For April Fools’ Day, a celebrated literary hoax

The Scottish novelist Alexander Trocchi, who died in 1984 at age 59, was a prime mover in the Paris expatriate scene of the 1950s, founding the literary journal Merlin — the first venue to publish Samuel Beckett in English.

If you’ve never heard of him, though, you’re not alone.

Trocchi essentially gave up writing after the publication of his 1960 novel “Cain’s Book,” and descended into heroin addiction, declaring himself a “cosmonaut of inner space.”

While in Paris, Trocchi cranked out six novels in three years — most of them so-called “dbs” (dirty books) for Maurice Girodias’ Olympia Press. Olympia was one of the legendary publishers of the era, putting out groundbreaking literature (“Lolita,” “Naked Lunch” and “Candy,” to name just a few, were all originally issued by Olympia) in addition to more overtly erotic fare.

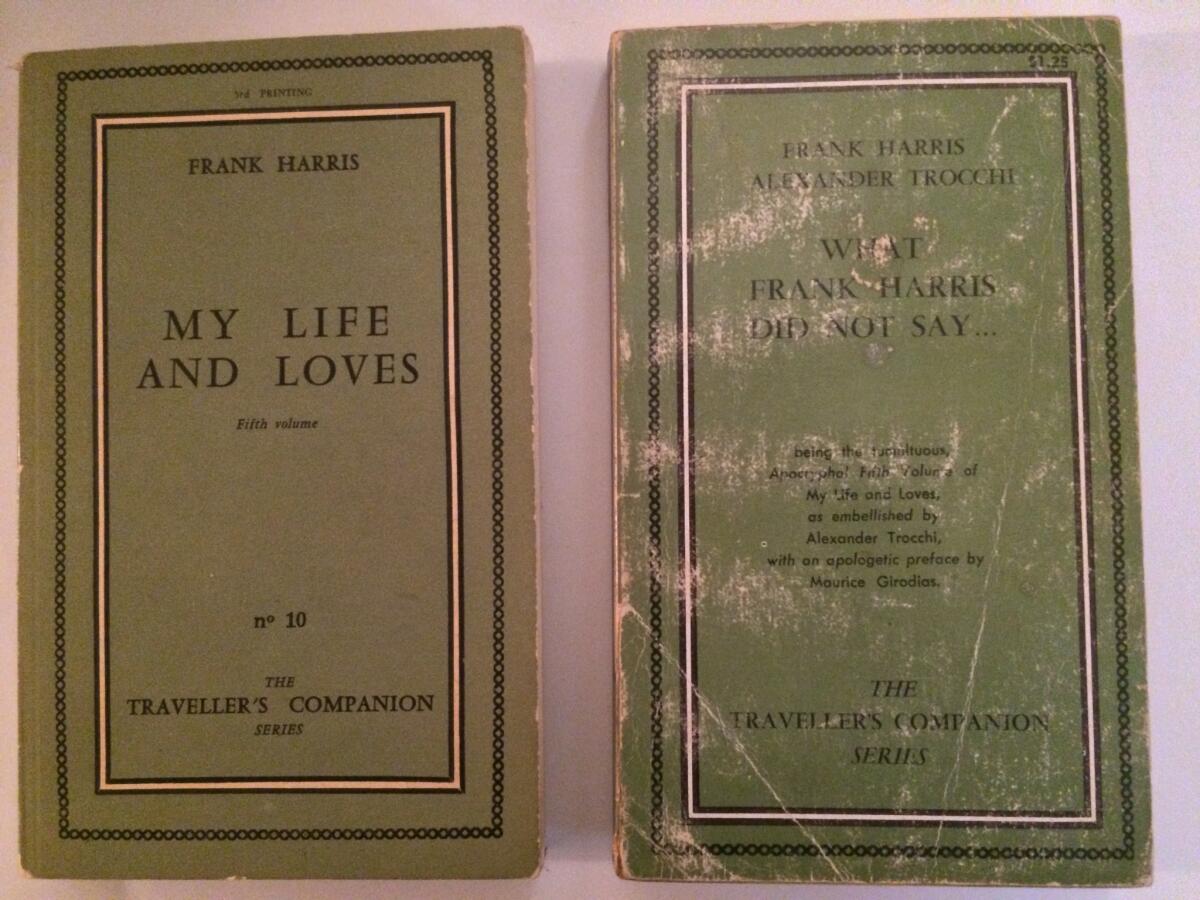

In 1954, Girodias paid a million francs for the rights to a fifth volume of journalist and editor Frank Harris’ explicit memoir “My Life and Loves” — the first four volumes were published in the early 1930s by his father, and banned in the United States and England — only to discover that the work did not exist.

As he learned after making the payment, “[t]he manuscript was made up of a few sheafs of typed pages, yellowed by time; they were drafts of articles written by Harris for various bygone periodicals. He had no doubt put them aside to be incorporated into that projected fifth volume, but he had never gone further into the matter.”

What to do? The solution, Girodias decided, was to enlist Trocchi’s aid. “[C]andidly,” the author would later write, “those pages for which Girodias paid so much were some of the worst writing it has ever been my misfortune to read.”

This, however, didn’t stop him from conspiring with the publisher to make “that fifth volume of Monsieur Frank Harris’s world-famous memoirs … into a really sumptuous work of art.”

Writing feverishly for 10 days and nights, Trocchi turned around the manuscript, which Girodias published under Harris’ name. In his book “Venus Bound: The Erotic Voyage of the Olympia Press and Its Writers,” John de St Jorre asserts that “[s]ome people think Trocchi wrote a better ‘autobiography’ of Frank Harris than Harris himself,” including Harris’ biographer Philippa Pullar.

I’ll be honest: I’ve never had much use for Harris. All that florid Victoriana puts me off. Trocchi, on the other hand, is the real deal, a magnificent and tensile writer who even in his throwaway works never shied away from the abyss.

His “My Life and Loves” reveals the manic intensity of his writing, as well as a subversive wit that heroin later wore away. Not only that, but the Harris hoax fulfilled for him a political agenda — to assault, head-on and at every opportunity, the voices of propriety, the moralists who want to tell us how to live.

If you think that’s an outdated agenda, just look at the Religious Freedom Restoration Act signed into law last week in Indiana, or the similar bill now sitting on the desk of Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson.

These voices never go away, not really, which is why writers such as Trocchi — or even, in his way, Harris — remain essential, offering challenges to the status quo.

Girodias eventually re-issued the fifth volume of “My Life and Loves” as “What Frank Harris Did Not Say…” — with what he called “an apologetic preface.” Is it any surprise that his preface is not apologetic in the least?

No, what this literary hoax embodies is the most gleeful sort of engagement, that of the provocateur.

twitter: @davidulin

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.