Gabriel Garcia Marquez: Five essential reads

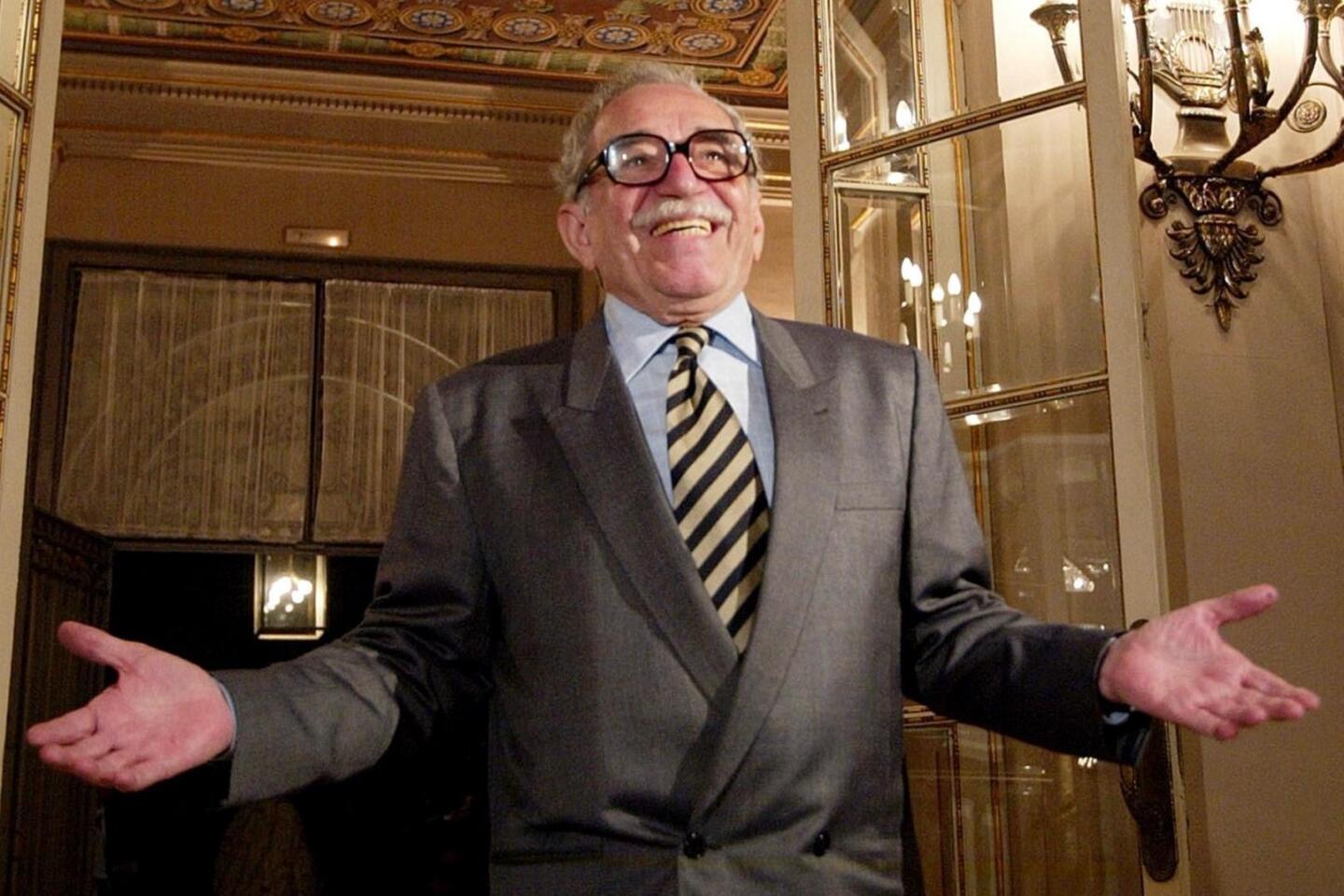

Gabriel García Márquez, who died Thursday at 87, was a prolific writer, dating back to his work as a journalist in the 1950s. I first discovered his books, as so many did, when I was in high school. After having been closed out of a senior seminar that had “One Hundred Years of Solitude” on its reading list, I went out and read the novel anyway -- the one time in all my years of schooling that I ever opened a book for a course in which I wasn’t enrolled.

Over the years, I read most of his work; here are five of my favorites among his books:

“One Hundred Years of Solitude” (1967). “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice,” begins this legendary epic of the Buendía clan and the town of Macondo -- a novel William Kennedy once called “the first piece of literature since the Book of Genesis that should be required reading for the entire human race.”

