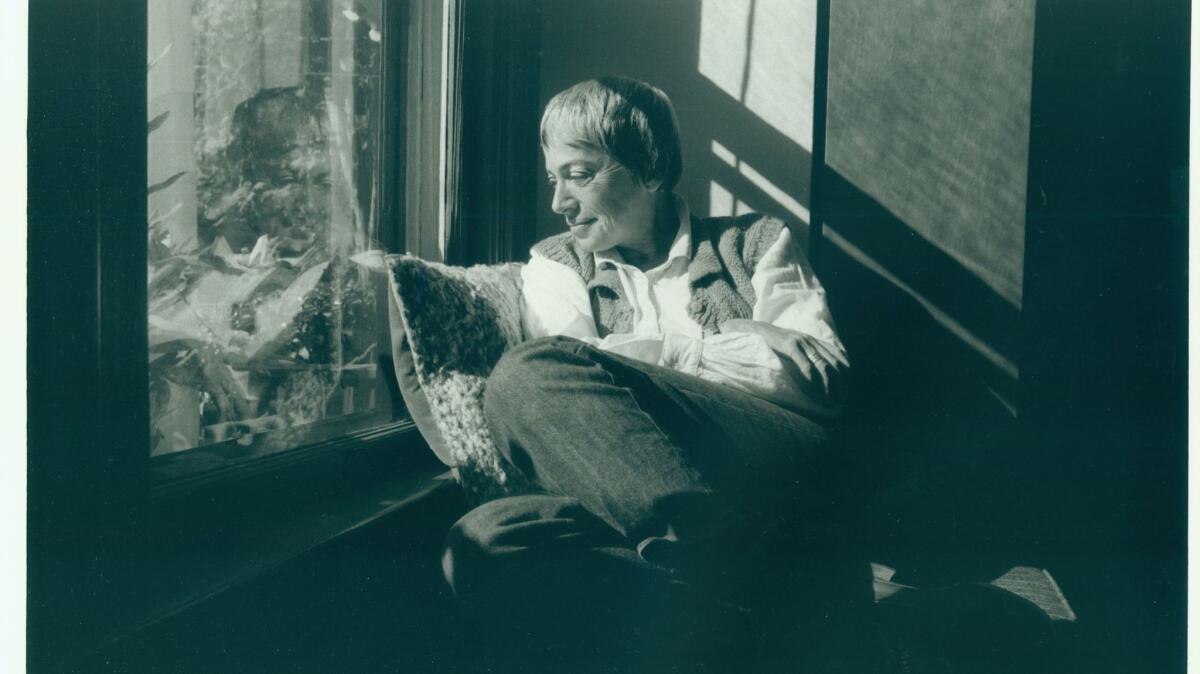

Ursula K. Le Guin, the spiritual mother of generations of writers; John Scalzi pays tribute

It’s less than an hour since the news broke that Ursula K. Le Guin has died and right now my Twitter feed, populated as it is with science fiction and fantasy writers, editors and fans, is a single, unbroken string of testimonials. N.K. Jemisin, who won back-to-back Hugo Awards for her novels “The Fifth Season” and “The Obelisk Gate,” is recounting how a note from Le Guin filled her with joy. Novelist Madeline Ashby recounts meeting Le Guin at a lecture, mentioning to Le Guin that she was writing her thesis on her, and Le Guin insisting Ashby send it to her. She did. Le Guin wrote back with notes.

Neil Gaiman is saying, “I miss her as a glorious funny prickly person, & I miss her as the deepest and smartest of the writers, too.” Patrick Nielsen Hayden, associate publisher of Tor Books, is saying, “She wasn’t always right, but she was always wise.”

On and on and on goes this immediate and real-time outpouring of grief and remembrance of a woman who gave us Earthsea, “The Left Hand of Darkness” and the short story “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas,” which is as much a parable for our time as anything that anyone has written, or likely will.

She was a supporting column of the genre, on equal footing and bearing equal weight to Verne or Wells or Heinlein or Bradbury. Losing her is like losing one of the great sequoias. As the unceasing flow of testimonials gives witness, nearly every lover and creator of science fiction and fantasy can give you a story of how Le Guin, through her words or presence, has illuminated their lives.

She was a supporting column of the genre. ... Losing her is like losing one of the great sequoias.

I am no exception. My story involves her book “Always Coming Home,” which posits the life of a people who, as Le Guin put it, “might be going to have lived a long, long time from now in Northern California,” when astounding technology exists but most people live simply in villages. In the book, a woman named Stone Telling recounts the story of her wanderings, and that story is interspersed with chapters featuring the songs and stories and rituals of this future nation, called the Kesh.

I met the book as a teenager, drawn to it by the cover, which featured an owl sailing over lush green fields. To that point, my reading in the science fiction and fantasy genre was largely of Heinlein and Asimov and other such authors, whose stories were brisk and straightforward and their futures clearly technological, where one chapter followed another and the plots unfolded at a punchy and professional clip.

So what to make of this book, which wasn’t particularly concerned with linear storytelling and more engaged with the gestalt of the created world, dwelling with the Kesh and with Stone Telling, staying a while with them rather than rushing from one plot point to the next?

What I made of it was what I think Le Guin intended: I stayed a while too. I dipped into the book from time to time and in no particular order, learning a little about the people she was writing about and the world at once familiar and alien to a California native. I can’t say I ever finished reading “Always Coming Home,” because I have never read it from start to finish. I’ve read all of it, yes. But not like I do most books. I kept coming back to it, a chapter here, a fable there. I was, in a real sense, always coming home to it. I still do.

This was a subtle gift that Le Guin gave to a young person wanting to be a writer — the idea that there was more to writing fiction than ticking off plot points, that a rewarding story can be told without overt conflict, and that a world wide and deep can be its own reward, for those building the world and those who then walk through it. “Always Coming Home” is not generally considered one of Le Guin’s great books, but for me as a writer and a reader, it was the right book at the right time. The book turned me on to the possibility of science fiction beyond mere adventure stories for boys — that the genre could contain, did contain, so much more. The book opened me to read the sort of science fiction I didn’t try before.

My own science fiction overtly owes more to writers like Heinlein than Le Guin, but you can find her in my work’s DNA if you look, in who I write about and the concerns I play out in my stories. I wouldn’t be who I am or where I am without Ursula K. Le Guin. Not too many years ago, I was given the opportunity to write an introduction to a new edition of “Always Coming Home,” in which I got to tell Le Guin just how important her book had been to me. I was glad to be able to tell her.

Look at the top tier of writers in science fiction and fantasy today — names like Jemisin and Gaiman and Jeff VanderMeer and Catherynne Valente, as well as rising stars like Bo Bolander and Amal El-Mohtar and Monica Byrne — and you see the unmistakable traces of Le Guin in their work. Multiple generations of her spiritual children, making the genre more humane and expansive, and better than it would have been without her. And all with stories of her.

I check back on my Twitter feed now, which continues to be an unceasing stream of testimonials. Stephen King has chimed in: “Not just a science fiction writer; a literary icon.” “Always made of fire,” writes fantasy writer Maria Dahvana Headley. “Amazing and unapologetically herself,” says Hugo-winning author Mary Robinette Kowal.

The speaking of her name and of her words goes on, and will go on, today and tomorrow and for a very long time now. As it should. She was the mother of so many of us, and you should take time to mourn your mother.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.