How free college tuition would become a giveaway to the rich

A linchpin of Bernie Sanders' campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination is his proposal for free tuition at public colleges and universities for all students. But who would really gain from the deal? Sanders implies that it would be a boon to the working class and low-income families. But a recent study by the Brookings Institution suggests just the opposite -- that the biggest gains would be reaped by upper-income kids.

Although the Sanders movement is ebbing as a quest for the nomination, he's determined to stay in the race to influence the Democratic platform. The issue of college costs and the debt burden of graduating students is likely to remain a live one -- Hillary Clinton, who is all but assured the nomination, has proposed her own relief plan for college costs. Her proposal targets student aid to middle- and lower-income families, rather than eliminating all tuition at public universities.

Last year, Germany eliminated tuition because they believed that charging students $1,300 per year was discouraging Germans from going to college.... If other countries can take this action, so can the United States of America.

— Presidential candidate Bernie Sanders

Let's take a look.

"This is not a radical idea," Sanders says on his policy Web page. "Last year, Germany eliminated tuition because they believed that charging students $1,300 per year was discouraging Germans from going to college.... If other countries can take this action, so can the United States of America." He notes that until the 1980s, tuition was free at the University of California for in-state students, a policy we've advocated be restored.

Some details of the Sanders plan are nebulous, as typically happens with campaign platforms. He says the plan "would require public colleges and universities to meet 100% of the financial needs of the lowest-income students," who would in turn be able to use federal, state and college financial aid to cover room and board, books and living expenses outside of tuition.

The plan obviously would require each individual state to agree, since the federal government can't mandate such a policy. Sanders estimates the cost would come to $75 billion a year, which would be covered by "a tax of a fraction of a percent on Wall Street speculators who nearly destroyed the economy seven years ago." This is a crowd-pleasing reduction of the basic tax plan, which is a transaction tax on stock, bond and derivatives transactions (not all of which are done by "speculators"). But he's right in stating that a transaction tax is a popular idea among some economists, who think it would tamp down unnecessary trading and raise money from activities that should contribute more to the tax base. An analysis by the progressive Center for Economic and Policy Research is here.

