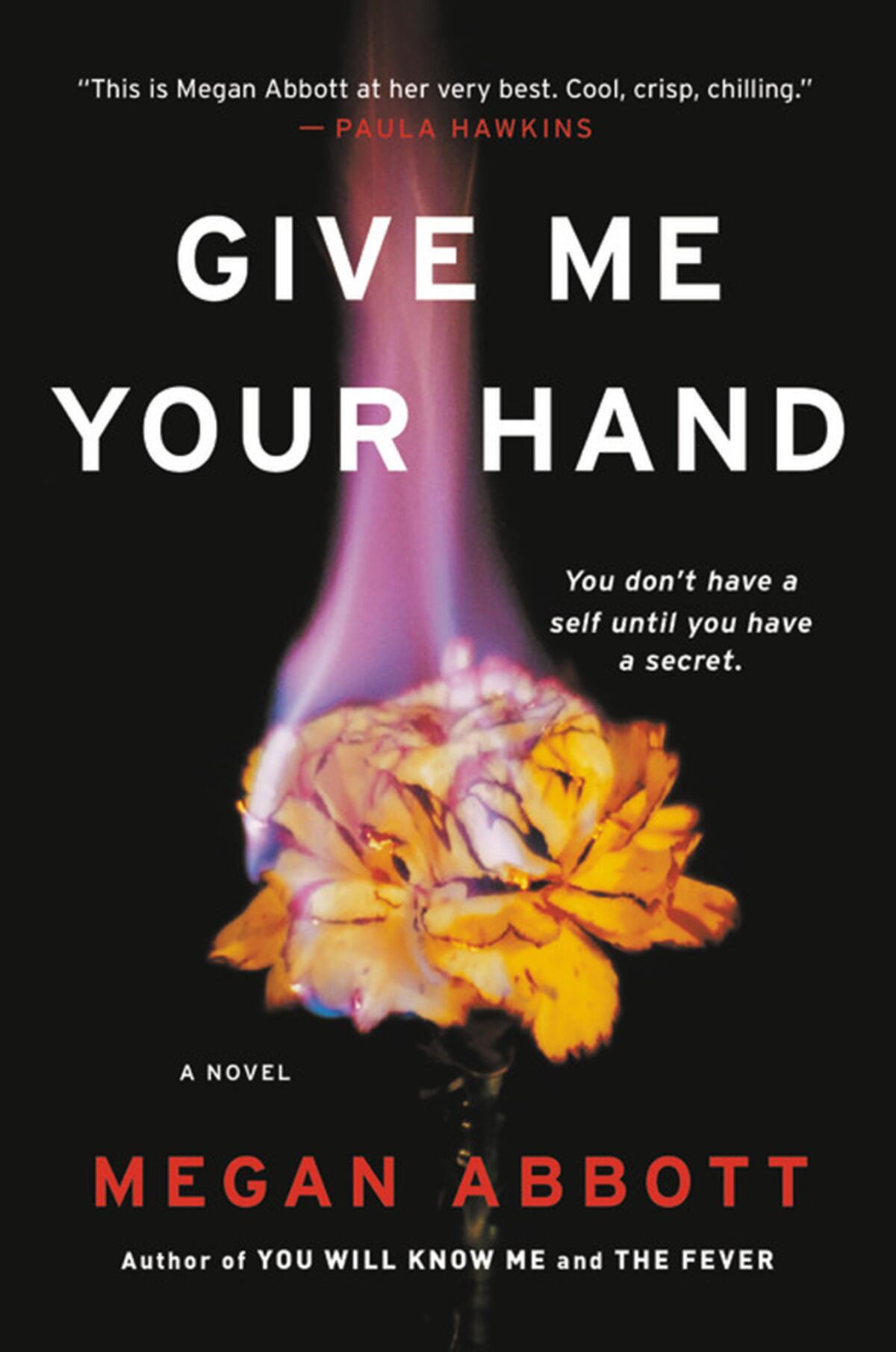

Megan Abbott on “Give Me Your Hand”

For someone who likes to kill people in her books, Megan Abbott is tremendously cheerful. Her conversation was peppered with laughter when I reached her by phone at home in Queens, N.Y., just having finished the book tour for her latest novel, “Give Me Your Hand.”

