In a rare interview, Elena Ferrante describes the writing process behind the Neapolitan novels

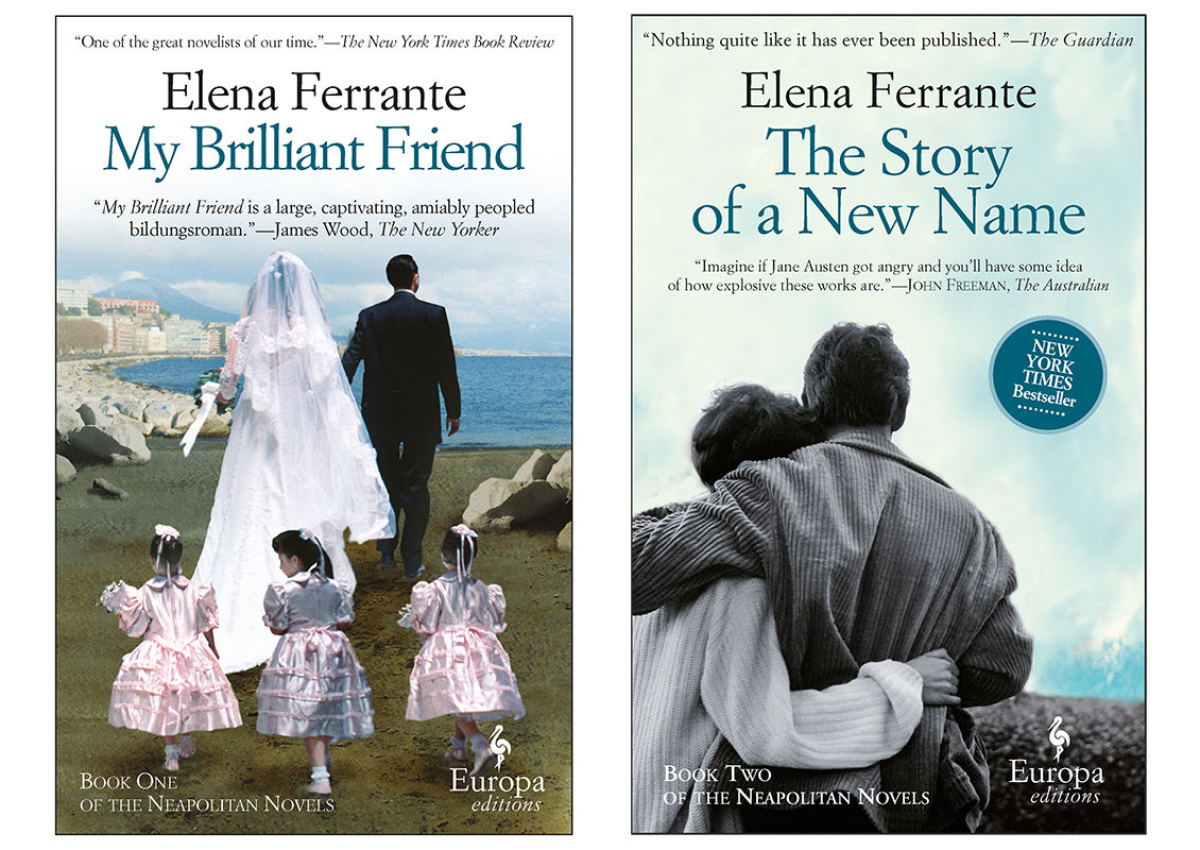

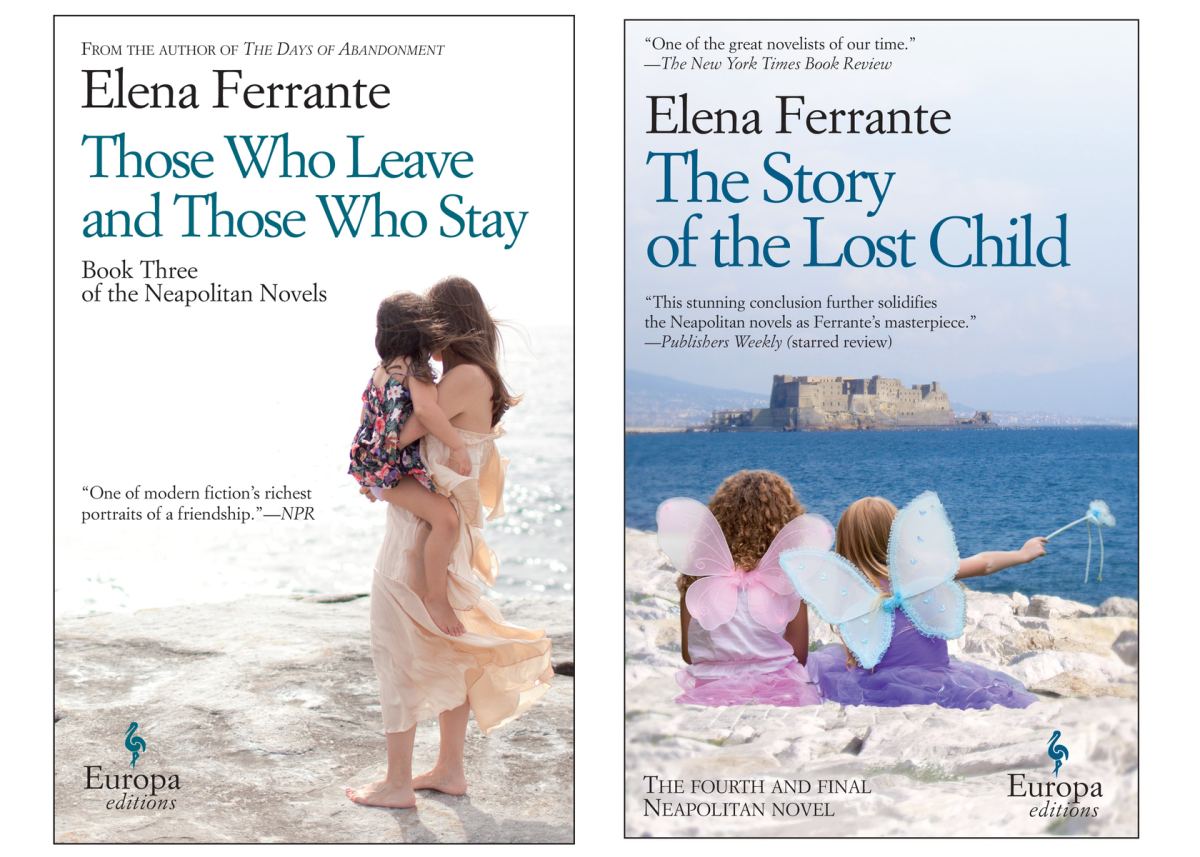

Seven years ago, it took just one book for an as-yet-unknown Italian novelist to become one of the most prominent personalities of the early 21st century. What made the phenomenon even more unheard of was that it involved an author who had written an epic with undeniable literary ambitions, not a book for young readers, like the “Harry Potter” series. It was a saga with numerous allusions to Italian history, anchored by geography to a small corner of Naples, and these facts seemed to condemn in advance its success as an export.

But the triumph of “My Brilliant Friend” is also stupefying because its author does no promotion at all. Elena Ferrante is a woman without a face, whose identity is known only to her Italian publisher, E/O. Her name is a pseudonym, its sound a discreet homage to the great Italian novelist Elsa Morante, author of “Arturo’s Island” — whose work, Ferrante says here, she has always appreciated. No one has ever succeeded in revealing Ferrante’s true identity, although certain names have circulated in the press: Domenico Starnone, a Neapolitan screenwriter and novelist, and winner of the Strega Prize in 2001; or Anita Raja, a Roman translator. Nearly two years ago, Italian journalist Claudio Gatti published a scoop, identifying Raja as Ferrante, after having scoured her tax returns and deciding that her assets exceeded that of the average income of a person in her profession. Against all odds, the supposed revelation of the identity of Ferrante provoked a worldwide scandal.

For her readers, Ferrante must be allowed to remain anonymous, should she wish to be. An international outcry rose up, from enraged readers who sought to protect the writer they love, and whose anonymity they wish to preserve. Nothing of the like had ever been seen before.

The series that begins with “My Brilliant Friend” has sold more than 5.5 million copies in 42 countries, with more than 2 million copies sold in the U.S. Published in America by Europa Editions, the books are the successful result of an editorial policy that favors demanding work and patience over instant gratification. For literary professionals, it is a sign that in a time of faint-heartedness, there is still another path to follow: Rather than publishing feel-good books for silly entitled people, you can reach a wide audience betting on real literature.