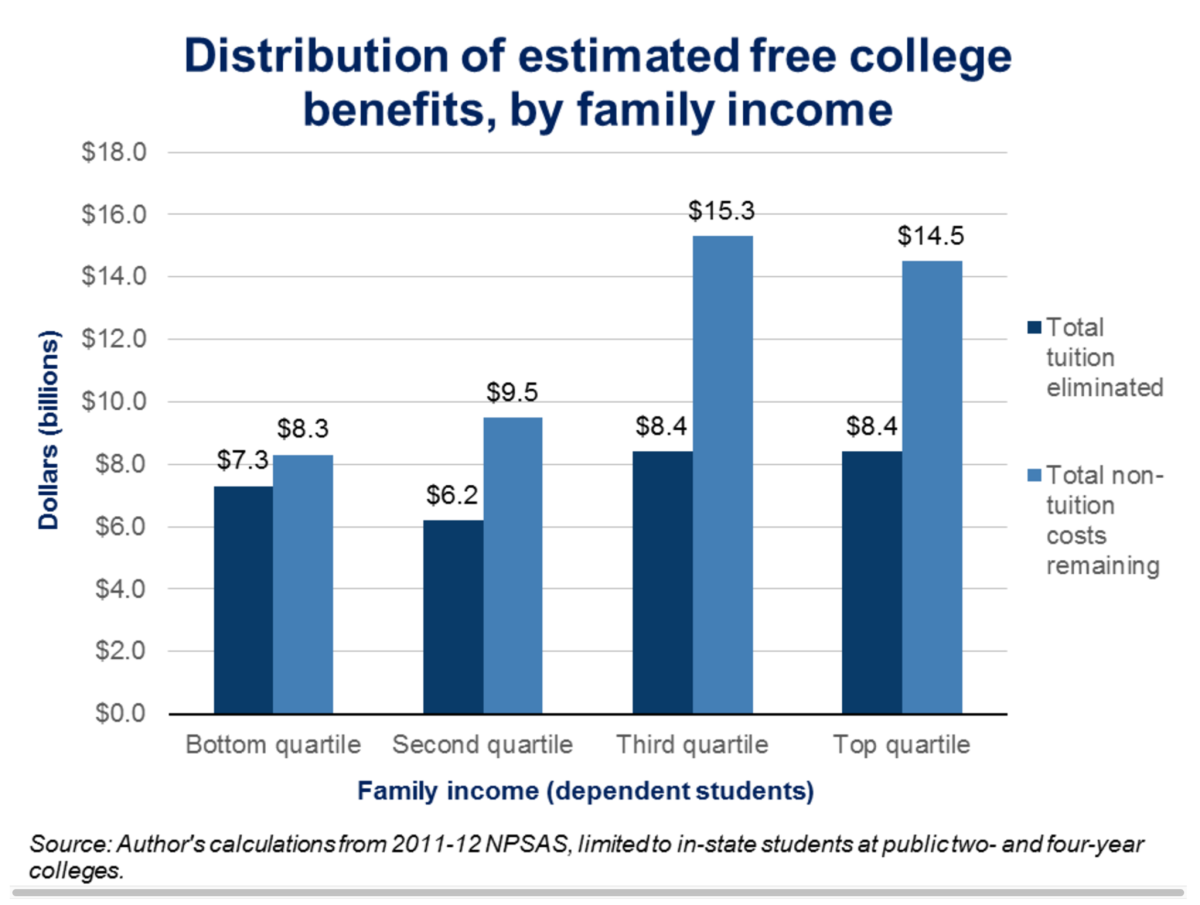

But who would gain? That's where the Brookings-published study by Matthew M. Chingos, a fellow at the Urban Institute, comes in. Chingos notes that students from lower-income families generally attend lower-cost community colleges, while higher-income students tend to enter more-expensive four-year institutions: "Students from families in the top income quartile attend colleges that charge about $1,200, or 20 percent, more than the colleges attended by the typical student from the bottom income quartile," he writes. "Students from the most affluent 25 percent of families represent 11% of students at public colleges, but would receive 18% of the benefits if tuition were eliminated."

As for non-tuition costs, they still remain to be paid for by all families. Although some government assistance is available for university expenses, most aren't covered by "existing federal, state, and institutional grant programs," Chingos says. For the students from the lower half of the income spectrum, those out-of-pocket costs come to $17.8 billion. The irony of the Sanders plan is that those costs could be largely covered out of the $16.8 billion going to wealthier students in the form of free tuition. Deciding to pay those students' tuition instead of devoting the same sums to the out-of-pocket costs of poorer students is a trade-off that isn't made clear in the Sanders plan.

Chingos acknowledges that a lot is left out of his analysis, such as how free tuition would affect attendance rates in various income segments. It's possible that enrollment would rise among low-income students overall, but it's also possible that it might fall relative to wealthier students, "if competition for places at public colleges increases as higher-income students shift from the private to the public sector given the change in price."

Assuming that low-income students would gravitate toward cheaper two-year colleges and universities may seem like an unfair prejudgment, but it's proper to note that students from wealthier school districts emerge better-trained for college than those in poor districts. That implies that some of the money Sanders would devote to higher education might be better spent shoring up public secondary schools.

