Why don’t iconic novels translate into film?

Earlier this week, I saw Michael Polish’s film adaptation of Jack Kerouac’s 1962 novel “Big Sur,” which opens Friday. The book is one of my favorites: dark, brooding, the flip side of the Beat road legend, a story of isolation and spiritual despair.

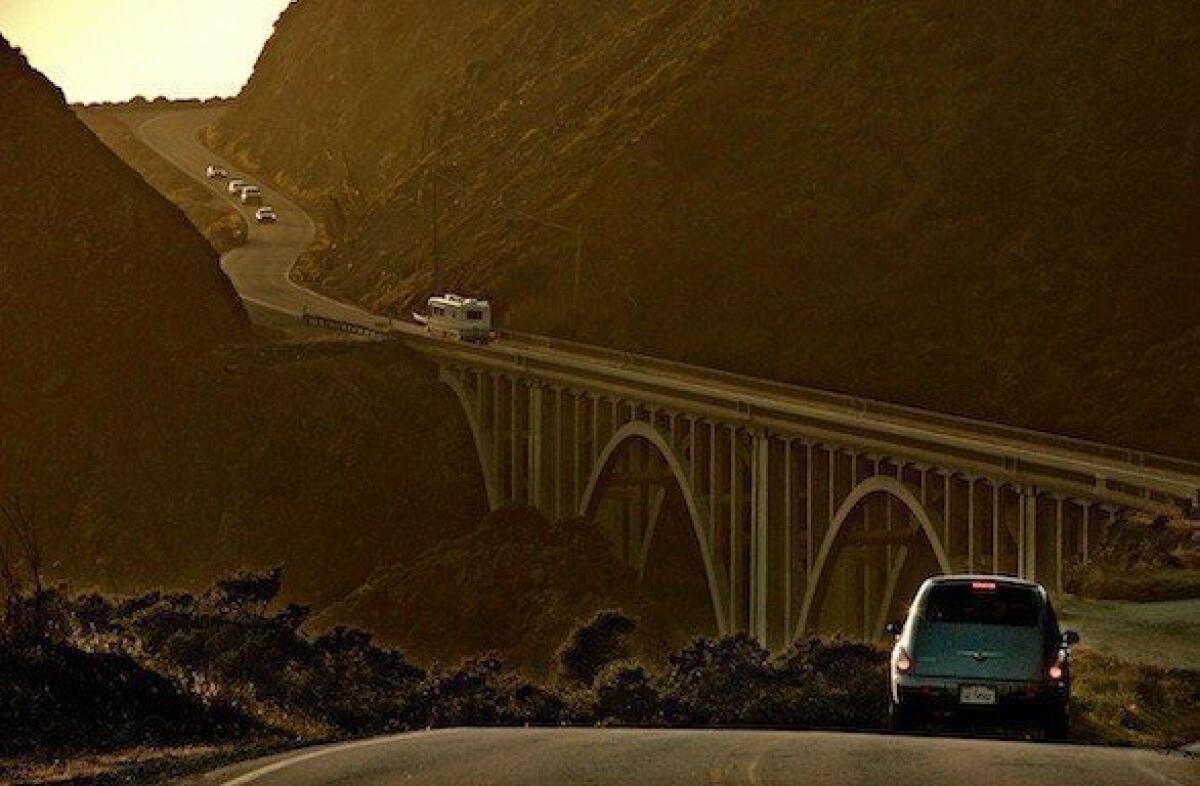

In it, we confront Kerouac’s alter ego, Jack Duluoz, as he tries to reconnect with himself at a quiet cabin in Bixby Canyon. But he is already too far gone in his dissolution (Kerouac died in 1969, at age 47, of an esophageal hemorrhage, what his biographer Gerald Nicosia described as a “classic drunkard’s death”) to find any solace, and so “Big Sur” traces a descent into madness made more vivid and moving by the fact that we know it is real.

This is one of the challenges of Polish’s adaptation, that it treats the story not as fiction but as autobiography. That’s always a tension when it comes to Kerouac, whose work was closely based on his own life. And yet, it seems important to remember that he was not a memoirist but a self-mythologizer, intent on using fiction, literature, to make sense of his life.

The film overlooks this, dispensing with the fictional frame and calling its characters by the names of those who inspired them (Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Neal and Carolyn Cassady). At the same time, it is — paradoxically — slavishly loyal to the language, if not quite the intent, of Kerouac’s novel, using long passages from the book as an ongoing interior monologue.

That works, at first; the first 20 minutes of the film are moody and atmospheric, setting up Duluoz/Kerouac’s dissatisfaction with celebrity, his sense of being unseen, misunderstood. Then, not unlike Walter Salle’s take on “On the Road,” which came out late last year, the movie craters, unable to get out from under the weight of its own heritage.

In “On the Road,” this led to an unfortunate hagiography, as Salle conflated the living of the story with the need to write the story, while leaving out the novel’s central theme, which has to do with the brutality of time.

Here, the problem is exactly opposite: In his desire to be faithful to Kerouac’s voice, his phrasing, Polish has neglected to give the film any life of its own. It’s beautiful, yes (how could it not be, shot up on the Central Coast), but ultimately static, a movie that gets lost in its despair.

This is a constant in Kerouac’s novel; Duluoz begins and ends in an equivalent state of desperation, which is one reason the story is so dark. But if that’s a gutsy move in fiction, to write a book in which there is no movement, just a deepening sense of desolation, the belief that there is (will never be) a way out of the cycle of self-doubt, of living, it doesn’t really work in film.

Why not? For one thing, film is not an interior medium, whereas, on the most essential level, interiority is all literature has. It’s what sets written narrative apart, the ability (requirement?) to excavate the interior, to get at the inner lives of characters defined as much by what they feel as what they do.

How to translate this into visual storytelling? “Big Sur” — as well as “On the Road” — suggests that the challenges of such a process may be insurmountable when it comes to a certain type of book.

Let’s call this type of book the iconic novel: a work of fiction driven less by action than by voice. “Under the Volcano,” “Last Exit to Brooklyn,” “Naked Lunch,” “Ask the Dust”: There’s a long line of such works that have failed as films, lacking both the depth and nuance that define them on the page.

I think of Baz Luhrmann’s adaptation of “The Great Gatsby,” a train wreck of a movie that fundamentally misreads its source material, then compounds the error by tacking on an unnecessary frame. It’s as if Luhrmann was saying that he didn’t trust Fitzgerald’s story, that there wasn’t enough pure narrative in it to make an effective film.

On the one hand, Luhrmann’s absolutely right about that: We read “The Great Gatsby” (or at least I do) not for the plot, which can be, in places, a bit thin, melodramatic, but for the language, the insights, the sheer power of seeing what Fitzgerald does on the page. It’s storytelling, in other words, rather than story that moves us, the how more than the what.

That’s true of movies also, although in a different sense, since we are always on the outside looking in. How, then, to evoke interiority, self-reflection? It’s this question “Big Sur” fails to answer … at least, in any way that resonates.

ALSO:

Missing the point on Jack Kerouac

Can Big Sur be successful as a film?

‘On the Road’ toward mortality: A critic ponders Jack Kerouac

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.