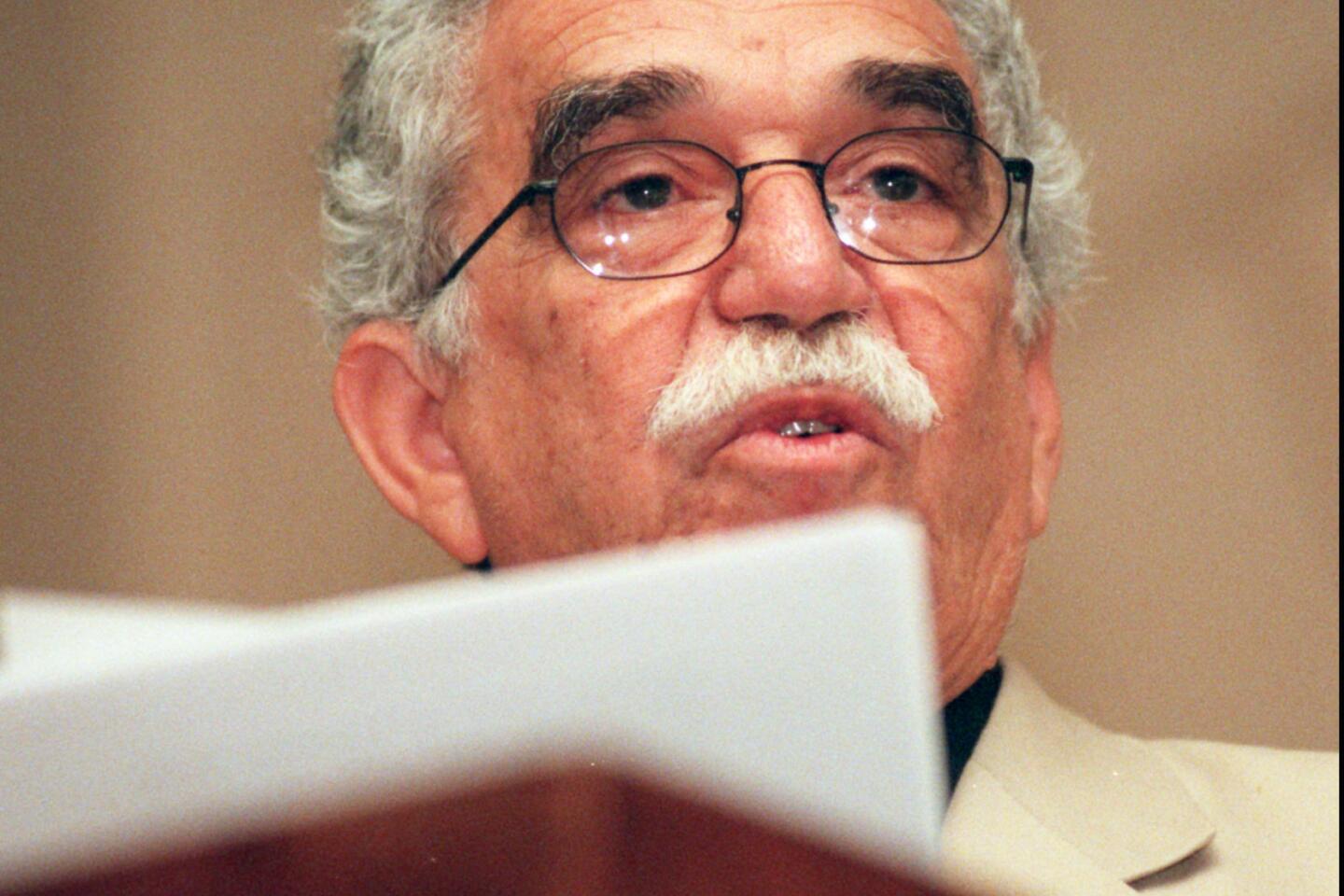

“The Autumn of the Patriarch” (1975). García Márquez called this novel a “poem on the solitude of power” -- the saga of a nameless dictator inspired by Franco and Juan Peron, who sells the very ocean to pay off his country’s debt. “The more power you have,” the author told the Paris Review in 1981, “the harder it is to know who is lying to you and who is not. When you reach absolute power, there is no contact with reality, and that’s the worst kind of solitude there can be.”

