David Graeber looks at the Occupy movement, from the inside

“It’s a difficult business,” writes David Graeber, “creating a new, alternative civilization.”

Just open a window or turn on the TV — the same old civilization is rotting all around us. Budget cuts, police shootings, endless and ever-broadening wars, the climate in full-scale, almost-end-times spasm, a Congress of hand puppets yelping on about the manufactured crisis of the moment, a president whose answer to every crisis is More of the Same. Analogous situations have, over the last four years, lighted the streets on fire in Britain, France, Spain, Ireland, Latvia, Italy, Greece, Chile, Tunisia, Egypt, Bahrain and Syria, to name a few.

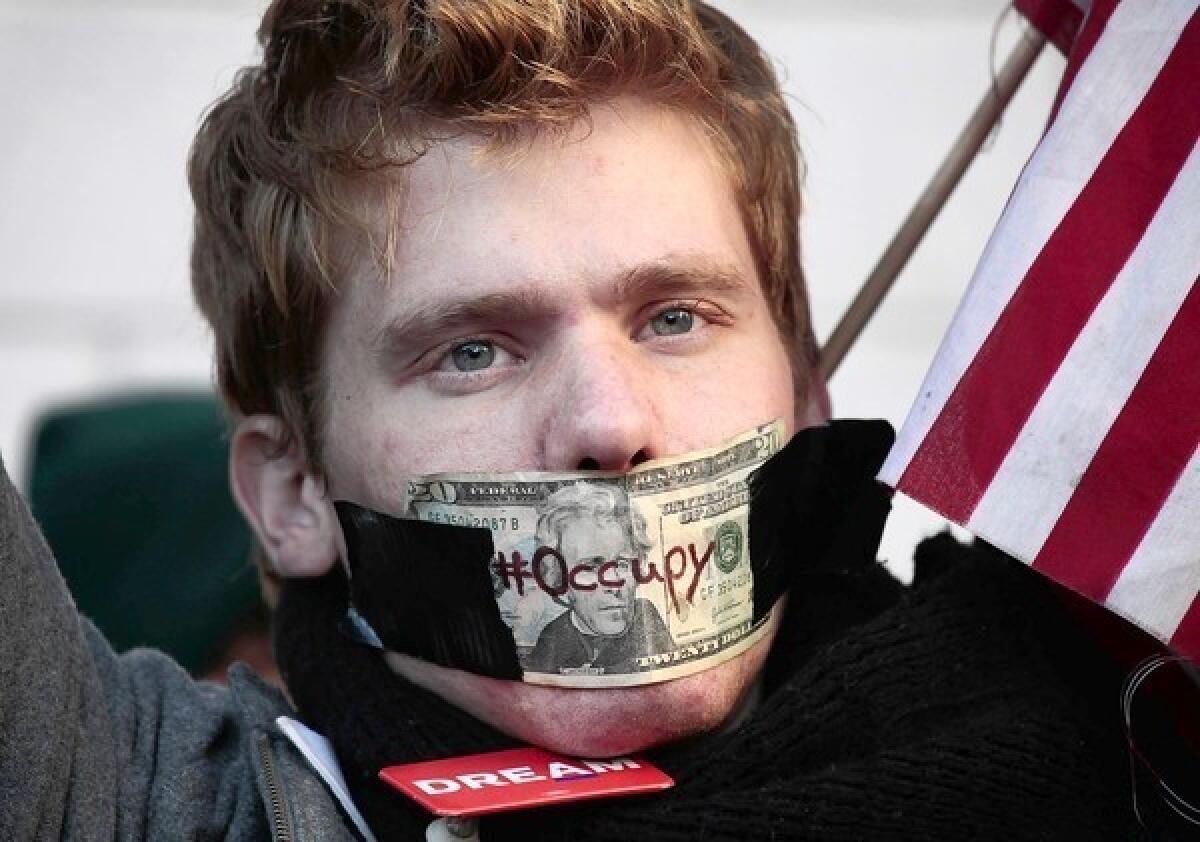

There was, in 2011, a brief exception to this sad form of American exceptionalism. Remember Occupy Wall Street? On Sept. 17 of that year, 2,000 people filled New York’s Zuccotti Park. A few hundred stayed the night, and the night after that. “We are the 99%,” they declared.

The slogan caught on. Soon, the crowds were swelling to the tens of thousands. Police attempts to contain the movement — with pepper spray, beatings, mass arrests — only helped it to spread. Within weeks, there were occupations in more than 500 American cities and towns: In California, not only in Los Angeles and Oakland but also in Riverside, Torrance, Fresno....

