Punk’s not dead: Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain and ‘Please Kill Me’

They came not to bury punk but to praise it. 20 years ago, Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain published “Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk” with Grove Press. The format was ingenious — no single person could lay claim to know the whole of the sprawling, anarchically creative, drug-riddled scene.

Not even McNeil, Punk Magazine’s “resident punk” from its founding in 1976 through its 1979 end, who couldn’t bring himself to write a memoir. “I thought, how boring,” he says. “My story?” It took the help of McCain, a friend, fellow lover of oral histories and patient co-conspirator, to make the project come together.

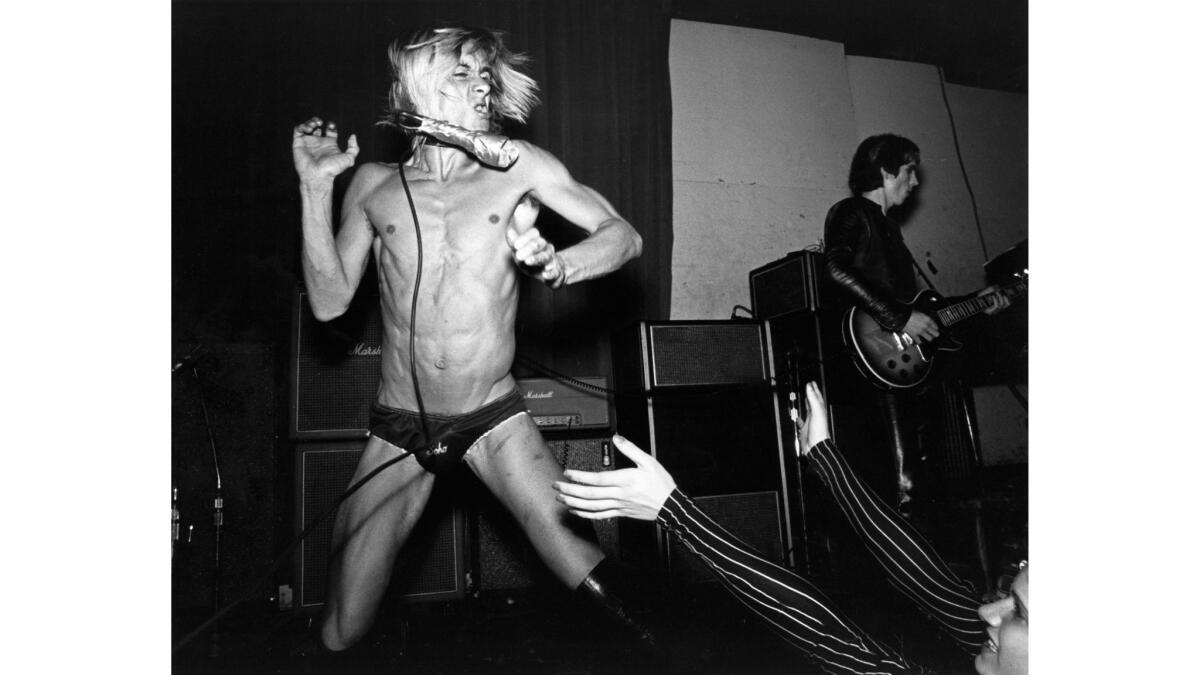

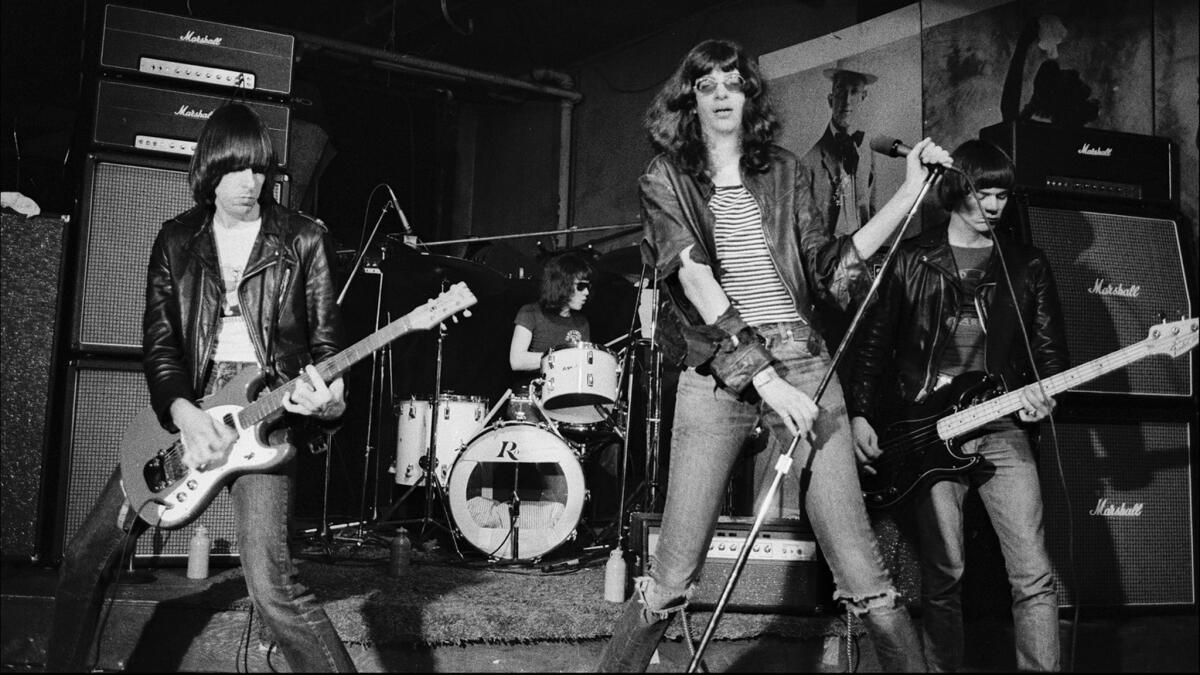

“Please Kill Me,” five years in the making, was important not just because it made visible the genealogy of an underground music scene (the Velvet Underground to the New York Dolls to the Stooges to Television, Blondie and the Ramones) but because it showed how brilliantly an oral history could capture culture. Previously, histories like it had been rare — McNeil and McCain were primarily inspired by “Edie” by Jean Stein, edited by George Plimpton — but now they’re everywhere, with “Freaks and Geeks,” the March on Washington and lobster rolls getting the oral history treatment.

I sat down with McCain and McNeil in downtown L.A. — at the Ace Hotel, where Michael Des Barres hosted their Aug. 1 reading for an audience that included Blondie’s Clem Burke — to talk about the project as part of our occasional Collaborators series. Although they are not a couple (McCain is married to music writer James Marshall), they frequently finish each others’ sentences. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Legs McNeil: We read the Truman Capote excerpt in the New Yorker, and we both went out and bought the oral history. Remember that? It was so disappointing. That one chapter was good, that they excerpted. But the rest of the book was not.