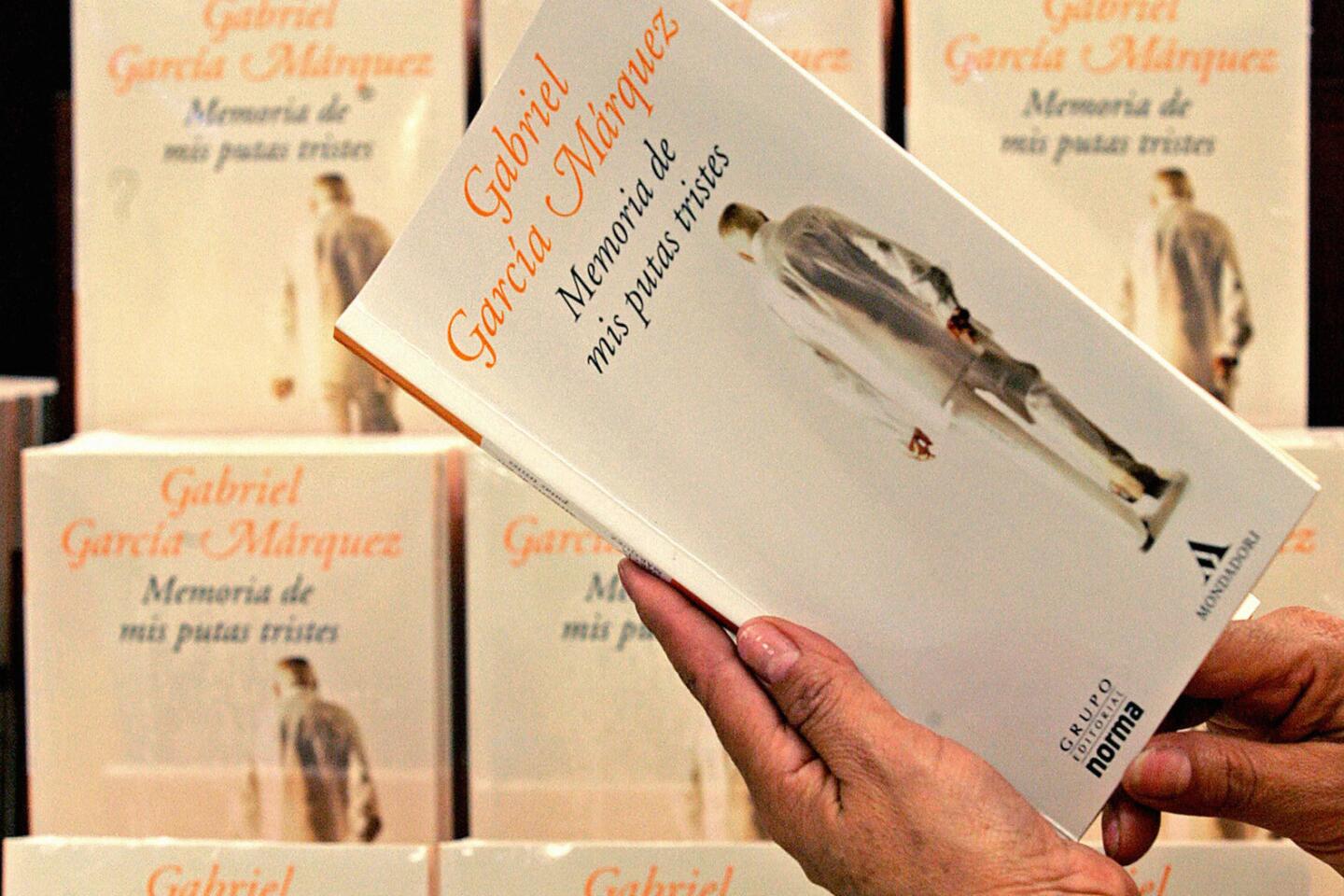

“Collected Stories” (1984). I’m cheating here, because “Collected Stories” is made up of material from three collections -- “No One Writes to the Colonel and Other Stories” (1968), “Leaf Storm and Other Stories” (1972) and “Innocent Eréndira and Other Stories” (1978) -- but why not? The 26 pieces here trace an arc spanning almost a quarter of a century, from early, relatively straightforward efforts to the mature author working at the top of his game.