Where does the great enthusiasm for the tumultuous portrait of Lila and Elena (also called Lenù), the products of an underprivileged neighborhood of Naples, whose friendship begins in the late 1950s, come from? Aside from the thirst for long narratives, which we also see in the incredible boom in TV series, readers of the world seem to want to read about genuine feelings. Who among us has not dreamed of living the complex and spellbinding relationship of these “brilliant” friends? Lila gives up her studies to work in the family shoe factory, while Elena decides to receive a classical education and ends up leaving Naples to seek her professional fortune elsewhere. The proliferation of plot points and the multitude of characters, at a time when the hallmark is simplicity, is a further enticement. The fact remains that the book is first and foremost a war machine: It seduces slowly and possesses a hitherto unseen power of attraction and that irresistible je ne sais quoi that makes an overnight success.

And Ferrante? Behind her mask, the novelist distills her public statements with the stinginess of a pharmacist. The interviews she has given may be counted on one hand, and they have been exclusively conducted via email, with her Italian publisher as intermediary. Her desire for anonymity is non-negotiable. For her, once a book has been finished, it must stand on its own. Breaking her near-constant silence here, she explains how she conceived “My Brilliant Friend” in secrecy. She confides the profound joy she gets from writing and speaks of the pleasure she feels in responding to the curiosity of her readers through the volumes she writes. Far from having shut herself in an ivory tower, she discusses #metoo and launches a stirring appeal for the enduring gains of feminism. She compares the experiences of the great Hollywood actresses to those of the poor women of Naples, in a particularly stirring defense. Finally, she gives some unprecedented clues that may help us understand not who she is, but something that all in all is the same: why she writes.

Do you recall when you first had the idea for “My Brilliant Friend”?

I can’t give you a precise answer. It may have had its origin in the death of a friend of mine, or in a crowded wedding celebration, or perhaps in the need to return to themes and images of an earlier book, “The Lost Daughter.” One never knows where a story comes from; it’s the product of a variety of suggestions that, together with others that you are not aware of and never will be, excite your mind.

Did you know from the beginning that the complete work would require four volumes?

No. In its first rough draft, the story of Lila and Lenù fit very easily into a single, substantial volume. Only when I began to work on that first text did I understand that there would be two, three, four volumes.

Was the whole story planned in advance before the actual writing started?

No, I never plan my stories. A detailed outline is enough for me to lose interest in the whole thing. Even a brief oral summary makes the desire to write what I have in mind vanish. I am one of those who begin to write knowing only a few essential features of the story they intend to tell. The rest they discover line by line.

The first book of the series was published [in Italy] in 2011, the last in 2014 — a short period of time for such an ambitious endeavor. Had you written most of the series before the publication of the first volume? Can you tell us about the timing of the writing/publication of the novel?

I started in 2009 and spent a year, more or less, completing the entire story, with its various turning points. Then I began to revise, and I discovered with great pleasure that from the first page, the text was expanding; it grew and grew, becoming more detailed. At the end of 2010, given the mass of pages that had accumulated merely for telling the story of the childhood and adolescence of Lila and Lenù, the publisher and I decided to publish it in several volumes.

I imagine that when the first novel of the series was published, you were able to write in tranquility. Then came the novel’s extraordinary success, which could have jeopardized your writing. How were you able to keep your work from being disrupted by that overwhelming success?

It was a completely new experience for me. As a child, I liked telling stories and finding effective words for the small audience of kids of my age who gathered around me. It was electrifying to sense their encouragement, to feel that my listeners wanted me to continue, to pick up the story again the next day, the next week. It was a thrilling endeavor and an exciting responsibility. I think I felt something similar between 2011 and 2014. Once I was cut off from the media clamor — which was possible thanks to the absence that I chose starting in 1990 — that childhood pleasure returned: of giving form to a story while an increasingly vast and attentive audience wants you to tell more and more. While readers were reading the first volume, I was refining and finishing the second; while readers were reading the second, I was refining and completing the third; and so on.

Looking back, how would you describe the writing process? Was it effortless and smooth from the start? Or, on the contrary, did you have moments of doubt? Did you go through many drafts, with a lot of cutting and editing?