The book is the story about a lifelong rivalry/friendship between two female scientists, Kit and Diane, who find themselves competing for a coveted spot on Dr. Severin’s team studying premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). Told from Kit’s point of view, we see her life in the lab, where she’s ambitious and holding her own in a male-dominated space, as well as flashbacks to her teenage friendship with Diane. It’s safe to assume that someone ends up dead.

“When I start the parts that seem like they’re going to be fun are always really hard,” she said about writing. “Like the death scene, that scene took forever.”

We talked about her book and much more. Our conversation has been edited.

Tell me about how you found your way into the world of scientific research. I’m guessing that it’s not a parallel career for you.

No, it’s very unfamiliar to me. At a certain point I regretted choosing it [laughs] because it was so overwhelming and I didn’t know how to find a way in, it was so foreign. I had written quite a bit about sports and body competitions so I wanted to do something that was about a competition of the mind. I thought labs were such cinematic, spooky spaces. I talked to a few female scientists and their talk about the day-to-day life in the lab; how a male coworker had a messy lab bench, expect her to pick up after him, that kind of stuff. The fascinating lab dynamic, that really helped me. Then the workplace became more central.

Let’s talk about Dr. Severin. I pictured her as Susan Sontag dressed as Anna Wintour, but a science brainiac.

She emerged slowly. I hadn’t intended her to play such a large role. I remember, even at NYU [where Abbott got her PhD], there would be very cool professors that had this aura of glamour, people who would follow them around like acolytes. It was definitely inspired by that. The women would be like a Susan Sontag type, where there’s just this confidence — for women who are unsure of themselves like I was, you see that confidence in another woman, you see how you can do this. But also, because she is a woman, Dr. Severin is playing a little bit of a game too. She’s using her glamour and sexiness of her status to get something done that she thinks is really important.

Is PMDD real?

It is quite real. The stats are 3-8% of women suffer from it, but they actually think it’s much more, that it’s very underdiagnosed. The decisive factor is whether those features that one has in bad PMS — mood swings, crying, and not being able to get out of bed — in PMDD it’s when they interfere with your life. You can’t go to work, or you have trouble parenting. That’s how they diagnose it. Now they’ve found this biological piece that shows what these women suffer from; it’s the way their cells respond to progesterone and estrogen. So it is really real. But I think it’s so stigmatized; it’s a controversial term, accused of being an anti-feminist. It’s definitely had a contested history.

It’s so interesting the ways that science intersects with culture. Both Kit and Diane seem to hold onto science as a certainty in lives that they can’t control.

In some ways, that’s what drives them to science, this real discomfort, for Diane but for both of them really, discomfort with the wildness of emotion and all these primal urges. That they, for different reasons, would rather keep under control, because women have to be disciplined to advance in a way that men don’t. Women, like any minority in the workplace, you have to be 10 times better. I think that awareness, that the discipline is essential, you can’t allow your emotions to appear at all, you must wear this mask.

In some ways for Kit, it’s about class. She can’t control that she comes from a poor family. And science is a certainty where she can excel, but it takes all of that control.

There’s no room for error for both of them for different reasons. For Kit, it is an awareness that she has imposter syndrome. And also that she’s viewed this particular way. I had a long conversation with my editor about whether Long Island Iced Teas signified some kind of class thing. We were talking about it because there’s that scene where she drinks too many Long Island Iced Teas and —

— hooks up with an affluent coworker —

— and he assumes that she’s had many of them in her lifetime. Where I grew up, Long Island Iced Teas were considered kind of a trashy drink, you know? It was sort of a signifier. She’s aware that he’s aware — there’s a lot of unspoken subtexts that play into class and gender and sexuality.

There’s this incredible balance in the way that you’ve portrayed Kit. We’re on her side, but sometimes I lost being sympathetic with her.

That makes me happy to hear. Several people have told me that, including my English editor when she read it. Because I had to come at it from the other direction. I was trying to do this trick where you’re with Kit, Kit is closer to us, we all identify with her, then you start to respond to Diane. I was trying to have them, in some ways, almost flip places. I call this the Swearingen Effect, from “Deadwood.” The hero, Sheriff Bullock, and the bad guy Al Swearingen, they kind of swap places as the series goes on. I always kind of liked that — the good guys get kind of muddied, and the bad guys, you kind of start to love.

As someone who’s written nine novels and is now on staff of the HBO series “The Deuce,” are there other lessons that you’ve taken between books and TV?

