From the Archives: The famous Manson true crime book, ‘Helter Skelter,’ reviewed in 1974

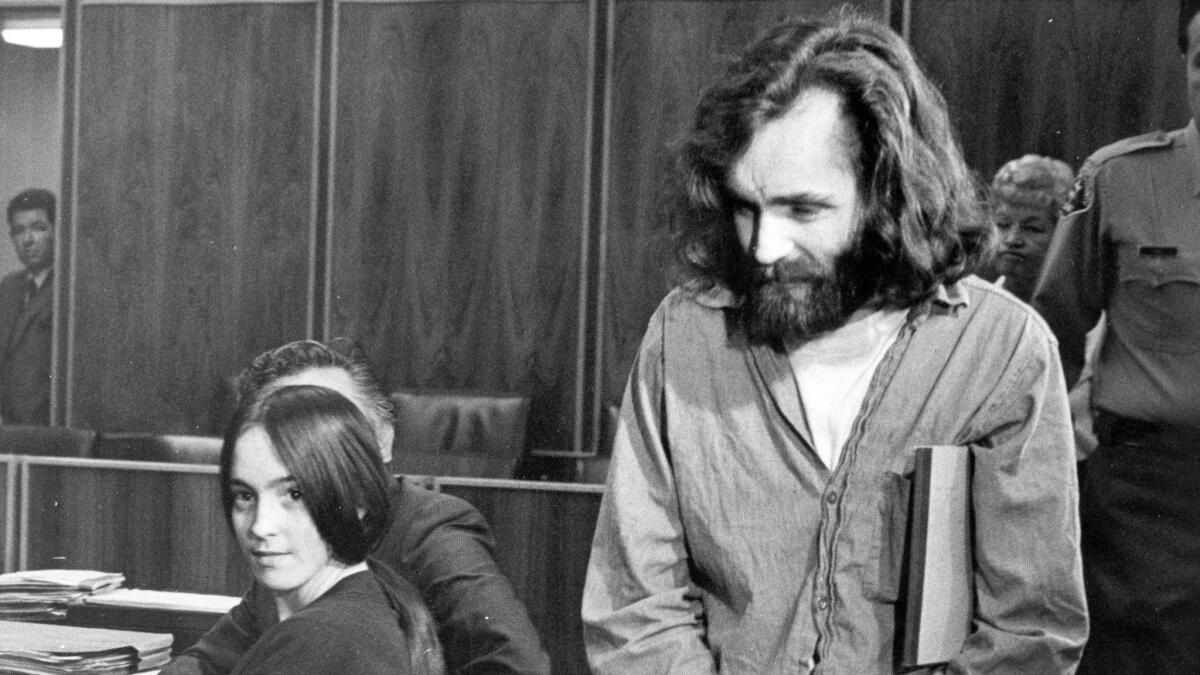

Charles Manson, right, and Manson family member Susan Atkins in court in Santa Monica, 1970.

Charles Manson, 82, was rushed from a Central Valley prison to a hospital this week for an undisclosed medical issue. In 1974, Robert Kirsch, former book editor and critic at The Times, reviewed “Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders,” which has since sold over 7 million copies.

“Occasionally writers refer to a ‘motiveless crime.’ I’ve never encountered such an animal and I’m convinced that none such exists,” Vincent Bugliosi, prosecutor in the Tate-LaBianca trials, says in “Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders.” “It may be unconventional; it may be apparent only to the killer or killers; it may even be largely unconscious — but every crime is committed for a reason. The problem, especially in this case, was finding it.”

The volume, written with the assistance of Curt Gentry, is bound to produce controversy; indeed, the attribution of motive — namely, that the murders were committed to ignite Helter Skelter, Manson’s term for a black-white Armageddon which would end ultimately in power for Manson and his Family — may turn out to be the least controversial aspect of the book. On the course of demythifying this bizarre and brutal case, Bugliosi is highly critical of certain aspects of police performance, of some of the actions of the press, of the probation system, of some judges and attorneys and of individuals who have elevated Manson as a symbolic and even heroic figure.

Bugliosi’s criticisms do not take the form of a blanket indictment. For the most part, he names names, and I am certain that by the time this review appears those who are blamed for ineptitude, or for inadequate performance, will have answered the charges he makes. It is equally certain that ulterior motives will be attributed to Bugliosi: political ambition, promotion of his book and justification of his own work as prosecutor.

Yet none of these certainties is likely to undermine the force and fascination of the work. Though basically a prosecutor’s view of the complex case, the book attempts something more: the most comprehensive account of the murders, the investigation, the trials and the aftermath yet written. Some part of this account emerges from direct observation and months of immersion in the depths of the affair — including the paradoxical nature of the author’s contact with Manson, who often demonstrated his grudging respect for Bugliosi as an adversary by conversing with the prosecutor. It is a measure of the latter’s importance in Manson’s eyes that Bugliosi was put at the top of the Family’s death list.

Idol Speculation

The value of this book lies not only in its revelation of many facets hitherto unreported, or obscured by the succession of developments, but also in the nature of Bugliosi’s unique position in the case. As a prosecutor charged with presenting the evidence in the context of law, Bugliosi did not have the imaginative license granted to other observers. His was a professional task. And while he shared the curiosity and concern of commentators and the public, speculation was a luxury in which he seldom indulged.

It is true that there is speculation in this book — on the possibility that the Manson Family was responsible for as many as 35 or 40 deaths, including those of defense attorney Ronald Hughes and other possible victims, two as late as 1972. There is speculation, also, on the nature of Manson’s techniques of control. But even this is based on evidence gathered by Bugliosi from those who knew Manson, and from his own observation.