In the past, I’ve had a lot of problems with writing. I’ve always written, ever since adolescence, but it was a struggle, and I was generally dissatisfied with the result. The consequence is that I’ve rarely been convinced that I should publish. In the case of this very long story, things went differently. The first draft rolled along without running into any obstacles: The pure pleasure of telling a story dominated. Also, the work that ensued in the following years was surprisingly easy, a kind of permanent party. The honing of the four volumes, their polishing for publication, was essentially faithful to the first rough drafts and at the same time expanded and complicated the material. No crisis, in other words, no doubts, very few cuts, few rewritings, a cascade of new inserts. In my mind, there remains the impression of a tidal wave, and when it’s gone, you’re happy that you’re still alive.

In a letter to Mario Martone, you said that any distraction could make writing seem unnecessary, pointing out the fragility of it all. However, no writer seems stronger than you are, and more capable of building a colossal work of fiction. Would you agree that this combination of fragility and strength is essential to your writing?

My greatest fear is of suddenly feeling that to devote so much of my life to writing is meaningless. It’s a sensation that I’ve felt very often, and I’m afraid that I will again. I need a lot of determination, a stubborn, passionate adherence to the page, not to feel the urgency of other things to do, a more active way of spending my life. So yes, I’m fragile. It’s all too easy for me to notice the other things and feel guilty. And so it’s pride that I need, more than strength. While I’m writing, I have to believe that it’s up to me to tell this or that story, and that it would be wrong to avoid it or not to complete it to the best of my abilities.

Where does the vital energy of your writing come from?

I don’t know if my writing has the energy you say it does. Of course, if that energy exists, it’s because either it finds no other outlets or, consciously or not, I’ve refused to give it other outlets. Of course, when I write, I draw on parts of myself, of my memory, that are agitated, fragmented, that make me uncomfortable. A story, in my view, is worth writing only if its core comes from there.

In your description, Naples is rough, violent and unpleasant, and even more so in the second half of the fourth volume, where Lila and Lenù have to confront violence on every side. Have you witnessed acts of extreme violence in Naples yourself? How have Neapolitans been able to cope with violence over the years, and have they developed a particular understanding of the violence innate in human beings, and do you perhaps share that?

One has to be very fortunate not to be touched even slightly by violence and its various manifestations in Naples. But perhaps that’s true of New York, London, Paris. Naples isn’t worse than other cities in Italy or in the world. I’ve spent a lot of time coming to an understanding of it. In the past, I used to think that only in Naples did the lawful continuously lose its boundaries and become confused with the unlawful, that only in Naples did good feelings suddenly, violently, without any break, become bad feelings. Today it seems to me that the whole world is Naples and that Naples has the merit of having always presented itself without a mask. Since it is a city by nature of astonishing beauty, the ugly — criminality, violence, corruption, connivance, the aggressive fear in which we live defenseless, the deterioration of democracy — stands out more clearly.

Lila and Lenù suffer a lot throughout the books. Why did you choose to subject them to so many tragic experiences of all kinds?

It doesn’t seem to me that their sufferings are very different from those which women endure every day in every part of the world, especially if they’re born poor. Lila and Lenù fall in love, marry, are betrayed, betray, search for a role in the world, face discrimination, give birth, raise children, are sometimes happy, sometimes unhappy, experience loss and death. I do use the novelistic, but relatively sparingly. The emotional bond we establish with characters is generally what makes their story seem like an endless series of misfortunes. In life, as in novels, we are aware of the pain of others, we feel their suffering, only when we learn to love them.

In the fourth volume, why did you choose to make Nino so cruel and superficial?

I wanted to describe the effects of superficiality when it’s combined with a good education and moderate intelligence. Nino is a smart but superficial man, a type of man I’m very familiar with.

Why did the narrative require the traumatic and nightmarish disappearance of Tina, in the fourth volume, near the end of the story?

Here I will decline to give you my reasons — I prefer that readers find their own way. I can only emphasize that that event was always, even before I began to write, one of the few definite and inevitable stops on the narrative journey that I had in mind.

In life, as in novels, we are aware of the pain of others. We feel their suffering only when we learn to love them.