One of the reasons that a lot of crime writers have moved to TV is story and pacing is essential — so that felt like a natural thing. But the other way is trickier; it is so different. Novels are so interior and idiosyncratic and such a solitary process. I think watching TV has influenced my books, but I don’t think writing TV has. I have become aware a little earlier of structural problems, because scripts are all about structure. I don’t normally write novels thinking about that; I make the structure in the revision, I kind of create it afterwards. Now I’m more aware of problems at the beginning.

Really? With this book I really thought you must have mapped everything out before you started writing. Is that not the case?

It’s not. I knew where I wanted it to end, mostly. Though that changed too.I had a realization halfway through that I was going to drop the past out for a long section of the book. For a long time you’re toggling between the two time periods, and then the past disappears, and I thought, am I allowed to do this? It seemed like I was cheating in some way, but then I did it [laughs]. The end did change a bit; I did finish it right after the election and it became bigger, darker, more operatic — that’s what i was feeling at the time.

I think it was big and operatic and that was one of the things I liked about it. Because it was somewhat unexpected.

If you’re looking for a traditional plot twist, it’s not really a plot twist so much as a character twist, I suppose. Kit and Diane would both become more and more complicated, and their relationship with each other would become more and more complicated. They’re not really friends, they’re not really enemies — what are they? What is this thing? Someone at a book event, we were talking about how when someone tells you their secret, they keep you hostage, and in some way I do think they’re each others’ hostages. I think a lot of female relationships are like that.

Do men not have that?

I’m sure some do. I think women have it even more. The things that women might tell each other that they don’t say elsewhere; the ways that women bite their tongue so much in the workplace. There’s all these places where your gender becomes an issue. All these discussions of complicity we’re having now — so much of it is about the things we weren’t saying, the secrets that we were all hiding.

You’re referencing #metoo and accusations of workplace sexual harassment. Earlier you mentioned feeling dark after the election. Are you talking about the political sphere, or the workplace, or both?

I guess they’re all so connected now. It definitely does feel to me like the election and #metoo are forever linked. The election was a surprise to a lot of people to significant degrees; it was certainly disruptive, no matter where you land. And now things can’t be the same. We can’t go back to the way it was. Seems like there’s less of a willingness to accept it, and I think that’s really interesting — in the workplace, in one’s own relationships, and at the national level. We’re all doing that review of things that happened to us, or things that we heard about and didn’t do anything about, doing that life review in all these areas too.

Do you see that as being something that can be fodder for fiction?

I don’t think I could write a book that had an ideological plan going in — I think that would be a terrible book. At least for me. I hear people can do that, or write in a satirical bent — but my books are pretty earnest and they don’t come from an ideological place. It’s in there, I’m sure, because you have opinions and feelings. But the books tend to come from more murkier ground, for me.

You also have a PhD in English and American literature. What was that about?

My dissertation was on hard-boiled fiction and film noir, the American studies bent to it. When you‘re writing crime fiction, especially if you like the history of it, the people you admire tend to be the big boys [laughs]. So they were always my inspiration. I really started writing because of Chandler and Hammett and Cain, the greats of the hard-boiled noir era. And I love James Ellroy, he was a huge, huge influence on me.

When I defended my PhD and I had two or three male professors and one female professor, and the female professor ended up pouring the water for everyone and she looked at me and she said, “note this” [laughs]. She was a rising professor in her field and somehow everyone had to wait for her to pour the water because she was a woman.

In the book, Dr. Severin is trying to mentor these young female scientists. Have you had similar experiences?

I tend to get a lot of books sent to me, debut female crime novelists, I try to read a lot of them. Laura Lippman helped me a lot when I was coming up, people like Sarah Paretsky were always really supportive of debut novelists. So I always tried to follow their model. Kind of a warm, inclusive community, and I want to keep that alive.

Can we talk about the dichotomy of people who like killing people in fiction and being warm and inclusive in real life?

[Laughs] That is so strange. I talk to literary novelists about this all the time, because they are sort of mystified by how nice crime novelists are, and how we like each other. I guess the easy version is you get it out on the page, right? So you don’t have to carry those negative feelings with you. It’s probably not that simple. I guess, in crime fiction, we’ve always been sort of considered a little lesser, you know, or whatever. We sort of celebrate that, there’s some joy in that. But I’m sure there’s some really dark and twisted crime writers, I just don’t know them. Or they’re really good at hiding it.

Kellogg is The Times’ Books editor.

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.