Column: Employers will do almost anything to find workers to fill jobs — except pay them more

UPDATE, July 12: In its latest report on wages, released Thursday, the Bureau of Labor Statistics said that earnings for all employees were unchanged in June from June 2017. Real average hourly wages increased 0.1% in June from May, because half of a 0.2% increase in average hourly earnings was eaten up by a 0.1% increase in the Consumer Price Index.

Real average hourly earnings for production and nonsupervisory workers actually decreased by 0.2% over the past year, the BLS said.

The average work week increased by 0.3% over the past year, resulting in a 0.2% increase in real average weekly earnings over the past year, and no change in the figure for production and nonsupervisory workers.

________________

Of all the addictions that undermine stability in communities and society at large, surely one of the worst and most persistent is the addiction of corporate managements to pleasing their shareholders.

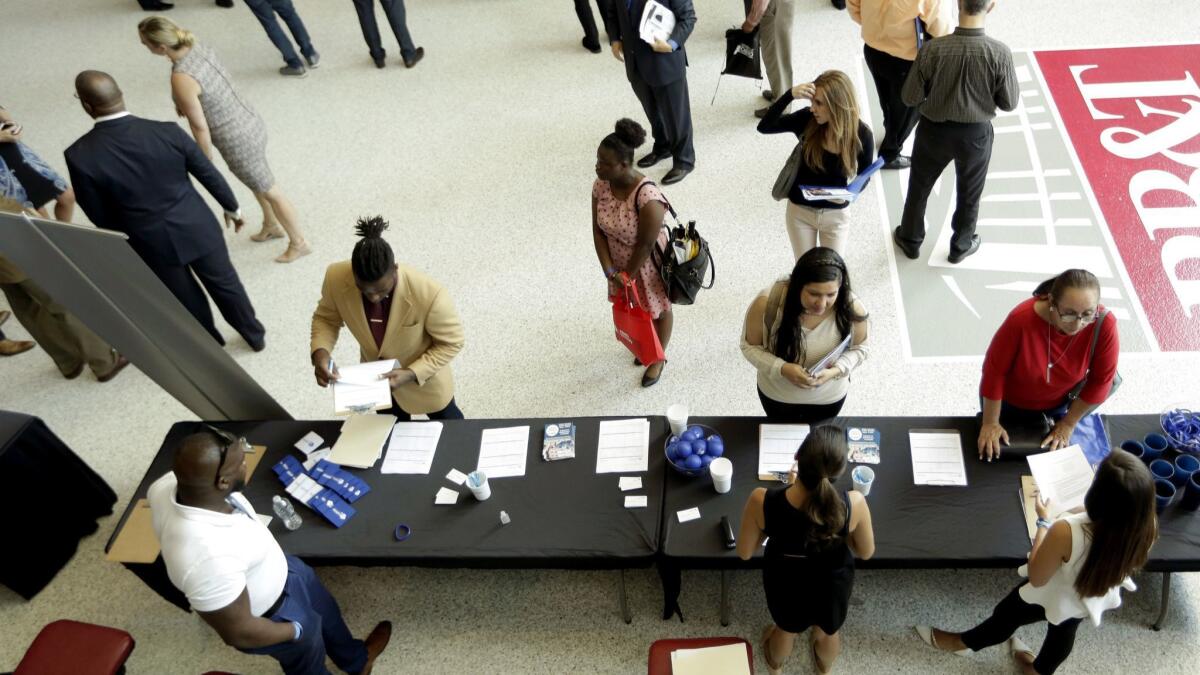

Billions of dollars are funneled to owners of capital in the form of dividends and stock buybacks, while laborers go begging for even the measliest wage increases. In recent days and weeks we’ve seen the process play out for the umpteenth time, as businesses grouse about a labor shortage even as job openings increase.

“America’s labor shortage is approaching epidemic proportions,” reported CNBC, “and it could be employers who end up paying.” Well, yes. That’s how things are supposed to work: Businesses pay more to attract workers in a tighter, more competitive market for labor.

Labor is being paid first again. Shareholders get leftovers.

— Citigroup securities analyst bemoans a wage hike at American Airlines

The rhetoric coming out of the employer lobby would leave one to believe that workers are somehow the guilty party in this — they simply won’t accept jobs that pay them less than they’re worth.

The underlying cause of the “labor shortage” is hiding in plain sight. It’s the long-term trend of funneling the gains from labor productivity not to the workforce, but to shareholders. As with any addiction, this process produces short-term euphoria, reflected in share prices, but long-term pathology, reflected in income inequality, poverty and social unrest.

But it’s been going on so long that the addicts, that is, corporate CEOs and their mouthpieces, have forgotten how to respond. The CNBC piece observed, as though this is a new discovery, that “employers are going to have to start doing more to entice workers, likely through pay raises, training and other incentives.” The harvest will be lower corporate earnings, Goldman Sachs has warned.

According to the Wall Street Journal, Goldman’s economists “predict that every percentage-point increase in labor-cost inflation will drag down earnings of companies in the S&P 500 by 0.8%.” That money won’t disappear, of course—it will go into the pockets of workers, and then find its way back into the coffers of corporate America via higher sales.

The narrow attitude that wage growth is bad for business is exemplified by the pummeling that American Airlines suffered from Wall Street a year ago, when it announced healthy wage increases for pilots and flight attendants, even before their union contracts expired. As we reported at the time, the airline’s shares lost more than 8% in value over the ensuing two trading sessions, a loss of about $1.9 billion in market value in 48 hours.

“Labor is being paid first again,” Kevin Crissey, an airlines analyst for Citigroup, bellyached to clients after the announcement. “Shareholders get leftovers.” Hardly: From 2014 through 2016, American had authorized $9 billion in share buybacks to fatten the shareholders’ take. By contrast, the pay raises will cost American $1 billion over three years.

Let’s take a look at how the balance between corporate profits and labor compensation has changed just in the last couple of decades, and how resistant employers have been to responding sensibly.

As a share of gross domestic income, corporate profits have nearly doubled, to 6.4% in 2016 from 3.3% in 1990, according to figures from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Meanwhile, the labor share, measured as wages and salaries paid to individuals, has been on a schneid, falling to 42.2% in 2013 from 46.2% in 1991. The labor share has since crept up to 43% as of 2016, but it’s still well below its postwar peak of 51.5%, reached in 1970.

As a reflection, if not a cause, of this trend, wages have been stagnant since the early 1980s. Hourly wages, adjusted for inflation, have been mired at about 80% of their level in 1960. They soared to more than double their 1960 level in the mid-1970s, then fell sharply during the recession of the early 1980s and never recovered. To the extent there has been job growth, it has been at the lower end of the income scale, in part because wage scales for what once were middle-class or lower-middle-income jobs have been downsized.

It may be no coincidence that the shift of income toward shareholders and away from labor followed by only a few years conservative economist Milton Friedman’s declaration of “shareholder value” as the guiding philosophy of corporate management. Friedman took his stance in a New York Times article in 1970. At first, business leaders disdained this view as too narrow.

But it didn’t take long for CEOs to divine the wisdom of a viewpoint that hit them where they lived, in their wallets. The harvest has been decades of increasing income and wealth inequality.

Today’s lament about the dearth of employable workers is the reprise of an old tune; Cardiff Garcia of the Financial Times collected a few old cover versions, which seem to get released to the airwaves on almost an annual basis. The tune never changes, but the dime never seems to drop for corporate leaders.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email [email protected].

Return to Michael Hiltzik’s blog.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.