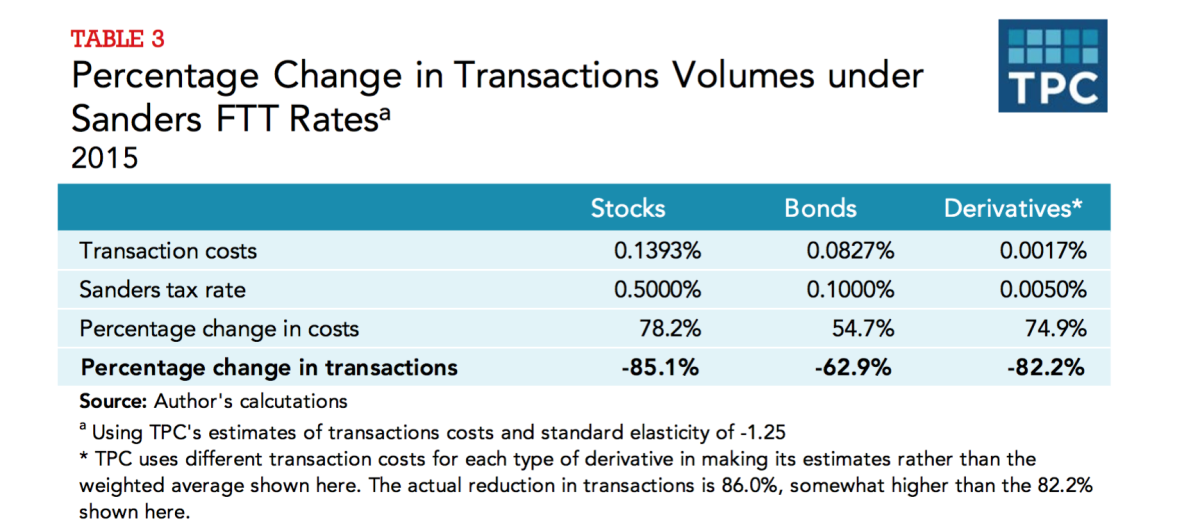

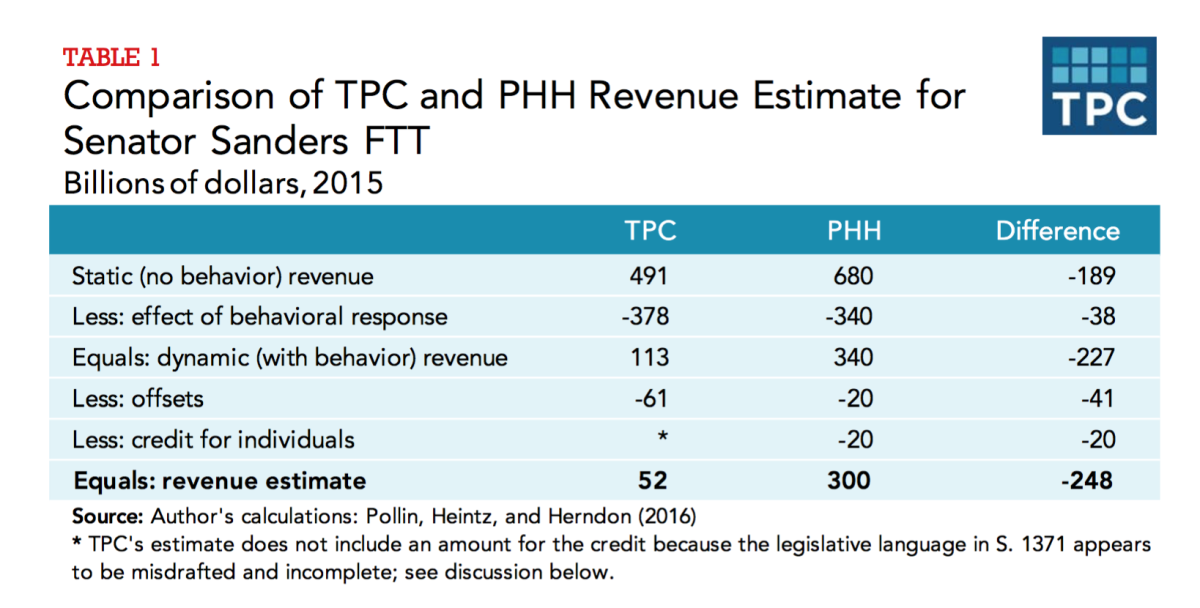

What about the tax side of the Sanders plan? That has also come under attack by experts who say it's unlikely to bring in anything close to the annual $300 billion estimated by the Sanders campaign. James R. Nunns of the Tax Policy Center faults the Sanders analysis for underestimating how much the tax would reduce financial transactions, which of course reduces the tax take. That's odd, given that one rationale for the transaction tax is that it would reduce unnecessary trading. The Sanders tax analyzed by the TPC would come to half a percent on stock trades, one-tenth of one percent on bond trades, and five thousandths of a percent on trades of derivatives such as options. Initial public offerings and trades of tax-exempt bonds would be exempt. That's enough, the TPC reckons, to reduce the revenue from the plan to $52 billion a year from $300 billion -- not enough to fund Sanders' tuition plan.

Given the attention being devoted to the rising debt load of graduating university seniors and professional school students, the question of how to pay for higher education is sure to remain on the table, regardless of the outcome of November's election. Whether the best approach is to attack costs at the source -- the budgets and tuition charges of colleges and universities -- by steering grants to needy students, or helping students borrow at manageable rates and terms is still open.

But Clinton's critique of the Sanders plan -- that it would amount to providing free college to Donald Trump's kids -- is an apt one, if metaphorical. (His grown children attended private universities, and his youngest child is nine.) The U.S. desperately needs an answer to rising college costs. Sanders' proposal is a good device for focusing public attention on the problem, but it's only a start.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email [email protected].