William Trevor never put a foot wrong: ‘Last Stories’ is exceptional

Some writers flash in pans and extinguish. Others grow old and peter out like neglected pensioners in care-homes. But there are also those rare, exceptional writers who are fortunate enough (like their readers) to burn bright and steady over many decades, expressing the same creative clarity at the end of their careers as they did at the beginning. William Trevor was one of those writers.

Over more than 50 years of humanely focused and always-inventive literary production, Trevor wrote about the sorts of people that other people don’t always see: elderly spinsters living alone with their dogs, divorced inebriated urban dads trying to make the most out of an afternoon visitation, working girls in the Irish countryside seeking romance at tacky dance halls, and children from the leafy suburbs who never outgrow their sibling rivalries, or even leave the home where those rivalries were initially engaged. And while Trevor’s novels were memorable — most notably “The Story of Lucy Gault” (2002) and “Felicia’s Journey” (1994) — he is one of the rare contemporary writers (along with Alice Munro and Raymond Carver) who established wide and eager readerships based primarily on the strengths of their short story collections.

Beginning with “The Day We Got Drunk on Cake” (1967) and concluding with this lovely and exceptional book of “Last Stories” assembled mainly from the New Yorker and published together more than a year after Trevor’s death, this wonderful writer never put a foot wrong. In the first, early stories, his characters were somewhat brighter and more comic — such as the retired General Suffolk, who avoids his cleaning woman every week by wandering through town, drinking too much and annoying the locals; or the macabre, broody middle-aged couple, the Dutts, who are so hungry for children that they adopt elderly men and women to reside (and eventually die) in their back bedroom. (These early stories often resemble the suburban comedies of Cheever or Kingsley Amis, and are just as good now as when they were originally published in the early 1960s.) In later years, Trevor’s stories grew more shaded, muted and melancholy. They have a clean, simple, single-brush-stroke quality to them, at once sparely written and moodily structured. They can’t adequately be compared to the stories of anyone else.

As in “The Hill Bachelors” (2000) or “Cheating at Canasta” (2007), “Last Stories” draws readers into accidental glimpses of ordinary lives — and once those lives are glimpsed, they don’t seem ordinary at all. In “The Piano Teacher’s Pupil,” Miss Nightingale has been waiting all her life for a student like the mysterious boy who arrives in her home one afternoon and plays Brahms as if he was born to do it; then, before he leaves, repays her gratitude by stealing little items from her house — an earring, the lid from a pot, a scarf, a porcelain swan — reminding her of the little chocolates she used to steal from her father, a chocolatier. (Many of these late stories are about remembering the aimless, unforgettable kindnesses of parents.) In “At the Caffè Darria,” a middle-aged woman takes her daily meals in a mid-priced local restaurant in order to (like many Trevor characters) feel at home among strangers; and here she encounters the woman who lived with her ex-husband until he died, and they both learn about what each of them has lost and gained. And in “An Idyll in Winter” (my favorite story in the collection), a man leaves his family for a girl he once tutored in the lonely, Bronte-like moors of northern England until he is eventually called home by the suffering of a daughter who may love him too much.

Most of Trevor’s stories are about how old affections get lost when new affections come around. (In fact, the old ones never seem to quite go away at all — which is, of course, the problem.) In one of this volume’s most moving stories, “Giotto’s Angels,” a prostitute is led home by an amnesiac art-restorer to find a secret life that possesses more beauty and purpose than her own. Envying what she finds, she steals money from his closet (money that he probably doesn’t even remember he has) and tries to return to her own life; but the man lives on in her mind as a never-quite-forsaken memory of plenitude:

You couldn’t forget it. You couldn’t forget the conversation of the afflicted man, or how he was skillful with the brush and the paint, like a man brought back from the dead as soon as he had them by him. You couldn’t forget the way he knew how to guide the little paintbrush into whatever part of the picture was defective and the colour coming then, how he’d do it without ever a hesitation…. He was secure where he was, as if the emptiness around him protected him.

Most of these last stories, appropriately enough, are about not forgetting: the young girl who can’t forget the mother who left her when she was 2 years old in “The Women”; or the lost middle-aged woman who can’t forget a handsome middle-aged man she meets in the street in “Mrs. Crasthorpe”; or the single mother and her college-aged son who can’t forget the quiet young woman who once worked for them in “The Unknown Girl.” But most of all, William Trevor’s last stories (much like his first ones) are about not forgetting this marvelous, beautiful and unusual writer who never stopped producing great work until he died.

Which seems only fair — since these are stories that never seem to forget about us.

Bradfield is the author of a dozen books including, most recently, the novel “Dazzle Resplendent: Adventures of a Misanthropic Dog.”

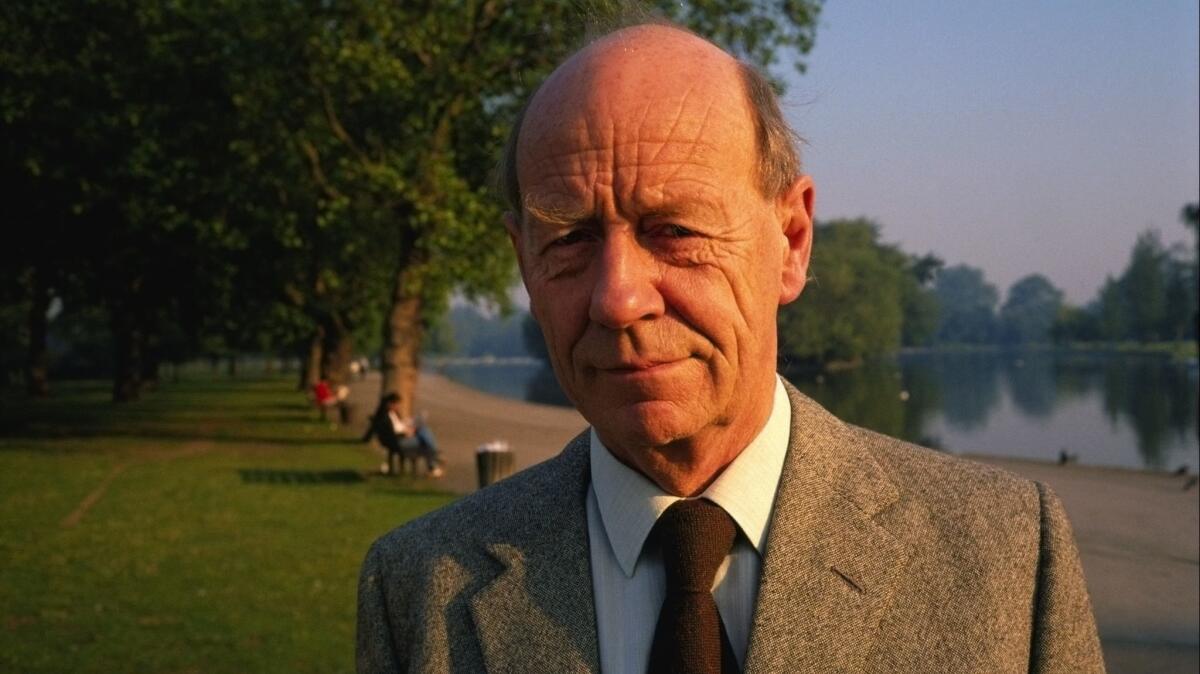

William Trevor

Viking: 224 pp., $26

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.