Gillian McCain: That made me see — that was just [written by] George Plimpton. It made me think, you really need two eyes. I came on board about a year [into the process]. So he’d done tons and tons of interviews before me.

LM: Yeah but I always remember you being there.

GM: I was there as a friend, but I wasn’t in on the interviews. We were talking about it.

LM: We were always talking.

GM: This is the bad thing: People who knew Legs well would come in and say, [does a New York accent] “You know everything.”

Legs has a theory that the reason people were so frank is they didn’t think the book would get published.

— Gillian McCain

LM: You know, it was just part of their everyday lives. Like, Richard [Hell, the musician and writer] and Roberta [Bayley, the photographer], they didn’t want to talk about it. “You know everything. What’s there to talk about?”

GM: Legs has a theory that the reason people were so frank is they didn’t think the book would get published.

LM: I’m really good at structure. Gillian’s great at imagining bigger stuff. There was a part in the book about Duncan Hannah [the painter] going to the Deauville Film Festival. Gillian was like, “This has to go in.” I go, “No way is this … going in.” And then at one point I realized, right before everything falls apart, everybody has to realize what their rock-’n’-roll fantasy is. So for Richard Lloyd [Television guitarist] it’s copping dope in a limousine; for Duncan it’s going [to the film festival] — and then everything goes down. I know that if you were really adamant about something, I’d really have to reconsider.

