We are bearing witness to a profound moment in black culture, Aperture shows

Even as we see images of what most of us already know — that police violence against black people in America is occurring with vicious regularity — something remarkable is materializing in its wake. For all the pain, anxiety and devastation caused by the widely circulated video footage of black lives being literally extinguished, we are also bearing witness to a pronounced moment of black cultural ascension.

Three young black women start a social media revolution with the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter that spreads nationally after Michael Brown was fatally shot by police in Ferguson, Mo. Ta-Nehisi Coates wins a prestigious MacArthur “genius” fellowship, reinforcing his position as our leading public intellectual. Protests by students on college campuses over racial issues lead to resignations and administrative change; Bree Newsome scales a pole to remove the Confederate flag in South Carolina; Amandla Stenberg’s video primer about cultural appropriation, “Don’t Cash Crop My Cornrows,” goes viral; major media outlets across the country dedicate significant coverage and think-piece space to Beyoncé’s “surprise” visual album “Lemonade.” What a time.

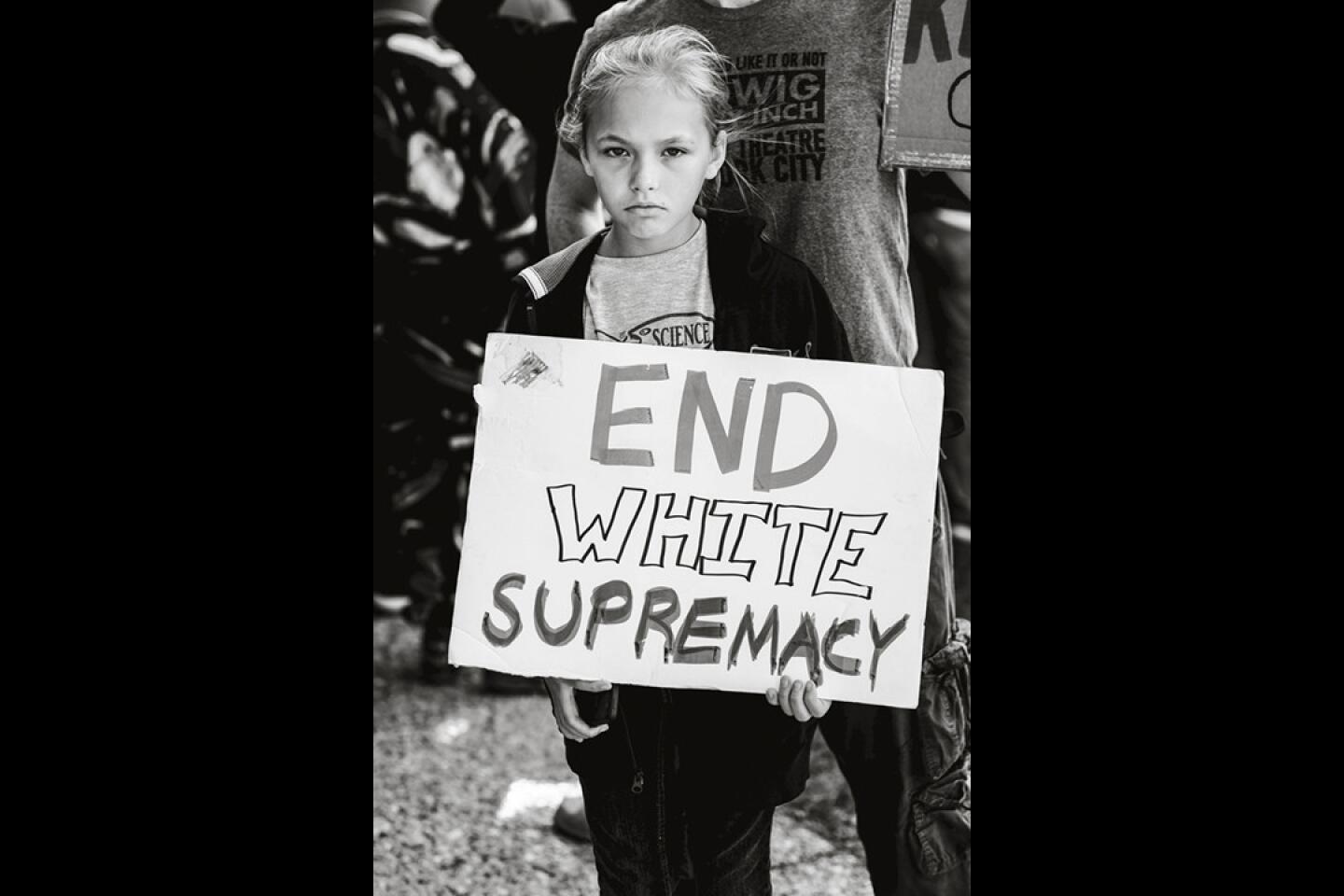

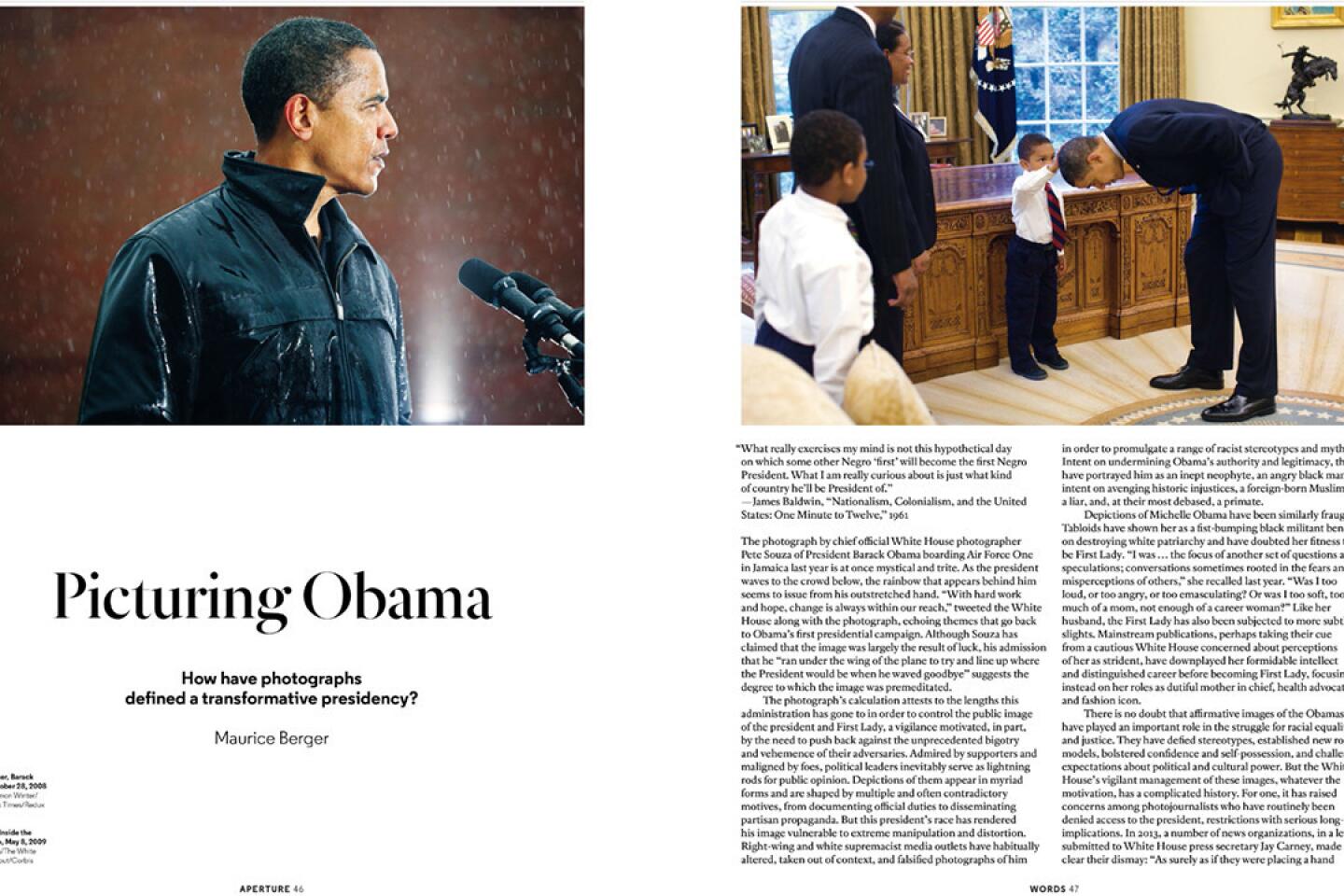

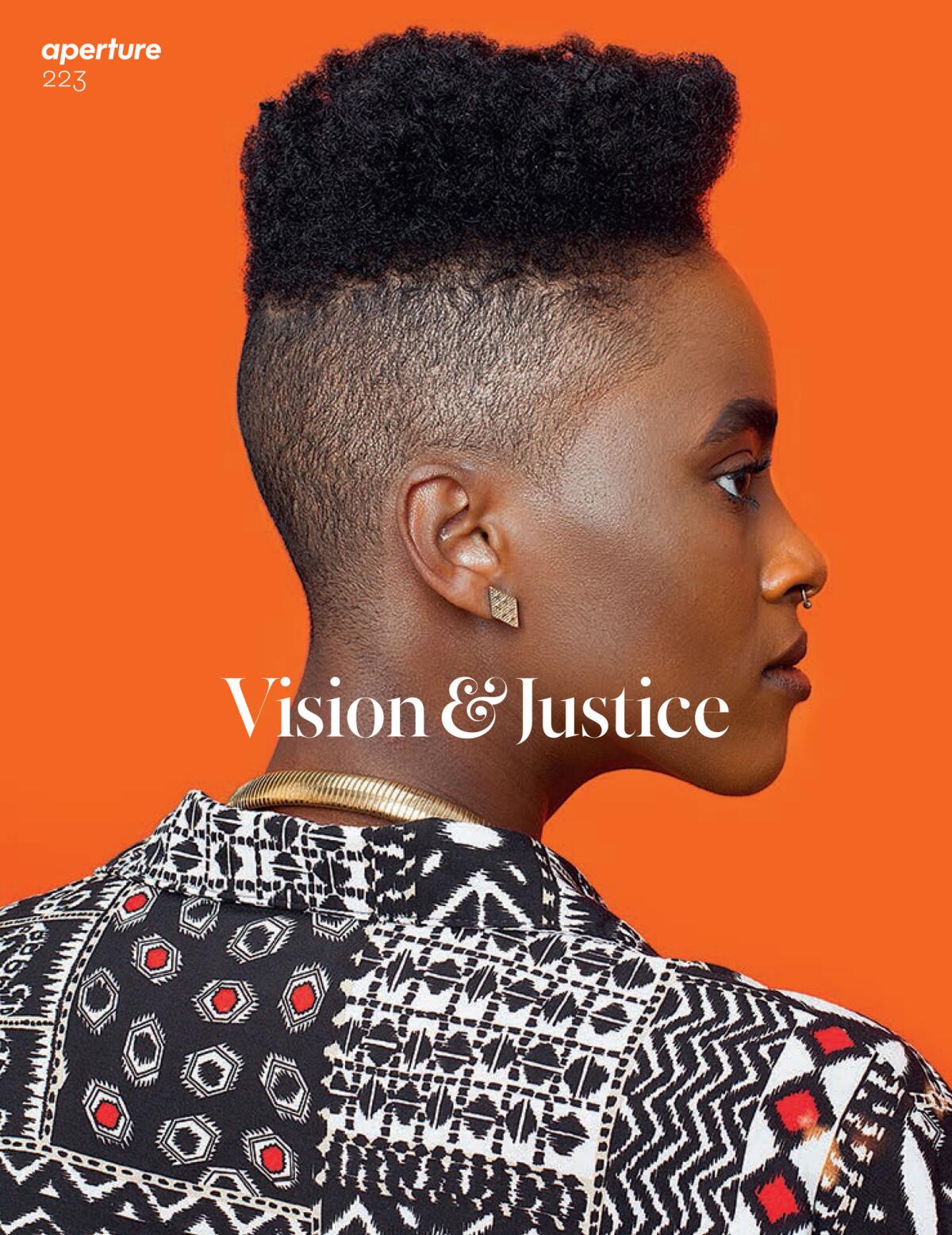

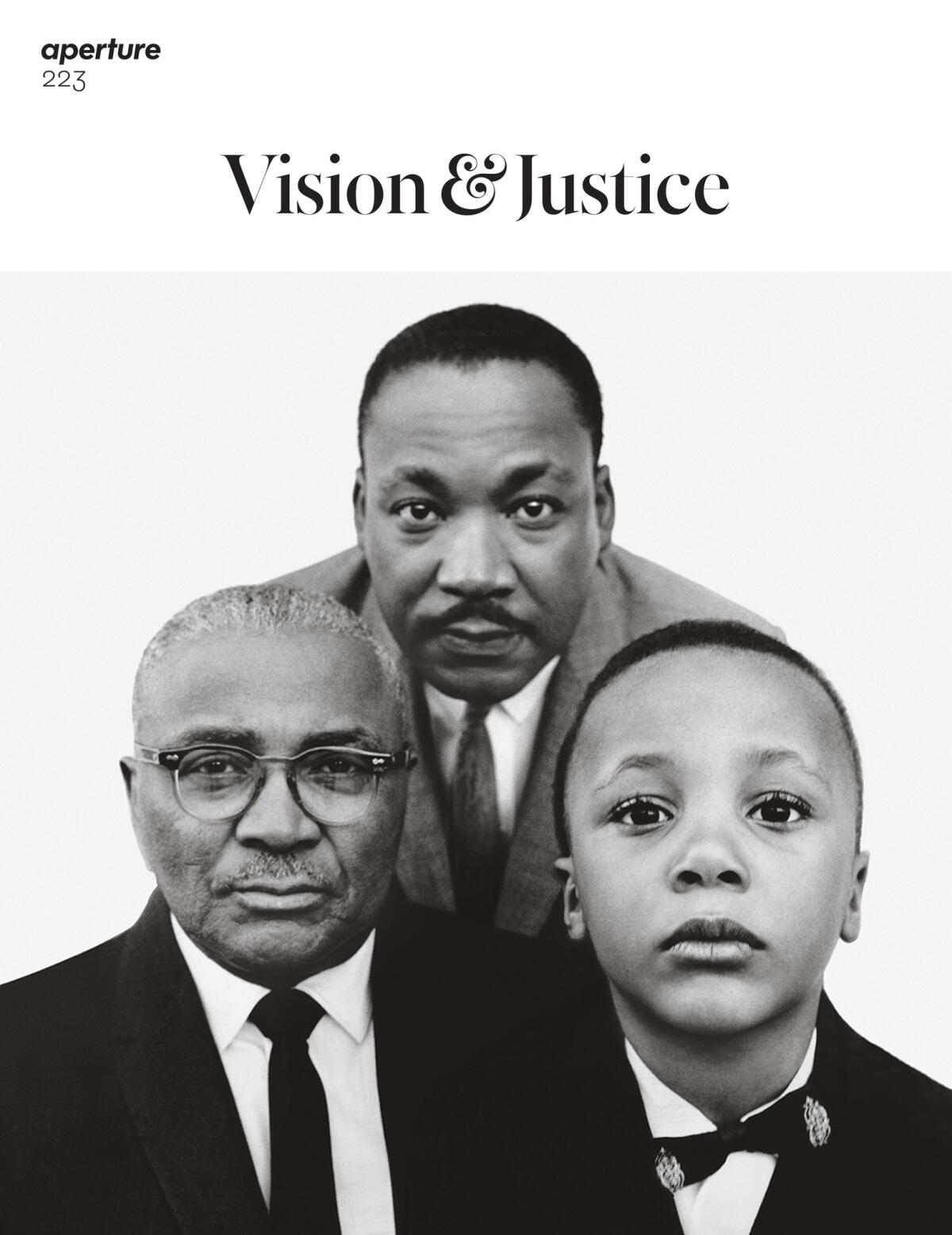

Indeed, enter Aperture magazine, right on point with a radically stunning special summer issue aptly titled, “Vision & Justice.” The 54-year-old photography magazine, which also operates as a multiplatform publisher and foundation in New York City, delivers on this zeitgeist with a robust, 152-page edition guest-edited by Sarah Lewis. “American citizenship has long been a project of vision and justice,” she writes in her preface. “Understanding the relationship of race and the quest for full citizenship in this country requires an advanced state of visual literacy, particularly during periods of turmoil.”

In her framing of the collaborative work and commentary spread throughout the issue, Lewis draws from both history — the concept was inspired by abolitionist Frederick Douglass and his Civil War speech “Pictures and Progress” — and the present, noting the heightened visibility of racial injustices captured and disseminated on various forms of social media, such as Instagram, where the young photographer Devin Allen chronicled the unrest in Baltimore after Freddy Gray died in police custody. Lewis, who is assistant professor of history of art and architecture and African American Studies at Harvard University, assembled a magnificent lineup of creatives and writers to reflect on “what aesthetic force can do” as seen in the equally spectacular range of images by photographers and artists.