— Elena Ferrante

Lila is enthusiastic about new electronic tools, like PC computers. She seems to be driven by an instinctual brilliance, and yet, surprisingly, she understands these logical machines. Is she more unpredictable than Lenù, or is it the other way around?

Lila, in my intentions, is never enthusiastic. She applies her intelligence to whatever, for one reason or another, comes into the field of action that she herself is given, starting from the moment she is forced to leave school. It’s because her father is a shoemaker that she designs shoes. It’s because Enzo is taking correspondence courses from IBM that she becomes involved with electronics. Unlike Lenù, who uses education to force the boundaries of the neighborhood and escape, eagerly aspiring to write, Lila acts brilliantly on what turns up, without using up her own capacities in any of the things she happens to get involved in. If one wanted to put it schematically, the only long-range project that really excites Lila is the life of her friend.

In the book, women struggle. Men often take advantage of them. How do you feel about the #MeToo protests throughout the world?

I believe that they have put a spotlight on what women have always known and have always been more or less silent about. Patriarchal domination, even — despite appearances — in the West, is still very entrenched, and each of us, in the most diverse places, in the most varied forms, suffers the humiliation of being a silent victim or a fearful accomplice or a reluctant rebel or even a diligent accuser of victims rather than of the rapists. Paradoxically, I don’t feel that there are great differences between the women of the Neapolitan neighborhood whose story I told and Hollywood actresses or the educated, refined women who work at the highest levels of our socioeconomic system. And raising one’s voice, saying, “Me too,” seems a good thing, but only if we maintain a sense of proportion: Just causes in particular are damaged by excesses. Even though the power of [offenders] large and small at the center of the world or on its peripheries lies in not being ashamed of the various forms of rape they subject us to and, by means of a repulsive stratagem, in making us think that it is we who should be ashamed.

Would you predict — and would you call for — a new feminism to emerge from #MeToo?

A certain disdain for the feminism of mothers and grandmothers has spread among the younger generations in recent years. There is a conviction that the few rights we have are a fact of nature and not the product of an extremely hard cultural and political battle. I hope that things change and that girls will realize that we have millenniums of subservience behind us, that the struggle should continue and that if we lower our guard, it won’t take much to eliminate what, at least on paper, four generations of women have with great difficulty gained.

Would you agree that your novel belongs to a tradition of popular narratives (such as those of Alexandre Dumas), with a lot of action and characters, rather than to a modernist, more minimalist approach to storytelling?

No. I can decide to reuse some of the powerful devices of popular literature, but I do so, like it or not, in an era completely different from the one in which that literature performed its task. I mean that with some regret, I can in no way be Dumas. To draw on the great tradition of the popular novel doesn’t mean creating, for better or for worse, that type of narrative but rather using it, distorting it, violating its rules, disappointing its expectations, all in the service of a story of our time. Rummaging in the great historical warehouse of the novel and the anti-novel is today, in my opinion, a duty for anyone who is by profession a narrator. Diderot could write “The Nun” but also “Jacques the Fatalist.” We can erase the boundary between literary experiences that are different from one another and use them both, at the same time, to give a shape to this historical moment. A lot of action, many characters or the minimalism you allude to, taken separately, don’t carry us far today. Let’s try to get out of useless cages.

You once said that you discovered Flaubert when you were quite young, in Naples. When did you first fall in love with a book, or with a character, and also with literature?

Yes, I really loved “Madame Bovary.” As I girl, when I read, I dragged the stories and the characters into the world I lived in, and “Emma,” I don’t know why, seemed close to many of the women in my family. But long before “Madame Bovary,” I loved “Little Women,” I loved Jo. That book is at the origin of my love for writing.

Have you been influenced by women writers (possibly French, like Colette, Duras, etc.)?

As a girl, I read all kinds of things, in no particular order, and I didn’t pay attention to the names of the authors — whether they were male or female didn’t interest me. I was enthralled by [the characters] Moll Flanders, by the Marquise de Merteuil, by Elizabeth Bennet, by Jane Eyre, by Anna Karenina, and I didn’t care about the sex of the writer. Later, in the late ’70s, I began to be interested in writing by women. If I stick with French writers, I read almost all of Marguerite Duras. But the book of hers that I’ve spent the most time with, studied most closely, is “The Ravishing of Lol V. Stein”; it’s her most complex book, but the one you can learn the most from.