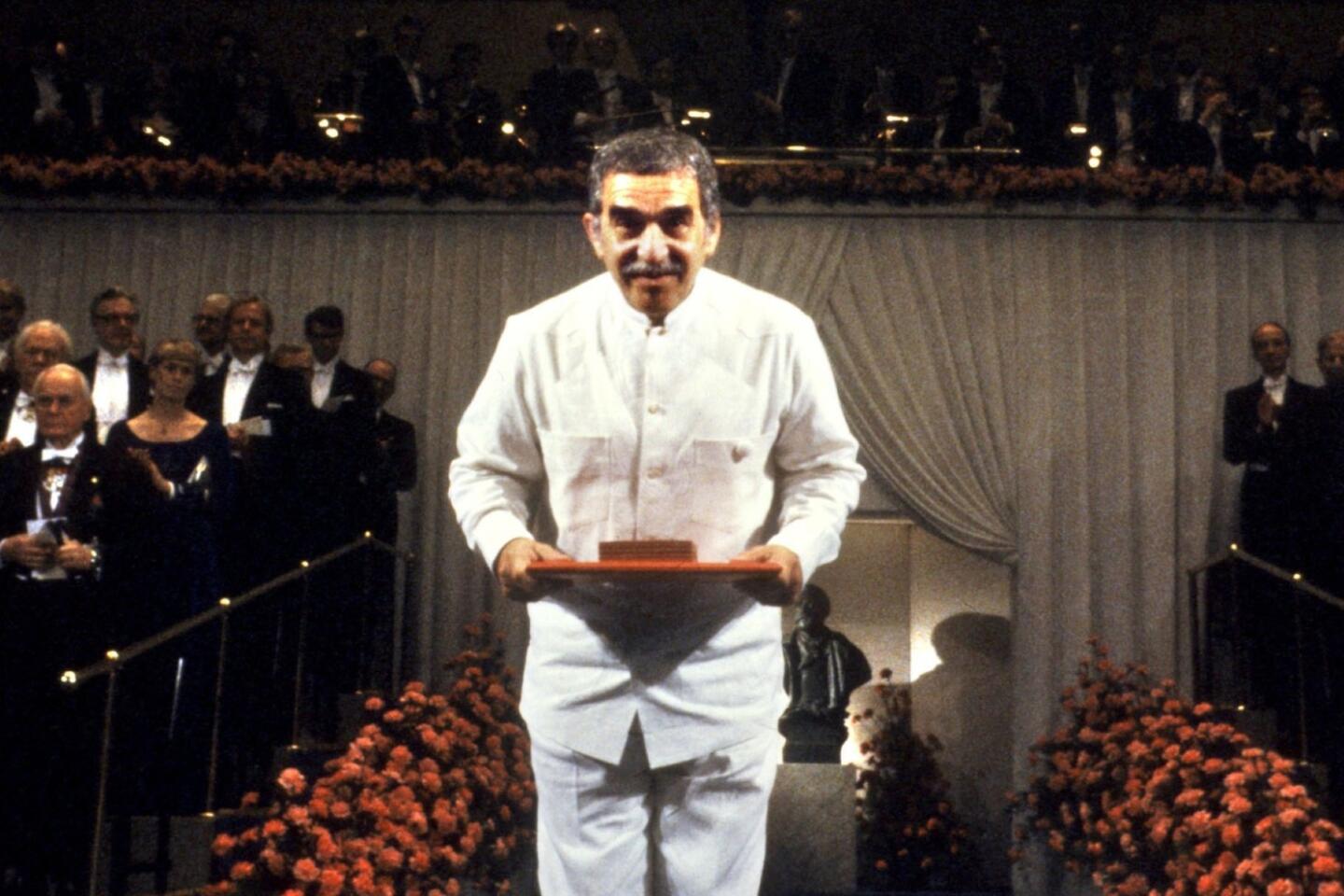

“Love in the Time of Cholera” (1985). The author’s second masterpiece, and his first book as a Nobel laureate, this exquisite novel, based in part on the courtship of his parents, tells the story of youthful love rekindled in old age. “He did not have to keep a running tally, drawing a line for each day on the walls of a cell,” García Márquez writes of Florentino Ariza, who has pined for Fermina Daza for more than half a century, “because not a day had passed that something did not happen to remind him of her.”

“The General in His Labyrinth” (1989). A book that blurs the line between history and fiction, this novel details the last seven months in the life of Simón Bolívar, as he travels from Bogotá to the Caribbean, bound for a European exile he will not live to achieve. “To find probabilities out of real facts is the work of the journalist and the novelist,” García Márquez once said, and here he humanizes Bolívar, portraying him as broken and lost. “Damn it,” he asks, speaking in some sense for all of us, “How will I ever get out of this labyrinth?”

ALSO:

Gabriel Garcia Marquez was more than magical realism

Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Nobel Prize-winning author, dies at 87

The magic of Gabriel Garcia Marquez in Gerald Martin’s biography

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.