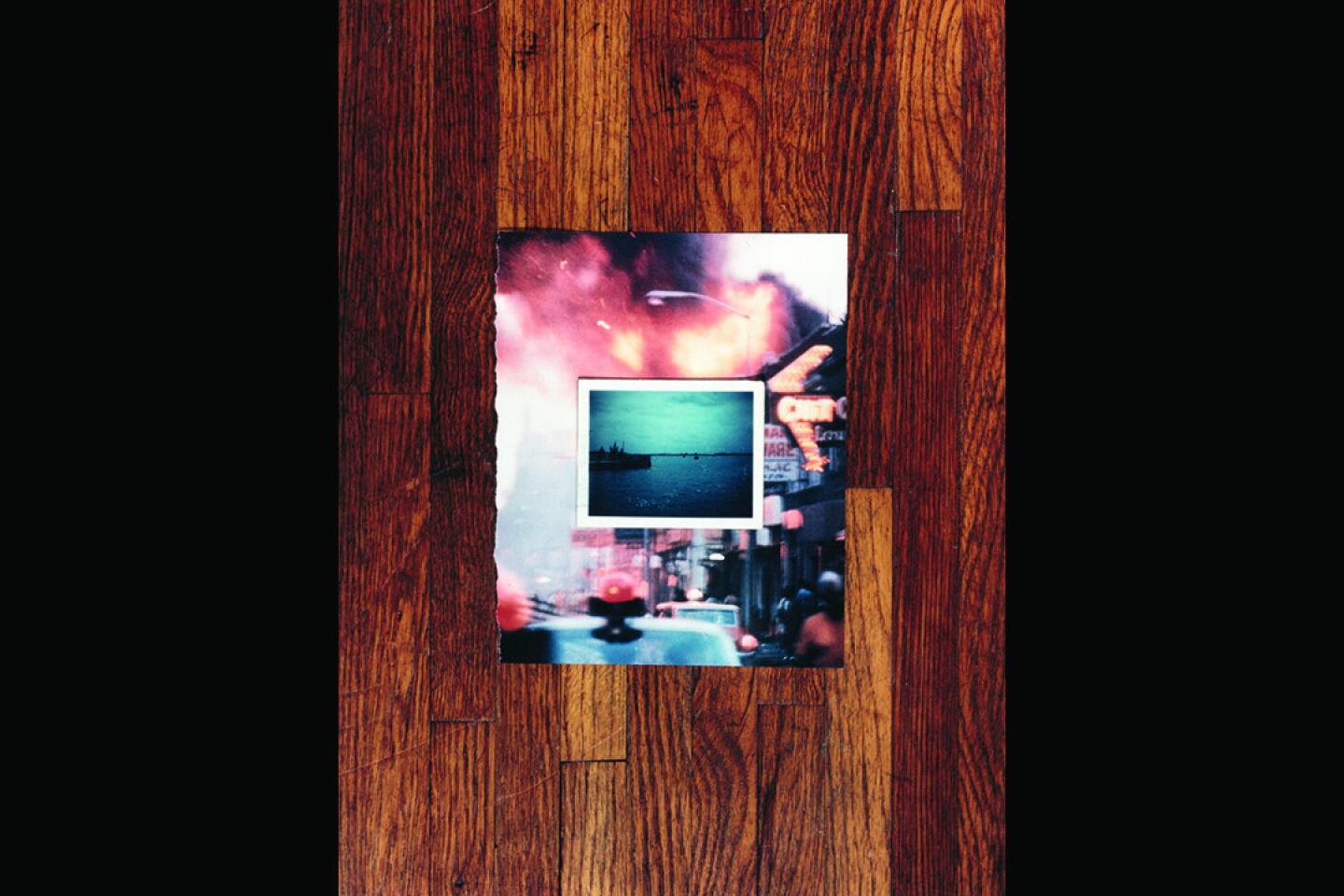

Musician Wynton Marsalis and opera singer Alicia Hall Moran discuss favorite photographs in their personal collections — Frank Stewart’s “Calling the Indians Out,” an image of black folks gathered on a city street banging on tambourines, evoking the ancestors and preparing for “the Big Chief on Mardi Gras Day,” and Ficre Ghebreyesus’s “Liberation Day, Asmara,” respectively. The musicians, both art collectors, talk about their photos with a gracious intimacy, a delicate possessiveness: “It’s the photo of our hearth,” writes Moran, who received the print as a personal gift from Ghebreyesus.