How do you feel about female writing? Do you believe that the category exists — that there is female writing and male writing? For example, Elsa Morante versus Hemingway? As for your own style, would you say it’s a combination of both male and female?

Certainly, female writing exists, but mainly because even writing is powerfully conditioned by the historical-cultural construction that is gender. That said, gender has an increasingly wide mesh, its rules have been relaxed, and it is more and more difficult to reconstruct what has influenced and formed us as writers. For example, I learned from the books I loved and studied, by male and female authors, and I could easily name them, but I’ve also been deeply affected by sentences whose provenance I no longer remember, whether it was male or female. The literary apprentice, in short, passes through channels that are hard to identify. So I would avoid saying that I was formed by this or that author. Above all, I would avoid saying that I was formed essentially by women’s writing, even though I very much loved and still love “House of Liars,” by Elsa Morante. We are in a period of great change, and the presentation of gender is at risk of being not only unconvincing but not really valid.

Living is a permanent disruption for writing, but without it, writing is a frivolous squiggle on water.

When you read a book, what do you appreciate most?

Unexpected events, meaningful contradictions, sudden swerves in the language, in the psychology of the characters.

In the book, motherhood is an enemy of writing (Lenù is so busy bringing up her daughters that she can’t get the concentration she needs). In your own experience, how is it best to write? Alone? Seeing no one? Living a secluded life? Or, on the contrary, going out a lot, drawing inspiration from meeting people, possibly being in love?

When one is in love, one writes very well. And, in general, if someone does not have experience of life, what does he or she write about? Spending one’s time focused only on writing is the ambition of an adolescent, of a sad adolescent. Living is a permanent disruption for writing, but without it, writing is a frivolous squiggle on water. That said, life, when it has the force of a tidal wave, can devour the time for writing. Motherhood, in my experience, is certainly capable of sweeping away the need to write. Conceiving a child, bringing it into the world, raising it is a marvelous and painful experience that over a fairly long span of time — especially if you don’t have the money to buy the time and energy of other women — takes away space and meaning from all the rest. Naturally, if the need to write is strong, you sooner or later find an arrangement that leaves you some room. But that holds for all the fundamental experiences of life. They hit us, they overwhelm us, and then, if we don’t end up dead in a corner, we write.

Was it hard to wake up one day thinking, “The story of Lila and Lenù is over. I’m finished with it.” Like giving birth and suddenly feeling empty in some way?

The metaphor of birth applied to literary works has never seemed convincing to me. The metaphor of weaving seems more effective. Writing is one of the prostheses we have invented to empower our body. Writing is a skill, it’s a forcing of our natural limits, it requires long training to assimilate techniques, use them with increasing expertise and invent new ones, if we find we need them. Weaving says all this well. We work for months, for years, weaving a text, the best that we are capable of at the moment. And when it’s finished, it’s there, forever itself, while we change and will change, ready to try out other weaves.

Have you possibly considered writing a sequel, or side stories (the way J.K. Rowling did with Harry Potter)? The ending does allow it, doesn’t it?

No, the story of Lila and Lenù is over. But I know other stories and hope I’ll be able to write them. As for publishing them, I don’t know.

Your novel values friendship more than anything else, even more than love, which is unpredictable and can vanish. Do you value friendship in that way, in your own life?

Yes, friendship has to do with love but is less at risk of being spoiled. It’s not constantly threatened by sexual practices, by the danger that exists in the mixture of feeling and the use of bodies to give and be given pleasure. Sexual friendship is more widespread today than in the past, a game of bodies and elective affinities that tries to keep at bay both the power of love and the rite of pure sex. But with what results I don’t know.

I have been asking many writers about where they write. The most recent was Tom Wolfe, describing his desk and the colors of his office walls — blue. Could you describe the place where you write (or, if not, can you tell us about some objects that you care about and which are around when you write)?

I write anywhere. I don’t have a room of my own. I know that I’d like a bare space, with white, empty walls. But it’s more an aestheticizing fantasy than a real necessity. When I write, if it’s really going well, I soon forget where I am.

This interview originally appeared in the French newsmagazine L’Obs in January 2018. Jacob is a L’Obs staff writer covering books and is the author of a nonfiction book "La guerre littéraire" (Héloïse d'Ormesson publishing).

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.