In mid-November, the sword came down. In one city after another, police stormed the encampments, tore down the tents, trashed the libraries and clinics, arrested anyone who happened to be nearby.

Anthropologist David Graeber, who was then teaching at Goldsmith’s College in London, happened to be in New York that fall. Graeber’s anarchist politics, scholarly virtuosity and long history of activism had already earned him a measure of stardom among left intellectuals, a celebrity that would grow exponentially with the publication of his monumental and often brilliant book “Debt: The First 5,000 Years” in July 2011.

Two months later, Graeber helped organize Occupy Wall Street’s first general assembly meeting.

“The Democracy Project” provides a rather hurried insider’s view of the Occupy movement’s beginnings and a far-too-cursory account of its collapse. To the same degree that “Debt” was meticulously and deliciously detailed, “The Democracy Project” feels scattershot and rushed, as if Graeber hadn’t decided whether he was writing a from-the-ground tale of Occupy, a myth-busting history of democracy in early America or a mass-market “Anarchism for Dummies.” He never quite commits to any one approach or takes sufficient effort to tie them all together. The results are as frustrating as they are intriguing.

At the center of Graeber’s project is an attempt to rescue the Occupy movement from the irrelevance to which most pundits assigned it. Graeber deftly diagnoses the corporate media-imposed “straitjacket on acceptable political discourse” that guarantees that raising certain questions — about, for instance, the plutocratic and frankly kleptocratic nature of a system in which government bows before a financial services industry whose main “service,” he points out, is the creation of bottomless consumer debt — marks you as an extremist lunatic unfit to be heard on the air. “The result,” he writes, “is a mainstream ideology … which almost no one actually holds.”

Enter Occupy, which by refusing to issue set demands allowed the unemployed, the debt-burdened, the anxious and the angry an almost unprecedented public forum to analyze their situations.

Its reliance on anarchist modes of consensual decision-making turned Occupy, Graeber argues, into a vast experiment in radical democracy of a sort heretofore unseen in the U.S. (The authors of the Constitution, he reminds us, were more interested in constraining the democratic urges behind the American Revolution than in unleashing them.)

Occupy, he writes, spurred a “revival of revolutionary imagination that the conventional wisdom has long since declared dead.”

Graeber’s purpose in “The Democracy Project” is two-fold: first, to make a reasoned case for revolution, arguing that our ostensibly democratic system had become so servile to the whims of the financial elite that “the only way to restore us to lives of minimal decency was to come up with a different system entirely”; and second, to rehabilitate anarchism, that most scorned and misunderstood of political philosophies, and place it at the center of the Occupy narrative.

Occupy, Graeber argues, was an almost inconceivable thing, a mass, mainstream American anarchist movement.

“The movement did not succeed despite the anarchist element,” he writes. “It succeeded because of it.”

“The Democracy Project” is thus not so much a history of the Occupy movement as a polemic about that history, about Occupy’s role within American politics and anarchism’s role within Occupy. But many of Graeber’s most intriguing insights — on, to choose one of many, our debt to pirates and the Iroquois for what little democratic tradition we have — are left underdeveloped. Instead, we get a chapter-long primer on anarchist decision-making, complete with FAQs. Reading about the consensus process, alas, is nearly as excruciating as sitting through meetings in which it is employed.

Frustratingly, Graeber’s insistent optimism requires that he claim that Occupy was not defeated when the camps were torn down, that it was in fact a success, the full impact of which will not be felt for years.

“Once people’s political horizons have been broadened,” he writes, “the change is permanent.” This is unfortunately untrue (recall the so-called generation of 1968), and Graeber’s sunniness prevents him from grappling with any of Occupy’s real failings.

Most of the political ills he diagnoses in the U.S. disproportionately affect people of color, but Occupy remained, he admits, a largely white, middle-class movement. The issue of race is nonetheless entirely absent from Graeber’s accounts of Occupy and of American history, a worse than startling omission.

And although it was hardly the occupiers’ fault that they were unable to withstand the waves of police violence that cleared camp after camp across the country, Graeber’s lack of reflection on the question of how to counter such brutality is disturbing. “Violence is the preferred tactic of the stupid,” he writes dismissively.

Zuccotti Park is once again a pleasantly sterile spot in which bond traders can sit and eat lunch. For the moment, the stupid are looking pretty smart.

Ehrenreich’s most recent novel, “Ether,” was published in 2011 by City Lights Press.

The Democracy Project

A History, a Crisis, a Movement

David Graeber

Spiegel & Grau: 311 pp, $26

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.