Conceptual photographer and multimedia artist Hank Willis Thomas, known for his series “Unbranded: Reflections in Black Corporate America, 1968-2008,” and the ongoing transmedia project “Question Bridge: Black Males in America,” riffs on his favorite things, including the seminal book “Reflections in Black: A History of Black Photographers, 1840 to the Present” (2000) by his mother, illustrious photographer Deborah Willis, who is also featured in this issue.

There is a substantive conversation between filmmaker Ava DuVernay and cinematographer Bradford Young; the two discuss their working relationship on the film “Selma,” black images on the big screen, and navigating what DuVernay calls “cinema segregation,” in which black folks in certain communities across the country aren’t able to go see the few Hollywood films made by and about black folks because there are no movie theaters where they live. It’s a tricky disconnect to reconcile, as media outlets, apps and platforms continue to provide easy access to real-life images in which black lives are discarded, devalued, destroyed — anyone with an iPhone or a TV could (and can still) watch the dash-cam video footage of Chicago police shooting 17-year-old Laquan McDonald 16 times until he crumples down dead in the street.

Some of the pairings between artist and writer are more conceptual, if still palpable. Reflections on the visual narrative of Carrie Mae Weems’ iconic “Kitchen Table Series” include an elegant, blistering meditation from playwright Katori Hall, recalling the days when her mother took a hot comb to her head near the sensitive hairs at the nape of her neck known among black folks as “the kitchen.” “As barbaric as this nighttime ritual of singed hair may seem to some, it is the tenderness served up to us tender headed that has left its indelible mark. The kitchen is a place to be burned, but it is a space to be healed as well.”

Acclaimed poet Claudia Rankine writes with marked insight on the work of Nigerian artist Toyin Ojih Odutola: “Blackness, for her, is not only her subject; it is also her question. The space of blackness is itself the subject of her portraits.” Odutola’s drawings are less easily defined than some of the other work represented in the edition — hers is more like illustrated math, with its colorful compound properties, bold symbols and graphite measurements.

Other noteworthy contributions include novelist Teju Cole on photographer LaToya Ruby Frazier, a 2015 MacArthur “genius” fellow, and Harvard professor Khalil Gibran Muhammad on the rich history and regal subjects in Jamel Shabazz’s photography.

Cultural critic Margo Jefferson, whose book “Negroland” won the National Book Critics Circle Award for memoir in March, describes Lorna Simpson’s colorful, dazzling collages so vividly, you can almost see them: “Above each woman is a sumptuous yet ethereal design: her hair has become a headpiece of swirls and strands, feathery, filigreed, biomorphic, multihued.” Turn the page and there they are in their full glory. Jefferson has effectively rendered a seeable preface to Simpson’s work through the precision of her prose, and her willingness to not simply write about the art but to participate in it.