One thing is certain: Bugliosi does not buy the mysticism or magic of Charles Manson, nor does he make the common error of identifying Manson and his Family with the penumbra of the occult. His strongest point is common sense. Reminding us of the brutality of the murders, the harsh and ruthless invasion of victim’s homes, he strips Manson of the facile mysteries.

The guru of killing was an enemy of society, a guerrilla on the fringes of civilized life, who discovered, as many have before and since, the fragile vulnerability of individuals in community. Manson was clever and glib, a stir-wise and sophisticated confidence man who exploited the human material and social climate in order to achieve his ends. And his ends included killing. “Death was his trip,” as one former Family member put it.

Bugliosi also reminds us that many stood up to Manson and refused to bow down to his use of fear, to his appeal to deep-seated hostility, to his application of the coded messages of the Beatles’ music or to his selective prophecies of Biblical revelation — the mishmash of new cultic ideas. It took considerable courage for some of his witnesses to testify, for ordinary people to resist the threat of death and come forward, for officials to do their jobs, for society itself to achieve not retribution but justice.

“For there shall arise false Christs, and false prophets,” Bugliosi reminds us in the words of Matthew, “and shall show great signs and wonders; insomuch that, if it were possible, they shall deceive the very elect…Wherefore, if they shall say unto you, Behold, he is in the desert; go not forth…”

In the sensation of the moment, the advice was not heeded. The very enormity of the crimes, the ineptitude of some investigators, the cultural climate of malaise and fear, produced terror and confusion. Some of it still persists; it is painful, even now, to read the details of the crimes, astonishing to see how otherwise sensible and decent people tended to imbue the Mason Family with attributes they never really possessed.

The central point that Bugliosi makes — whether or not one agrees with his specific criticisms or questions Bugliosi’s own motivations — is that fear can becloud judgment. But the overriding obligation of society is to see that the victims did not die in vain. To blinker our view of this bestiality, to gloss over it with vague implications that somehow society itself is to blame, is to abandon the imperative of clear and rational thinking at a time when it is most sorely needed.

This, for me, is the greatest value of the book. To see the law at work in the reality it must cope with — groping, subject to limitations, to the rules of evidence, to the personalities of advocates and judges — is a challenging experience. Whatever the reader’s feelings, the system and some individuals in it compel respect.

Occasionally, weaknesses are revealed. The lack of liaison between and within investigative agencies demands scrutiny. So, too, do the methods of investigation, the reports of pathologists, the taking of physical evidence, the policies that permit the release of sociopaths into the general community, the roles of psychiatry and psychology, the procedures of the courts. Bugliosi raises questions that deserve the most careful attention.

If Bugliosi is critical, he does not hesitate to give credit where he believes it due. And if he is bitter, it is understandable: He resents the attempts to elevate Manson to a folk-hero — this man who was responsible for killing, whose racist ideas are repugnant (he told his followers: “Hitler had the best answer to everything”), who abused the hippie mystique, who debased those around him.

The prosecutor’s case in court is filled out in these pages. He rejects the notion that Manson was a Pied Piper whose source of power is undiscernible: “Those who joined him were not…the typical girl or boy next door… Nearly all had within them a deep-seated hostility toward society and everything it stood for which pre-existed their meeting Manson.” He quotes Dr. Joel Hochman, who testified at the trial that the reasons “lie within the individuals themselves.”

The Family members were Manson’s raw material: “It was a double process of selection. For Manson decided who stayed. Obviously he did not want anyone who he felt would challenge his authority, cause dissension in the group or question his dogma. They chose, and Manson chose, and the result was the Family.”

The “magic,” Bugliosi contends, was and is explicable: Manson sensed and capitalized on the Family’s needs. “I strongly suspect that his ‘magical powers’ were nothing more or less than the ability to utter basic truisms to the right person at the right time,” Bugliosi argues.

Drugs were a tool, but the evidence is that Manson used them sparingly, and that on the nights of the murders the assassins were not under the influence of drugs at all. Sex was another instrument. Both heightened suggestibility. The use of repetition and ceremonials systematically erased inhibitions.

“You can convince anybody of anything,” Manson said in court, “if you just push it at them all of the time. They may not believe it 100%, but they will still draw opinions from it, especially if they have no other information to draw their opinions from.”

Savvy Exploitation

Manson created a climate of isolation. There were no newspapers at Spahn Ranch, no clocks. In that tight little social system, providing what passed as love for the loveless, supplying identity for the confused, playing on fear and alternating threat and acceptance, changing names and leading games, building on the Family members’ sense of alienation. (Dr. Hochman: “I think that historically the easiest way to program someone into murdering is to convince them that they are alien, that they are them and we are us, and that they are different from us.”)

Manson exploited religion and music, Bugliosi points out: “He used his own superior intelligence. He was not only older than his followers, he was brighter, more articulate and savvy, far more clever and insidious. With his prison background, his ever-adaptable line of con, plus a pimp’s knowledge of how to manipulate others, he had little trouble convincing his naïve, impressionable followers that it was not they but society that was sick. This too was what they wanted to hear.”

I do not say that this is the definitive book on the Manson case. But in its detailed, documented and annotated pages, in its description of the way in which the case was investigated and presented, in the background information it provides on the events and persons involved, in its recapitulation of mood and of the actions behind the scenes, it is arguably an indispensable contribution to the necessary dialogue. Certainly it is unique because of the position Bugliosi occupied as a prosecutor.

The fact is that we cannot afford to shrug away the Tate-LaBianca murders: Too much has happened since then to show the threat to society from casual and seemingly senseless violence, from the Santa Crux murders and the Houston mass killings to the crimes of the Symbionese Liberation Army. To accept these as simply symptoms of the malaise of the times is to abandon the obligations of civilization to rationally address even the most irrational and fearful events.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.