA.

Altman thinks one factor may be that many Americans — 29 million — do remain uninsured, and the public may see them “among their family and friends or in their community as often or more often than they see the newly insured.” Some may be swayed by negative news reports about rising healthcare premiums, or the withdrawal of some big insurers from the individual markets. Those reports have “colored perceptions of progress in other areas, including on the uninsured rate.”

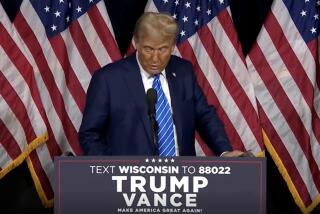

One other factor, which Altman downplays, is partisanship. But partisan misrepresentation of the law is nearing an all-time high just now. During last Sunday’s presidential debate, Donald Trump declared the ACA to be “a total disaster,” though he proposed no remedies other than that “it has to be repealed and replaced.” Hillary Clinton, by contrast, calls for improving the law by expanding premium subsidies and expanding Medicaid, among other proposals.

The candidates’ focus on the law during this campaign, intermittent as it is, may have something to do with the spike in both the ACA’s unfavorable and favorable numbers in the Kaiser Family Foundation poll. While the unfavorable figure jumped to 47% in September from 42% in August, the favorable result also rose, to 44% from 40%.

Americans never have been really familiar with the law’s numerous provisions and how they interact. That’s one reason that they often view it as simply the individual insurance exchanges, which work superbly in some states (California, for instance) and wretchedly in others. The difference often is connected with the extent to which state governments have embraced the law — in places where governors and legislators have done their best to hamper its effectiveness, they’ve succeeded.

Almost from Obamacare’s inception, pollsters have noticed that specific provisions of the law get high marks from the public — the end of discrimination for preexisting conditions and the outlawing of lifetime limits on insurance coverage — but the law itself gets low marks, especially when it’s described as “Obamacare.” It’s difficult to explain this other than by referring to the sedulous campaign by its enemies, especially Republicans, to paint it inaccurately as a “government takeover” of healthcare or merely to label it a “disaster.”

The ACA’s supporters among leading Democrats deserve a good measure of blame, too. They’ve seldom defended the law with the vigor it deserves — so why should they be surprised that the GOP has seized the opportunity to define it for voters?

Altman does recognize this factor at play. “Without knowledge of the facts, people are more susceptible to spin and misrepresentation,” he writes. Although the law has brought insurance to 20 million Americans who didn’t have it before, that fact gets swamped in the debate, in part because it’s treated as old news. “The data may not be new research or a fresh sound bite,” he concludes. “But if informing the public on big issues under debate is a goal, new ways may need to be found to get the facts out again and again.”

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email [email protected].

Return to Michael Hiltzik’s blog.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.