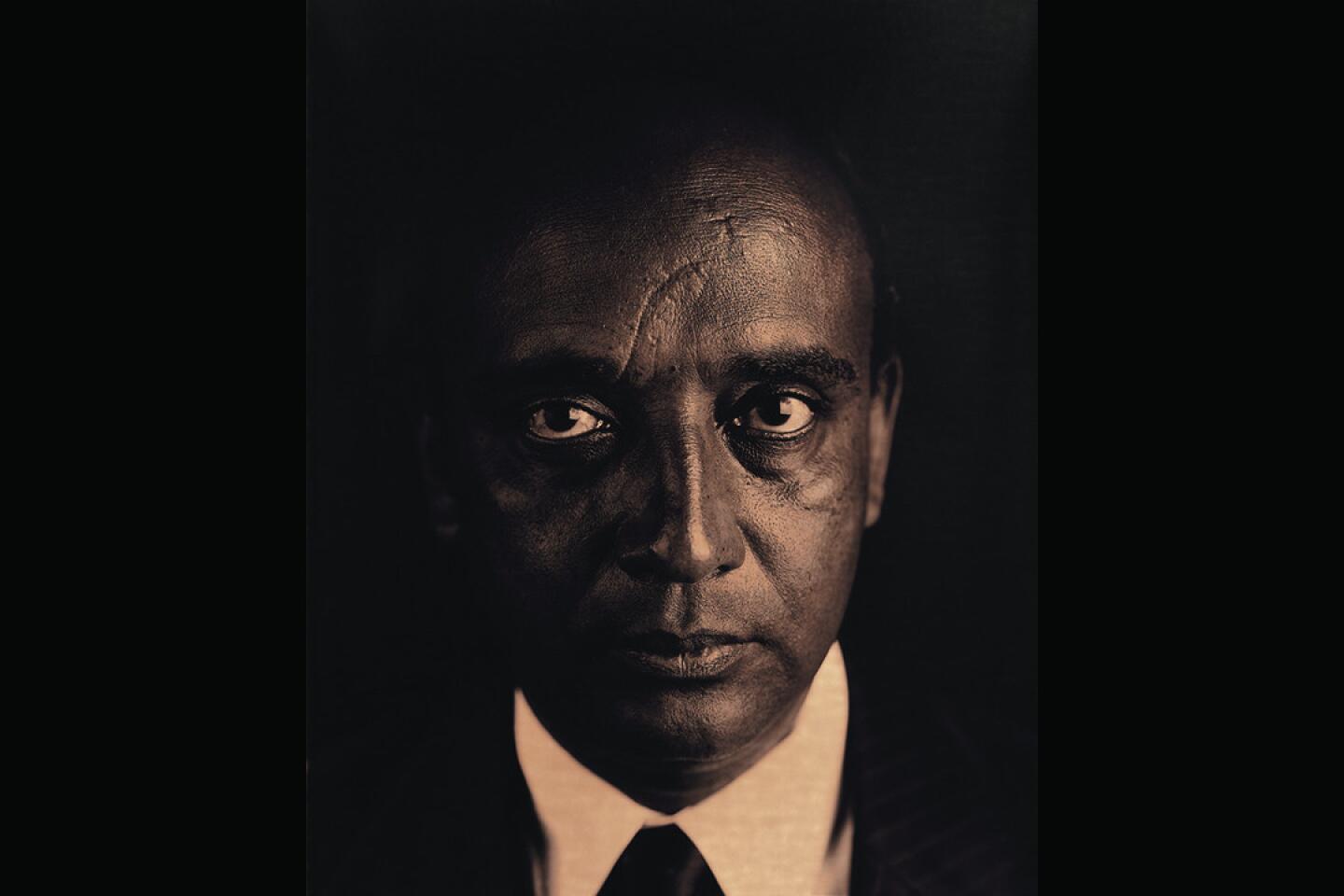

But the section that stood out for me the most was a conversation with the Ethiopian filmmaker Haile Gerima (excerpted from the literary journal Callaloo). Gerima, who emigrated to the United States in 1967, is best known for his 1993 film “Sankofa,” which combines African storytelling and symbolism with magical realism to create a beautifully abrupt aria of slavery and its rupturing of both the mind and the body. In response to a question about how his “deeply troubled characters ultimately gain some form of self-possession,” Gerima speaks with arresting clarity: “First, in general, just even the idea of storytelling — the aesthetics, the accent, and the structure of storytelling still has to operate in the empire of this Eurocentric America. America is really European aesthetics. In general, the vocabulary of America is a white supremacist vocabulary and Europe lives in America with all of us being the ambassador and emissary of its vocabulary. My struggle is not only what I want to tell, but it is the very form of storytelling that I am in constant struggle with.”

I grew up around very few black women; to me the books by Toni Morrison, Maya Angelou and Audre Lorde provided a vital link to a cavalcade of black mothers, grandmothers, sisters and girlfriends, which in turn inspired my first book, 1994’s “I Know What the Red Clay Looks Like: The Voice and Vision of Black Women Writers.” Like Gerima, I was then, and am now, engaged in constant struggle with what I want to tell and how I want to tell it — specifically regarding race — against a seemingly endless backdrop of presumed black inadequacy and foundational white supremacy.

Yet here we are, as black artists and writers, pushing forward in that struggle, which has always been long and arduous — showing up, turnt up, and getting into formation. We are engaged in a critical, culturally vigorous deconstruction of the perceived black monolith, and the white gaze that perpetuates it. It is, essentially, the equivalence of a national collective clapback — with vision and for justice.

Carroll, a writer based in New York, is one of our Critics at Large.

READ MORE:

MORE:

Meet Lisa Lucas, the bookish extrovert heading the National Book Foundation

Supreme Court rules that prosecutors intentionally kept black people off jury

Black Lives Matter activists criticize arrests of LAPD critics at Police Commission meetings

Authors Viet Thanh Nguyen and Maxine Hong Kingston dish on war and peace

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.