GM: I think [I’m responsible for] maintaining the integrity of the voices. Sometimes he’d over-edit, and I’d go back. … About the structure: We had certain key points. We knew we were going to start with the Velvets and then go to Detroit. We knew which bands. We knew we wanted to show it started in New York. Other than that I think we kind of learned as we went along.

LM: Doing an oral history, you have to stay very loose. Because if you get a great story that moves the narrative forward, you’ve got to use it. … Gillian and I are very in sync. When we were doing an interview then, when somebody said something, we’d look at each other very knowingly.

GM: And know where it was going to go.

LM: We’d know exactly where it was going to go.

GM: In the book … we wanted the people to tell the story, so we only learned where the story was after we interviewed people.

LM: We didn’t know the whole story. We kept having to go back to Ann Arbor, to the Ashetons’ house. To Kathleen and Ron and Scott [of the Stooges], you know.

GM: [Taking the train to the interview the Ashetons in Michigan] We’d have to get off at Toledo because Detroit, the train didn’t stop there.

LM: No, Cleveland.

GM: No, Toledo.

LM: We had to walk up the hill —

GM: — with suitcases —

LM: — in the ice.

GM: A lot of people it took going back [to re-interview]. The more famous people were really busy.

LM: I was surprised how many people agreed on things. I thought there would be much more of people disagreeing and saying no, that’s not what happened.

GM: There were interviews that started out really bad, like Richard. He was like, [New York accent] “You know all the stories. I’ve told them a million times. What kind of book are you doing? What is this?” He was so grumpy. I left there and I didn’t think it was a great interview, but it was fantastic once we got it transcribed.

LM: We had three transcribers, two full-time ones during the day and one nighttime. So it was around the clock.

GM: We printed them out and put them in binders.

LM: When we found someone who was good — you’ve got to have really good talkers, you know — we just stayed on ’em.

GM: Danny Fields, [the writer and music executive] he was like Zelig.

LM: Yeah, he was everywhere. When Danny and Lisa Robinson [the music writer] walked into CBGBs, you got a little more sober, you stood up a little straighter. He was always chewing gum, he had glasses, and he’d be staring at you. “What are you up to?” Johnny Ramone would give him that military, “Hi Danny.”

GM: Well they had begged him to come down.

LM: This is after he was already managing. Everybody would be fooling around, you’d be picking up girls and stuff, and when Danny and Lisa came, they were like the adults. It was kind of like the insane asylum the rest of the time. It was really fun.

GM: Danny would have been about 15 years older, maybe?

LM: Yeah. I was the youngest kid on the scene, until Howie showed up.

GM: Howie. [D Generation bassist who DJd their L.A. event at the Ace].

LM: Howie showed up and I got so pissed at him. Because he was younger.

GM: Howie Pyro.

Doing an oral history, you have to stay very loose. Because if you get a great story that moves the narrative forward, you’ve got to use it.

— Legs McNeil

LM: Howie was fun. And he had great hair. That’s what really pissed me off. Howie had Johnny Thunders’ hair. In fact, in the book, he goes to Cleveland and they think he’s Johnny Thunders.

GM: And he just goes with it.

LM: Then Chrissie Hynde calls, “I just saw Johnny Thunders, he’s right here in New York” and busted him. They were getting him lots of coke and everything. It was really funny. Howie’s great.

LM: We have thousands and thousands and thousands of interviews. I have ’em all up on my wall. Rooms with walls and walls of cassettes.

GM: You know what I learned? Our cassettes should be like this [holds hand up vertically] not like this [moves it horizontally].

LM: So now we’re digitizing them.

GM: We started working on this in 1991. It was pre-Internet. Isn’t that amazing?

LM: I would call her in the morning, she’d go “Hello?” and I’d go “Such degradation.” We kind of lived in the book for about four years. It was fun. And we would play air guitar to “No Fun.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.